Introduction

Having established in the first installment of this two-part article that the canonical status of Daniel pre-dates the traditional higher critical date (c. 165 BC), the question that we now have is what length of time we should allocate from the composition of Daniel to its canonical reception.

Textual History

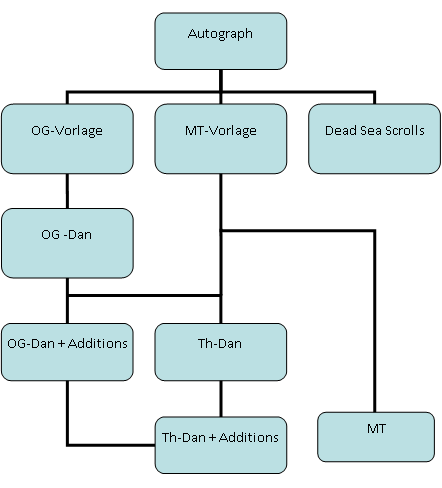

The manuscript evidence from Qumran is not the only method for fixing a terminus ad quem for the book of Daniel. The textual history of the book, primarily its various translations, also provides a method for identifying the footprints of the book. Scholars identify various translations and editions of Daniel and these are shown in Figure 1.

The earliest extant Greek translation (and almost certainly the first) of the book of Daniel is commonly known as the “Septuagint” (LXX) or “Old Greek” (OG-Dan). It is generally accepted that the OG-Dan translator worked from a Semitic Vorlage (source-text, i.e. OG-Vorlage in Figure 1). This Vorlage differed in several important ways from the MT (MT-type text). First, OG-Dan contains longer versions of chs. 4-6 than the MT. Secondly, OG-Dan contains the Apocryphal Additions (Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, the Prayer of the Three Children). The other differences between OG-Dan and the MT, though previous explained by theological bias, are now understood to be due to the OG-Vorlage.[1] OG-Dan is generally dated to the late second century; the Additions, which undoubtedly were composed in Hebrew or Aramaic, predate this translation.

Around the second century AD the Old Greek text of Daniel was replaced in the Christian communities with the so-called “Theodotion” version (Th-Dan), named after its translator.[2] Though ascribed to its eponymous translator, it is almost certain that the text seen in Th-Dan predates Theodotion’s translation of the OT. The reason for this conclusion is that we have citations of Daniel that closely compare with Th-Dan but they pre-date Theodotion.

Figure 1 – The Textual History of the Book of Daniel

A number of scholars regard some NT citations of Daniel as “Theodotionic”,[3] but it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss this question.[4] There are also a number of citations in the apocryphal work Epistle of Baruch.[5] These citations in Baruch are difficult to explain as “independent faithfulness to the Hebrew Daniel 9” and so it is supposed that the text of Daniel witnessed in Th-Dan is older than Baruch.[6]

It is generally recognized that OG-Dan is presupposed by Th-Dan;[7] Di Lella explains Th-Dan as one of several recessions of OG-Dan (inc. “Proto-Lucian”).[8] Th-Dan is frequently closer to the MT than OG-Dan; and significantly, Th-Dan includes short versions of chs 4-6 that are independent from OG-Dan. It is therefore likely that the translator had access to a Hebrew Vorlage, similar to the MT. As P. M. Bogaret concludes, Th-Dan is sometimes a new translation and sometimes a revision of OG-Dan.[9]

Extant copies of Th-Dan contain the Additions, placing Susanna before ch. 1 and Bel and the Dragon after ch. 12. However, it is likely that Th-Dan did not originally contain these additions. Further, Th-Dan translates the divine names differently in the Additions than from the rest of the text, while OG-Dan translates them consistently. Di Lella writes:

This difference proves that originally Th-Dan lacked the supplement in chapter 3 as well as the stories of Susanna, Bel and the Dragon. For these portions Th-Dan provides a recession of OG-Dan based on a substratum that itself is revised. [10]

Th-Dan is generally thought to have originated from Palestine, given its provenance, and so it was likely that the Additions were known in first century Palestinian Judaism.

This information should not lead us to doubt the accuracy of our present versions – as we have seen, the MT is likely to be very close to the Autograph, as confirmed by comparison with the DSS. It is the textual history of the Greek versions that interests us as these recessions imply the passage of years.

