Just as when examining the family trees of Judah we found that the descendants of Hezron, grandson of Judah, get by far the most space because it was from that line that David came, so in the case of Levi we find that the most space is given to the descendants of Kohath son of Levi because it was from Kohath that the high-priestly line came.

In dealing with the Kohathites we have to remember that there are two aspects to deal with:

- The priests, who were those members of the tribe of Levi descended from Aaron (Num.3:10, 18:1,7).

- The remainder of the descendants of Kohath, who formed a Kohathite house alongside the other two Levitical houses, the Gershonites and the Merarites. It is worth emphasising that even the descendants of Moses were not priests, but members of the Levitical house of Kohath: “The sons of Amram; Aaron and Moses: and Aaron was separated, that he should sanctify the most holy things, he and his sons for ever, to burn incense before the LORD, to minister unto him, and to bless in his name for ever. Now concerning Moses the man of God, his sons were named of the tribe of Levi” (1 Chron.23:13-14).

At the Time of the Exodus

In later articles, God willing, we shall deal with the priestly line, and the Levitical house of the Kohathites in later times, separately. This article deals with the whole house of Kohath in the era of the Exodus.

The Multiplication of the House of Kohath

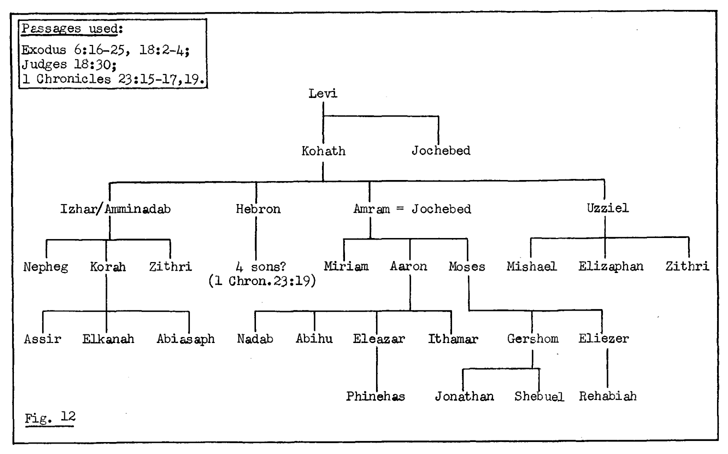

In the genealogy we only have four names, Levi, Kohath, Amram and Moses to cover the period from the entry into Egypt to the Exodus. This is a period of About 200 years, and since Moses was 80 at the time of the Exodus, this is no problem, especially since Levi, Kohath and Amram lived to be 137, 133 and 137 respectively (Ex.6:16-20).

Including Moses and Aaron, there are 12 males of the third generation from Kohath mentioned in the genealogy and a further 9 of the next. Yet the number of males of a month old and upwards of the Kohathites was 8,600 (Num. 3:28) a year after Israel left Egypt (Num.1:1). Many more children, besides those mentioned in the genealogies, must have been born in this family, therefore. Levi is recorded as having 3 sons, Kohath 4 and Amram 2. Yet they would probably have been capable of begetting children for about 100 years each. Bearing in mind that “the children of Israel were fruitful, and increased abundantly, and multiplied” (Ex.1:7), it is reasonable that these men should have had a dozen or more sons, especially if they had more than one wife at once. Whilst Moses was but the fourth generation from Levi, others in this family of 8,600 strong could have been of the tenth generation, for, as 1 Chron. 7:23-27 shows, Joshua was the tenth from Joseph. However, if Levi did have other sons besides Gershon, Kohath and Merari, then they must have been counted in one of the other of the three main tribal families named after these three sons.

It is apparent from the genealogy illustrated, and it is said in Ex.6:20; that Amram married his aunt Jochebed. This does not necessarily mean that Amram married an older woman, however. If Kohath had been born to Levi when Levi was 30, and if Amram had been born to Kohath when Kohath was 30, then Levi ‘would have been 60 when Amram was born. If Jochebed was born to Levi when Levi was 120, then she would have been 60 year younger than Amram, although his aunt! The facts at first suggest to us the picture of a youthful Amram taking his middle-aged aunt to wife. It could just as easily be the case, that Amram took the youthful Jochebed to wife in his old age, having had other wives and children. In fact, the second picture is more likely to be right than the first, for Moses was born at a time when Israel had already multiplied to an extent that Pharaohwas sufficiently worried to want to stop them increasing any more.

We must not think of these earlier genealogies in terms of modern families. The descendants of one man, Jacob, were being multiplied under God’s hand into a nation. The following extracts from an article in the magazine “Time” about the ruling house of Saudi Arabia are interesting in this connection:

“It is the world’s largest royal family; It includes an estimated 5,000 princes, and its female members are, quite literally, uncounted.. .The House of Saud had a powerful revival at the beginning of the 20th century, when its leader was the great Abdul Aziz, generally known as Ibn Saud…Abdul Aziz died in 1953, at about age 73, and has been succeeded by his sons Saud (1953-64), Faisal (1964-75) and the present King Khalid. If Saudi Arabia is underpopulated today, it is not the fault of Abdul Aziz and his descendants. The old lion begat 44 sons and an unknown number of daughters; Saud had 52 sons and 54 daughters. All told, it is estimated that at least 2,000 Saudi princes, including sons, grandsons and great-grandsons, are descended from Abdul Aziz.”

