Introduction

The standard conservative introduction to the topic of dating the Hebrew kings is E. R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings.[1] Modifications of Thiele’s chronology have been made by other conservative scholars, for example by R. K. Harrison in his Old Testament Introduction.[2] Harrison respects the Hoshea synchronism of 2 Kgs 18:1-2 in which Hezekiah “became king” in the third year of Hoshea (729-728); Thiele had regarded this synchronism as an editorial corruption. As Harrison observes, this synchronism can be harmonised when it is recognised that Hezekiah and Ahaz were co-regent for a period of time. J. B. Payne’s comment on Thiele is that “Thiele’s refusal to recognize any synchronism between the reigns of Hoshea and Hezekiah, or to grant any form of accession prior to 715 B.C., has undergone widespread criticism”.[3] Those that have criticized Thiele have sought to maintain the complete accuracy of the biblical record.

Another difficulty with Thiele’s chronology, which remains uncorrected, surrounds Menahem whose reign is given by him as 752-742. This has been challenged by scholars who point to records in the Assyrian annals and building inscriptions, which have Menahem paying tribute to Tiglath-Pileser in 738. The annals of Tiglath-Pileser and his building inscriptions[4] are fragmentary and scholars have disagreed in the past on how to correlate the accounts to Tiglath-Pileser’s campaign years as delineated in the Assyrian Eponym List.[5] Nevertheless, there is some consensus for what they can contribute to an understanding of biblical chronology, and against Thiele, the consensus view is that Menahem possessed a throne in Israel in 738.

There are then two widely accepted criticisms of Thiele and in this article we will discuss further the chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah.

Chronological Principles

If a scholar is ready to accept errors in the biblical record, s/he may configure the chronology of Menahem, Hezekiah and Hoshea in any number of ways.[6] If a scholar seeks to maintain the accuracy of the biblical record, s/he needs to explain why the chronological data is presented as it is and should not be read in a straightforward sequential manner.

Thiele divides his treatment of the Kings chronology into two parts—early kings up to 841 and later kings after 841.[7] If the years of the various later kings of Israel and Judah are added together, using a common starting point of the reign of Jehu and Athaliah in 841, then by the end of the Northern Kingdom, the totals do not match and the synchronisms between the various reigns get out of alignment; a similar point can be made in respect of the early kings. The virtue of Thiele’s treatment is that he describes some of the components of any harmonic reading of the data. An enhanced statement of some of his variables is as follows:

- The historical records of both Israel and Judah have been included in Chronicles and Kings and therefore they are mixed up and a reader needs to be aware of the chronological scheme he is reading at any point.[8]

- Scribes may count the total number of years for a king from the part year in which he ascended the throne or beginning with the first complete “accession” year of his reign. Scribes in Northern Israel may have worked a different system to those in Judah and at different times in the history of the dual monarchy.[9]

- Scribes may or may not include the year in which the king died in his total number of years.[10] This may be determined by how close the king’s death was to the beginning of a year. Likewise, they may have not included part years at the beginning of a reign if the time-period was as trivial as a few weeks.

- Co-regencies existed among some fathers and sons giving rise to overlapping “reigns”, but the total number of years for a king’s reign may or may not include any co-regency element depending on whether the son was “ruling” as king alongside his father.

- Coups, counter-coups, and rival kings in Northern Israel impact the chronological counter. Scribes for a new dynasty may or may not have followed any precedent set by the scribes of former monarchs.

- Northern Israel starts the year in the spring (Nisan) and Judah in the autumn (Tishri);[11] scribes of north and south may have synchronized reigns between the kingdoms upon either basis.