Using the citations of Th-Dan in Baruch we can determine a date for Th-Dan. The date of composition of Baruch varies widely from late second century BC to mid-first century AD.[11] Looking at just the known recessions between the Baruch quotations and the Autograph and we can identify at least four time-periods of undetermined length (A-D) that push back the date of the Autograph (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Versions between Autograph and Baruch citations

Period A: Time from composition to OG-Vorlage recession

Period B: Time from OG-Vorlage to OG-Dan translation

Period C: Time from OG-Dan to Th-Dan revision and translation

Period D: Time from Th-Dan to Baruch citations

If we posit a date for Baruch c. 50 AD and if we allow only fifty years for each recession stage and then a composition of the Autograph, c. 165 BC might be plausible. However, we have good reason for considering fifty years to be overly optimistic. If the author of Baruch is using Th-Dan as an accepted translation of the OT then this implies that this translation was not only known but received. Similarly, if the existence of Th-Dan implies that OG-Dan was well-known and widely received, but also widely deemed to be substandard – all this takes time. If we allow an only slightly more generous seventy-five years for each recession stage then a composition of the Autograph c.165 BC is impossible. Equally, if the date of composition for Baruch can be shown to be earlier than c.50 AD then a composition of the Autograph c.165 BC is impossible.

Conclusion: Comparable Baruch quotations fix a terminus ad quem of c.50 AD for Th-Dan

Literary References

Another way of identifying a terminus ad quem for the composition of Daniel is to identify comparable quotations and allusions in other texts, assuming they can be dated with a degree of certainty. We have already noted that Daniel is cited frequently in the NT and other Christian writers. It has sometimes been asserted that Daniel could not have been written in the sixth century because it is not referred to in Jewish works until the first century. It is, however, important to point out that we do not have copies of many Jewish works written between the fifth and second centuries, so even if this were true, it would not be a particularly strong argument against the early date. In fact, we will see that literary references that can be found in Jewish works attest to the wide popularity of the book of Daniel and make a second century date improbable.

Dead Sea Scrolls

Eight incomplete manuscripts of the book of Daniel have been discovered at Qumran, the earliest dating from c. 125 BC.[12] It is likely that each manuscript originally contained the complete book, except 4QDane which may have contained only the prayer of chapter 9.[13] All twelve chapters are attested, though not in full; none of the Additions are attested. The three manuscript containing chapters 4-6 witness to the shorter versions found in the MT.[14] The distribution of Hebrew and Aramaic matches that preserved in the MT. The text at Qumran is largely consistent with the MT and there are few significant textual variants, although E. Ulrich notes that “the OG frequently agrees with the Qumran reading against the MT”.[15]

As well as the eight Daniel manuscripts found at Qumran, there were also discovered several other manuscripts that refer to the book of Daniel or that are based upon its stories.

- The War Scroll (c. 50 BC – 50 AD). Several copies of the War Scroll were found at Qumran, both in cave 1 (1QM, 1Q33) and in cave 4 (4Q471, 4Q491-7), which demonstrates how popular this document was. The text itself describes the final battle against the Gentiles, particularly the Kittim, and also contains many rules about military preparation and conduct. The War Scroll makes many allusions to the book of Daniel. G. Vermes presents the thesis that this work drew its inspiration from Dan 11:40-12:3, the final battle, and was later expanded with other material.[16] Vermes also refers to the fact that the several manuscripts of the War Scroll found at Qumran differ from one another. This shows that there wasn’t a single version of the War Scroll. Over time changes had been made leading to the existence of several different redactions or versions.

- Florilegium (4Q174). This text dates from c. 25 BC.[17] It is a midrash about the Last Days. It writes of these times saying:

This is the time of which it is written in the book of Daniel the Prophet: ‘But the wicked shall do wickedly and shall not understand, but the righteous shall purify themselves and make themselves white’. The people who know God shall be strong.[18]

- Pseudo-Daniel in Aramaic (4Q243-5). This is collection of three small fragments seem to be based upon the Daniel story.

- The Four Kingdoms (4Q552-3). This Aramaic work is based upon the vision of Daniel 7. Here the four kingdoms are not represented by beasts but by trees.