Here we have a man, born 100 years ago, who died at 73 and who has 2,000 male descendants alive today. There is nothing in the least impossible therefore in the rapid growth of the families of Israel in Egypt.

The Kohathites

The Koliathites had the duty of looking after the things relating to the holy place and the most holy place (Num.3:31), presumably because the priests were descendants of Kohath. Whilst the Gershonites and the Merarites had oxen and wagons to carry the heavy items of the rest of the tabernacle, the Kohathites had to carry the items they were responsible for on their shoulders (Num. 7:9). This command was broken when in David’s reign an attempt was made to bring the ark of God into Jerusalem on a cart (1 Chron.13:7). The head of the family at the time of the Exodus was Elizaphan (Num.3:30, spelt Elzaphan in Ex.6:22), the cousin of Moses and Aaron. He and his brother Mishael carried out the unpleasant duty of removing the bodies of Nadab and Abihu when they were struck down by fire from God (Lev.10:4).

The sons of Izhar and Uzziel are supplied in Ex.6:21-22, but no sons of Hebron are supplied in that chapter. 1 Chron.23:19 supplies the names of 4 sons of Hebron, but whether they are actual sons or descendants is another matter, and will be left till we deal with the subsequent history of the Kohathites. At present we have included them in the genealogy with a question mark. Another query arises from 1 Chron.6:22 where the son of Kohath and father of Korah is given as Amminadab, not Izhar. Presumably this is just another name for Izhar.

It is well known that Korah, the cousin of Moses and Aaron, led a rebellion against them. With Aaron and his descendants selected to be the priestly family, and with another cousin, Elizaphan, leading the Kohathite house, he was clearly envious of their God-given authority. As such he is the pattern for the false apostles in the first century who rebelled against the divinely-chosen and inspired true leaders of the church (Jude 11; Core = Korah). The association of Korah with Dathan and Abiram of the tribe of Reuben is readily explicable when it is discovered that the Kohathites pitched on the south side of the tabernacle (Num.3:29) where Reuben also dwelt (Num.2:10-16). Although 250 Levites were actively involved with Korah and were consequently consumed with fire (Num.16:17,35) this did not include his sons, as Num.26:11 specifically points out. They must have recognised that obedience to God comes before even the closest of family ties. Thus the fact that descendants of Korah are mentioned in 1 Chron.6:22-38, and include Samuel and Heman the singer (full details in future articles, God willing), is evidence of the harmony of Scripture, especially when it is noted that it is the families of Dathan and Abiram and not of Korah who are referred to in Num.16:27.

The House of Aaron

Of the four sons of Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, who were struck down by fire, were the oldest and were childless when they died (Num.3:2,4).

Eleazar, the third-born, was in control of the Kohathite branch of the Levites, who were in charge of the sactuary (Num.3:32), whilst his younger brother controlled the other two Levitical families, the Gershonites and the Merarites (Num.4:28,33). Eleazar then became high priest when Aaron died. It is often forgotten that he, as well as Joshua and Caleb, must have left Egypt as an adult and survived the wilderness journey to enter the land. The injunction of Numbers 14 that all would die except Joshua and Caleb did not apply to the Levites, for it is stated in Num.14:29 that it applied to “all that were numbered of you”, and the Levites were not numbered (Num.1:47).

Phinehas, prominent in the later part of the wilderness journey (Num. 25:7, 31:6) was high priest after Eleazar. The mention of him in Jud.20:28 shows that Judges cannot be in chronological order; Judges 17-21, with its appalling incidents, is an appendix to the main book showing the rapid decline of the children of Israel after their good intentions expressed in Joshua 24.

The Family of Moses

Most readers of this magazine might have difficulty in naming the two sons of Moses, so little is recorded of them. Both names could be confused with other people. The eldest was Gershom, not to be confused with Gershon, son of Levi (sometimes called Gershom in 1 Chronicles); the youngest Eliezer, not to be confused with his cousin Eleazar, Aaron’s son.

Nothing is recorded about either of them during the wilderness journey except that they joined Moses at the start (Ex.18:3-4). From Jud.18:30 it would appear that the Levite who became priest in Micah’s house of idolatry was the son of Gershom and grandson of Moses. The AV, following the Hebrew text, has Manasseh; but modern versions, following the Vulgate and Septuagint, prefer Moses, it being generally thought that the Hebrew manuscripts have been altered to avoid the shame of the grandson of Moses being a leader in idolatry. If correct, the reference is another proof of the early date of this part of Judges and further evidence of the rapidity of Israel’s decline after possessing the land.