The start dates and lengths of reign for the kings can be set up in a spreadsheet with cells divided into units of 12 months and start and end dates can be moved to bring about a harmonic reading of the reigns of the two monarchies.[12] The variable factors listed above mean that adjustments can be plus or minus a year or two at each changeover of a king. Such adjustments can accumulate or be self-cancelling but the synchronisms between the two monarchies and the absolute Assyrian dates serve as a control upon the process. Hence, Thiele’s principles will inevitable produce slightly variant chronologies on the part of conservative scholars. It would take a series of articles to discuss the Dual Monarchy and its chronology; here we will take two examples, one straightforward and one difficult:

(1)

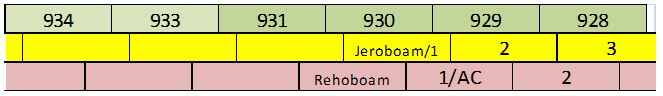

In the above diagram, Rehoboam comes to the throne in 930 but the years of his reign are totaled from Tishri-Tishri (930-929)—the first complete year of accession. Jeroboam’s rebellion was in 930 but as a partial coup, scribes count his years from his “declaration of independence”, allowing the total years of his reign to be calculated from Nisan 930. Judah uses the method of discounting the part years of the new kings opening year. Such an assumption is more reasonable for Rehoboam as he was the legitimate successor to Solomon and scribes might reasonably be expected to follow any chronological scheme of the Solomonic kingdom. With Jeroboam the situation is different as his new kingdom adopted the alternative system of counting part years—he was not a successor to Solomon. If his rebellion was not cemented until further into 930 and a declaration of independence made later, the total number of his years would be counted from Nisan 929, which would place the end of his reign on by a factor of 1.

The decision here affects synchronisms. Abijah will come to the throne in Jeroboam’s 18th year (1 Kgs 15:1) and Asa in Jeroboam’s 20th year (1 Kgs 15:9). If Jeroboam’s “starting year” is out by a factor plus or minus 1, the synchronisms will be “out”.

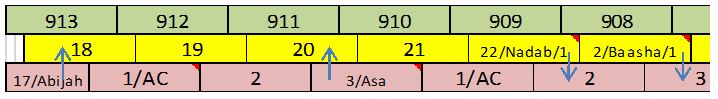

In the above diagram, we have moved on in the process and it illustrates a number of choices. First, Rehoboam, who ruled for 17 years (1 Kgs 14:21), dies in 913 rather than 912. Secondly, Abijah succeeds but his total number of years is calculated from his first complete year, the “accession” year. Thirdly, the same assumption is made for Abijah as for Rehoboam—he died in his third year, which is accredited to him in full. Thus Asa’s first year is counted from his accession year.

These decisions cohere with the synchronisms in the text: Abijah is said to begin his reign in the 18th year of Jeroboam and Asa in the 20th year of Jeroboam. In both cases this synchronism is with their ascent to the throne—their first part-year, rather than with their official “accession” year. With these choices the synchronisms of Nadab and Baasha also fall into place: Nadab ascended the throne in the 2nd year of Asa (with Jeroboam dying in his 22nd year) and Baasha slew Nadab in the 3rd year of Asa.

(2)

The second example is more complicated and further on in the synchronized chronology of the kings of Israel and Judah. Broadly speaking, Thiele’s chronology works give or take a year or two either way until Ahaz and Hezekiah; it is here that he goes wrong. Discussion of Ahaz illustrates a different principle than that of our first example; this principle concerns the difference between contemporary source-records from Northern Israel and from Judah and their different accounting of start dates and totals for their respective kings.

The introduction of Ahaz is as follows:

Twenty years old was Ahaz when he began to reign, and reigned sixteen years in Jerusalem, and did not that which was right in the sight of the Lord his God, like David his father. 2 Kings 16:2 (KJV)

This text reads as if Ahaz began to reign at 20 and reigned thereafter for 16 years and ceased to reign at 36. However, the common Hebrew for “to reign” also does duty for “become king”; thus an equally valid translation is,

2 Kgs 16:2

Akêl.m’B. zx’äa’ ‘hn”v’ ~yrIÜf.[,-!B,

Son of twenty years, Ahaz, when he became king

This text uses a Qal infinitive (Akêl.m’B.) with a preposition and an unexceptionable translation would be “when he became king”.[13] The same phraseology is used in the case of Jehoash:

2 Kgs 11:21

Ak)l.m’B. va’îAhy> ~ynIßv’ [b;v,î-!B,

Son of seven years, Jehoash, when he became king

In the case of Jehoash, it is reasonable to suppose that Jehoiada the High Priest ruled while Jehoash was a child. In the same way, it is reasonable to propose that “becoming” king does not necessarily mean that an individual has assumed the sole reign of kingship; sons could be anointed king prior to the demise of their fathers; sons could exercise power (or not) in place of their fathers; an example of this would be Jotham’s rule in place of Uzziah (2 Chron 26:21).

Was Ahaz anointed king at the age of 20 but without assuming the mantle of power? The synchronisms between Ahaz and the kings of Northern Israel require such a co-regency. The evidence is as follows:

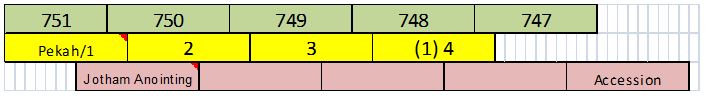

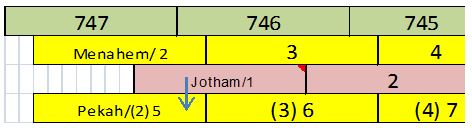

1) Jotham reigned for 16 years (2 Kgs 15:33) but the record knows of a 20th year of Jotham (2 Kgs 15:30). This “discrepancy” is explained by observing that the reference to a 20th year comes in a record fragment about Pekah and his demise at the hands of Hoshea;[14] it is a record written from the perspective of Northern Israel and narrates events in the history of the northern tribes. The “20 years” have a basis in the historical sources from Northern Israel and the most likely hypothesis is that the base year for northern scribes is Jotham’s anointing as king rather than his accession to the throne as a sole ruler. This is illustrated below:

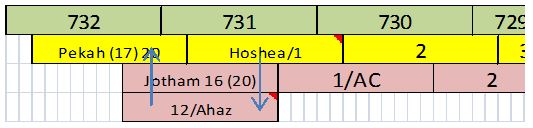

2) A similar distinction applies to the data about Ahaz. Hoshea came to power in the 12th year of Ahaz (2 Kgs 17:1), but this remark is in a record fragment about Northern Israel and embedded with other records from Northern Israel; the base year for calculating the 12th year is likewise Ahaz’ anointing as king; it is not a calculation based on his year of accession as sole king.

This is proven by the fact that Ahaz assumed the throne as sole ruler in the 17th year of Pekah (2 Kgs 15:30; 16:1). A sequential reading of the data produces inconsistency because this requires the record to say that Hoshea came to power much earlier in Ahaz’ reign, and on a sequential reading in his third or fourth year. However, a sequential reading makes the mistake of not respecting the independence of records about Northern Israel and Judah. The base year for calculating Ahaz’ 12th year is not the year in which he assumed the throne but the year in which he was anointed king. This is illustrated below:

The diagram shows that Ahaz assumed the throne in 732-731. The Northern Israel record has this as his 12th year which would place his anointing in 744-743. The year 732-731 is 20th year of Jotham from the point of view of Northern Israel and this is also the year in which the commencement of Hoshea’s reign is noted (2 Kgs 15:30).

3) The final argument for our reading concerns Pekah. Ahaz begins his reign in the 17th year of Pekah, but this begs the question: is this year 17 out of the 20 which we have recorded for Pekah? The note about the 17th year comes in a record about Ahaz and gives the Judean perspective. The detail about Pekah having 20 years comes in a record about events in Northern Israel (2 Kgs 15:27) and we cannot simply assume the same base year. The text states,

In the two and fiftieth year of Azariah king of Judah Pekah the son of Remaliah began to reign over Israel in Samaria: twenty years. 2 Kgs 15:27 (KJV revised)

We have revised the KJV to reflect the Hebrew which states that Pekah began to reign in the 52nd year of Uzziah and notes a period of 20 years without stating Pekah reigned 20 years.