- Aramaic Apocalypse (4Q246). A particularly significant text based upon the visions of Daniel 7. What makes this text so interesting is that it uses the words “son of God”, though it is not clear whether this figure is meant to be a saviour or a blasphemous tyrant.

- 4Q551 or 4QDanSus. This is very fragmentary text and is therefore difficult to interpret. It is probably not part of the apocryphal Susanna story preserved in the Septuagint. It may be based upon that story or may be an antecedent of the Susanna story.

- Melchizedek (11Q13). This text (c. 50 BC) is about a heavenly saviour identified as Melchizedek who is to come and proclaim freedom for the captives in the Last Days. He is described as “the Anointed one of the spirit, concerning whom Dan[iel] said …”. Though the text is damaged, it is likely that it refers to Dan 9:25.

The eight manuscripts of the book of Daniel attested to the popularity of the book with the Essenes living at Qumran between the second century BC and the first century AD. These manuscripts give us broader picture. The quotations in Melchizedek and Florilegium show that by the first century BC (at the latest) the Essenes regarded the book of Daniel as Scripture. By the first century AD the Essenes had created new stories and commentaries based upon Daniel, including several redactions of the War Scroll. The idea that the Essenes only read the book of Daniel for the first time in mid second century is made improbable by the wealth of literature they would then have produced in such a short space of time.

Second Century BC

The texts found at Qumran are not the only texts from this period that refer to the book of Daniel. The first book of Maccabees quotes explicitly from Daniel when it says:

Now the fifteenth day of the month Casleu, in the hundred and forty fifth year, they set up the ‘abomination of desolation’ upon the altar, and built idol altars throughout the cities of Judah.[19]

And again:

Daniel for his innocence was delivered from the mouth of lions.[20]

Scholars generally agree that I Maccabees was written around 100 BC. The last recorded event is when John Hyrcanus becomes king, which took place 134 BC, and so it is likely that I Maccabees was composed shortly after this date.

As already noted, OG-Dan (and Th-Dan) includes three additions to the book of Daniel not included in the Hebrew version, or amongst any of the manuscripts found at Qumran. These are called the Prayer of Azariah (sometimes called The Song of the Three Children), Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon. These stories are generally recognized to be additions to Daniel, not only because they are not found in the MT (or DSS) but also because they are inconsistent with the rest of the book and their addition disrupts the order of the other material. Scholarly consensus dates these additions before 100 BC, the approximate date of their translation into Greek in OG-Dan. Some scholars have looked for references to the crisis preceding the Maccabean revolt in these additions,[21] which would imply a date for these additions contemporary with the proposed date for Daniel itself.

In Baruch, the author refers to Nebuchadnezzar and Belshazzar as being father and son and as living at the same time. This historical inaccuracy is probably based upon a misunderstanding of Daniel 5, which is sometimes taken to imply that Nebuchadnezzar was the biological father of Belshazzar. There is no consensus regarding the date of Baruch, though many scholars date it to the first century BC on the assumption that Daniel was composed in the second century. Were Daniel not dated so late then Baruch could be dated earlier.

Conclusion: Citations and allusions in Jewish literature fix a terminus ad quem of late second century BC for the book of Daniel

Third/Fourth Century BC

One tantalizing piece of evidence from Qumran is the fragments that have been found of the book of Enoch. One of these fragments, “Astronomical Enoch” (4Q208), has been carbon-dated to 186-92 BC.[22] Given 4Q208 has been dated paleographically to around 200 BC, these two methods agree on an early second century for this fragment.

What makes this fragment so significant is that the Ethiopic book of Enoch contains a lot of material that alludes to the book of Daniel, particularly its use of the imagery of “the Son of Man” (Dan 7:13). In this form, the book of Enoch must have been completed after the book of Daniel, and so if the fragments discovered at Qumran attested to this form then this would provide decisive evidence against the second century date for the book of Daniel.

Unfortunately the fragments discovered at Qumran make up only a small amount of the text of the book of Enoch and many of the fragments are too small for translation.[23] The fragments do not contain any of the Son of Man material, while the Astronomical sections are much longer at Qumran than in the Ethiopic. Scholars speculate that the book, though perhaps originally composed as early as 400 BC, underwent several revisions over its history and did not take its final form until after the completion of the New Testament.[24]

Conclusion: If discovered, allusions in Qumran Enoch would fix a terminus ad quem of early second century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

Fifth Century BC

The book of Nehemiah was written towards the end of the fifth century BC. Nehemiah is an exile in court of the Persian king Artaxerxes. Distressed by news from Jerusalem of those Jews who have returned, Nehemiah prays to God. H. A. Whittaker observes regarding this chapter:

When Nehemiah prayed for the peace of Jerusalem, he closely modeled his prayer on that of Daniel, so presumably he already had a copy of the Book of Daniel included in his Bible![25]

Comparison of the two prayers demonstrates their connection:

And I said, ‘O LORD God of heaven, the great and awesome God who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those who love him and keep his commandments …’ Neh 1:5 (ESV)

And I prayed to the LORD my God, and made confession, and said, ‘O Lord, great and awesome God, who keeps covenant and steadfast love with those who love him and keep his commandments …’ Dan 9:4 (ESV)

Both men confess their sin and the sins of the nation of Israel. Both men refer to the curses laid down in the Law of Moses. And both men pray for the restoration of the nation of Israel.

Nehemiah did not copy his prayer word for word from Daniel; he tailored it to his own situation. His prayer is also shorter than Daniel’s, which probably indicates that Daniel’s is the original. However it is possible that both men based their prayers upon a traditional prayer-format, which may explain their similarities.

Conclusion: Parallels in Nehemiah may indicate a terminus ad quem of late fifth century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

Sixth Century BC

The prophet Zechariah was one of the Jews who returned to Jerusalem after the exile with Zerubbabel to rebuild the Temple.[26] In the book named after him there are recorded the account of a series of visions which Zechariah received. One of these is clearly based upon Daniel’s vision of the four beasts.

And I lifted my eyes and saw, and behold, four horns! And I said to the angel who talked with me, ‘What are these?’ And he said to me, ‘These are the horns that have scattered Judah, Israel, and Jerusalem”. Then the LORD showed me four craftsmen. And I said, ‘What are these coming to do?’ He said, ‘These are the horns that scattered Judah, so that no one raised his head. And these have come to terrify them, to cast down the horns of the nations who lifted up their horns against the land of Judah to scatter it’. Zech 1:18-21 (ESV)

As in Daniel’s vision, and the Four Kingdoms from Qumran, here we have a series of four kingdoms of the Gentiles. The use of horns as a symbol of kingdoms is the equivalent to the use of this symbol in Daniel.

Conclusion: Parallels in Zechariah may indicate a terminus ad quem of late sixth century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

Summary and Findings

In this two-part study we have aimed to identify fixed points (terminus ad quem) from which to calculate the latest possible date for the composition of the book of Daniel. We have identified at least two fixed points that provide a terminus ad quem for the book itself:

Position 1: 4QDanc fixes a terminus ad quem of 125 BC for the book of Daniel

Position 2: Citations and allusions in Jewish literature fix a terminus ad quem of late second century BC for the book of Daniel

Both these fixed points presuppose the canonical reception of the book of Daniel and implies the following time-period:

Period X: Time from composition to canonical reception

Therefore we can define the calculation for the latest possible date for the composition of book of Daniel as follows:

(Position 1 or Position 2) – (Period X) = the latest possible date

In other words, if Period X is longer than forty years then the late date (165 BC) for the composition of the book of Daniel is impossible.

We have also identified a fixed point that provides a terminus ad quem for a Greek translation of Daniel:

Position 3: Baruch citations fix a terminus ad quem of c.50 AD for Th-Dan

As we have seen, this date presupposes four time periods between the recessions that led to Th-Dan translation of Daniel:

Period A: Time from composition to OG-Vorlage recession

Period B: Time from OG-Vorlage to OG-Dan translation

Period C: Time from OG-Dan to Th-Dan revision and translation

Period D: Time from Th-Dan to Baruch citations

Therefore we can define a second calculation for the latest possible date for the composition of the book of Daniel as follows:

(Position 3) – (Period A) – (Period B) – (Period C) – (Period D) = the latest possible date

If these four periods were longer than an average of 52.5 years then the late date (165 BC) for the composition of the book of Daniel is impossible.