Thiele has shown how Pekah and Menahem were rival kings in Northern Israel.[15] This situation raises the question as to when a king becomes a king—which king did Judah “recognise”? In the records about Judah’s kings, Jotham and Ahaz, the 2nd and 17th years are noted and the two notes pivot around the beginning and end of Jotham’s 16 year reign. This suggests that Judah recognised Pekah as a king in Israel in 747-746. This is illustrated below:

Jotham began his reign in 747-746 which was the 2nd year of Pekah from the point of view of the scribes keeping the records in Judah. However, from the point of view of Pekah’s own record-keepers, this was the fifth year of his assumption of power.

The points (1)-(3) above show that mistakes in interpreting the chronological data of the kings of the Dual Monarchy arise because it is not sufficiently recognized that the records are comprised of different contemporary source materials written from the perspective of Judah in the south and Israel in the north.

Conclusion

It is uncontroversial to propose that the Book of Kings was written over time as contemporary records were added to the ongoing history of the kings of Israel and Judah. It is surprising that there is not a single dating scheme in place for all events; the dating schemes of different source materials have been preserved intact. The integrity of the original inspired source has been respected.

[1] E. R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (New Revised Edition; Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 1983).

[2] R. K. Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament (Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1970), 188-190.

[3] J. B. Payne, “The Relationship of the Reign of Ahaz to the Accession of Hezekiah” Bibliotheca Sacra 126 (1969): 40-52 (40).

[4] The standard edition is B. H. Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III King of Assyria (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), although here we will use ANET as a more convenient edition.

[5] As a record of the yearly governors against which the major campaign for that year is noted, the Eponym List is a valuable baseline for correlating the annals and inscriptions; for a convenient text see Thiele, Mysterious Numbers, 221-225. Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, 232-237, offers a table with his correlation of Tiglath-Pileser’s Calah Annals and various inscriptions to the Eponym dates.

[6] See J. H. Hayes and P. K. Hooker, A New Chronology for the Kings of Israel and Judah (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1988); M. C. Tetley, The Reconstructed Chronology of the Divided Kingdom (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2005).

[7] This division is chosen because Jehu deposed the reigning kings of Judah and Israel in this year and there is a fairly secure external synchronism with the annals of Shalmaneser III which dates tribute from Jehu to the year 841. See B. Halpern, “Yaua, Son of Omri, Yet Again” BASOR 265 (1987): 81-85 for a recent decisive discussion against P. K. McCarter, “Yaw, Son of ‘Omri’: A Philological Note on Israelite Chronology” BASOR 216 (1974): 5-7. Thiele argues for 841 against McCarter in “An Additional Chronological Note on ‘Yaw, Son of Omri’” BASOR 222 (1976): 19-23.

[8] An illustration of this is the records about Ahaziah, king of Judah (2 Kgs 8:25-26; 9:29), which have him begin his reign in the 11th and 12th year of the reign of Joram king of Israel and spell his name differently.

[9] For a discussion of this difference in dating and the evidence see D. J. A. Clines, “Regnal Year Reckoning in the Last Years of the Kingdom of Judah” in his On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays, 1967-1998 (2 vols; JSOTSup 292; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 1:395-421.

[10] For example, Asa dies in his 41st year (2 Chron 16:13), but his reign is given as 41 years (1 Kgs 15:9-10).

[11] For a discussion of the evidence see D. J. A. Clines, “The Evidence for an Autumnal New Year in Pre-Exilic Israel Reconsidered” in his On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays, 1967-1998 (2 vols; JSOTSup 292; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), 1:371-394.

[12] An accompanying spreadsheet has been placed on the EJournal website under “Downloads”.

[13] For a discussion of the syntax see R. J. Williams, Hebrew Syntax: An Outline (2nd Ed.; Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976), sections 200, 500.

[14] This is just the observation that the Kings includes source materials with complimentary historical perspectives.

[15] Mysterious Numbers, 63, 129-131.