We have also identified three tentative terminus ad quem any one of which, if confirmed, would necessarily rule out the late date.

Position 4: If discovered, allusions in Qumran Enoch would fix a terminus ad quem of early second century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

Position 5: Parallels in Nehemiah may indicate a terminus ad quem of late fifth century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

Position 6: Parallels in Zechariah may indicate a terminus ad quem of late sixth century BC for the book of Daniel (tentative)

It is hoped that future research will identify a sound methodology upon which to calculate the probably length of Periods A-D and Period X, which would provide definitive proof against the late date hypothesis and force critical scholars to consider the historical and linguistic evidence upon which the early date is established.

[1] A. A. Di Lella, “The Textual History of Septuagint-Daniel and Theodotion-Daniel” in The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception (2 vols; eds. J. J. Collins & P. W. Flint; Leiden: Brill, 2001), 2:592.

[2] J. A. Montgomery, The International Critical Commentary: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Daniel (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1927), 26-7.

[3] See J. J. Collins, Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 9n; Di Lella, The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception, 593.

[4] [Ed. AP]: For an introduction to this whole area, and a discussion that is corrective of scholarship (albeit with a different example text), see J. W. Adey, “Is Hebrews 10:5’s ‘body’ language from the Septuagint?”, Christadelphian EJournal of Biblical Interpretation Annual 2007 (Sunderland: Willow Publications), 204-228.

[5] Bar 2:11 / Dan 9:15; Bar 1:15-16 / Dan 9:7-8; Bar 2:14 / Dan 9:17; F. Watson, Paul and the Hermeneutics of Faith (London: Continuum, 2004), 457n74.

[6] Watson, Paul, 457n74. For an opposing view, see E. Tov, The Greek and Hebrew Bible (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 519ff.

[7] Collins, Daniel: A Commentary on the Book of Daniel, 8.

[8] Di Lella, The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception, 595-6.

[9] P. M. Bogaert, “Relecture et refonte historicisante du livre de Daniel attestées par la première version grecque (Papyrus 967)” in Études sur le judaïsme hellénistique, (eds. R. Kuntzmann & J. Schlossar; LD 119; Paris: Les Editions du Cerf, 1984), 197-224.

[10] Di Lella, The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception, 599.

[11] J. E. Wright, Baruch ben Neriah (Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2003), 47; A. Salvesen, “Baruch”, The Oxford Bible Commentary (Oxford University Press, 2001), 699.

[12] E. Ulrich, ““Daniel Manuscript from Qumran. Part 1: Preliminary Editions of 4QDanb and 4QDanc”“ BASOR 268 (1989): 17-37; cf. E. Ulrich, “Daniel Manuscript from Qumran. Part 2: Preliminary Editions of 4QDanb and 4QDanc”, BASOR 274 (1989): 3-26.

[13] M. Abegg Jr., P. Flint & E. Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1999), 482-3. This is not the only instance from Qumran where biblical prayers were copied out apart from their source-text. It is likely that these prayers were used for liturgical purposes.

[14] 4QDana, 4QDanb, 4QDand.

[15] E. Ulrich, ‘The Text of Daniel in the Qumran Scrolls’ in The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception (2 vols; eds. J. J. Collins & P. W. Flint; Leiden: Brill, 2001), 2:573-585 (580).

[16] G. Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (London: Penguin Books, 2004), 164.

[17] Abegg Flint & Ulrich, Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, 484.

[18] 4Q174.II; cf. Dan 12:10.

[19] I Macc 1:54; cp. Dan 12:11

[20] I Macc 2:60; cp. Daniel 6

[21] e.g. “you did deliver us into the hands of lawless enemies, most hateful forsakes of God, and to an unjust king, and the most wicked in all the world” (Prayer of Azariah .9)

[22] A. J. T. Jull, “Radiocarbon Dating of the Scrolls and Linen Fragments from the Judean Desert”, Radiocarbon 37:1 (1995): 11-19 (14).

[23] Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English, 545.

[24] Abegg Flint & Ulrich, Dead Sea Scrolls Bible, 481.

[25] H. A. Whittaker, Exploring the Bible (Wigan: Biblia, 1992), 34, (original emphasis).

[26] Ezra 5:1