In the first article (Feb. 1998, p. 53) we showed that we cannot equate the Valley of Jehoshaphat of Joel’s latter-day prophecy either with the River Yarmuk in Gilead, associated with Jehoshaphat’s alliance with Ahab against Syria, or with the Valley of Berachah, associated with the great victory which God gave Jehoshaphat over an invading army from Ammon, Moab and Edom. The second article showed that, though Megiddo is often associated with the latter-day invasion of Israel by the armies of the nations, Jehoshaphat has no known association with the Valley of Megiddo. It also showed that the Valley of Kidron, outside the walls of Jerusalem, and often considered to be the Valley of Jehoshaphat, is not particularly associated with Jehoshaphat, and is far too constrained to contain a large army.

Evidence from Joel

In Joel 3:12 the Valley of Jehoshaphat is the place where God judges the armies which have gathered against Israel. This should be linked with Joel 2:20: “but I will remove far off from you the northern army, and will drive him into a land barren and desolate, with his face toward the east sea, and his hinder part toward the utmost sea, and his stink shall come up, and his ill savour shall come up, because he hath done great things”.

The “utmost sea” was the western boundary of the tribe of Judah according to Deuteronomy 34:2, and cannot be other than the Mediterranean. The “east sea” has usually been assumed to be the Dead Sea, but it does not seem to be referred to as this anywhere else in Scripture, although it is certainly east of much of Israel’s territory. The “east sea” of Joel appears to correlate with the “eastern sea”, the marginal alternative for the “former sea” in Zechariah 14:8. This is the body of water into which the new Jerusalem river will eventually empty after reviving the waters of the Dead Sea, and thus denotes the present Persian Gulf.

This suggests that the best candidate for the Valley of Jehoshaphat is the Great Rift Valley, running from the Gulf of Aqaba in the south to the emergence of the River Jordan from the foothills of Mount Hermon in the north. However, to which part does it relate?

The territory adjacent to the north part of this valley cannot be described as “a land barren and desolate”. According to Daniel 11:41, Ammon, Moab and Edom are to escape occupation by the northern invader, and Moab appears to grant sanctuary to Israeli refugees from the invasion (Isa. 16:4), so the invading army cannot be driven into the area east of the Dead Sea. A further reason for excluding the northern part of the Great Rift Valley from being the Valley of Jehoshaphat is that, if the invading armies are destroyed there, they would not actually reach the rest of the land; yet Ezekiel 38:9,16 says that they will come “like a cloud to cover the land”. For these reasons we narrow our consideration of the Great Rift Valley as the Valley of Jehoihaphat to that part south of the Dead Sea, known as the Arabah.

Jehoshaphat’s invasion of Moab

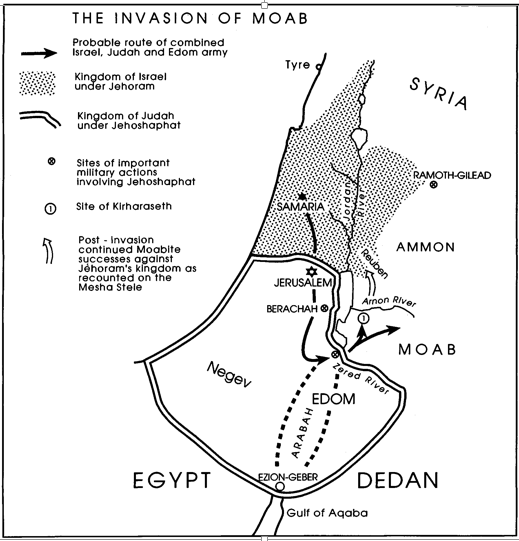

We turn our attention now to another episode in the life of Jehoshaphat, the invasion of Moab by a joint force from Israel, Judah and Edom, as recorded in 2 Kings 3. We have an association of Jehoshaphat with Edom recorded in 2 Chronicles 20:35-37, which records the abortive joint venture of Jehoshaphat and Ahaziah of Israel to send ships from Ezion-geber to Tarshish. Eziongeber is at the southern end of the Arabah, at the top of the Gulf of Aqaba and reckoned to be the southern limit of Edom.

Following Ahaziah’s death, his brother Jehoram succeeded him on the throne of Israel and requested Jehoshaphat’s assistance in recovering Moab to his dominions (2 Kgs. 3:7), with Edom joining the alliance (v. 9). The invasion route was through apparently familiar territory: the Arabah (v. 8). The distance from Jerusalem to the Arabah is slightly over fifty miles, but the steep and difficult wilderness terrain would have increased it considerably. Large forces often cannot move quickly anyway, and the narrow trails would have necessitated slow movement, especially when the army was accompanied by livestock (v. 9). Seven days for this march is not an inordinate length of time, but the slow pace through parched countryside led to a dangerous depletion of the water supply and a defeatist attitude in the king of Israel (v. 10).

Jehoram’s blaming of God for the predicament led Jehoshaphat to ask for God’s advice through Elisha. Out of regard for Jehoshaphat, God commanded that ditches be dug throughout the valley. If the valley floor was hard-baked desert, this would have been hard, thirsty work, but it was accomplished at Jehoshaphat’s direction and demonstrated anew his faith, as the enemy was not far away. At the time of the following morning’s sacrifice the country was filled with water from Edom, to the south, without any accompanying wind or rain. This is recognisable as a ‘flash flood’, which can originate in rainstorms miles away.

Any possibility of surprise had been lost due to the slowness of the advance, and the Moabites had assembled at the southern border of their country, marked by the River Zered which enters the Dead Sea at the east side of the Arabah (v. 21). By the time the Moabites actually came in sight of the tents of the allies the water had arrived. The rising, like the setting, sun can be extremely red, and the water looked like blood. The Moabites appear to have thought that a repetition of the Berachah slaughter had occurred, with themselves as the beneficiaries this time (vv. 22,23; cf. 2 Chron. 20:23).

Unlike the apparently organised gathering of valuables in the Valley of Berachah (2 Chron. 20:25-30), the Moabites appear to have been intent on individual personal enrichment. The allied forces had retained their order, and drove the Moabites back in a disastrous retreat, which subsequently led to the devastation of their country, in accordance with God’s commands.

The terseness of the account of the remaining events (2 Kgs. 3:25-27) indicates that, notwithstanding the success of the invasion, Israel’s control of Moab was not re-established. However, this does not detract from the magnitude of Jehoshaphat’s triumph in the battle in the Arabah. Unlike at Berachah, the rout of Moab was due to actually engaging the enemy in combat. It was used by God to enhance Jehoshaphat’s reputation, both as a faithful servant of the Lord and as a brilliant military commander. Given this, it would be no surprise if the Arabah was also called the Valley of Jehoshaphat.

More on the Arabah

There are additional points in favour of equating the Arabah with the Valley of Jehoshaphat. In terms of past precedent for possible future repetition, the Arabah has already witnessed a spectacular instance of Divine judgement on Gentiles, when Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed by a rain of fire and brimstone (Gen. 19:24). If the Arabah is the “valley of decision” (Joel 3:14) it may be that fire and brimstone will again be poured out upon the wicked here (Ezek. 38:22). This bombardment may be a key factor in precipitating the enemy’s panic (v. 21).

The designation ‘Arabah’ is sometimes used for the entire Rift Valley, from the Sea of Galilee south to the Gulf of Aqaba. However, the region north of the Dead Sea is also referred to as the ‘Ghor’, and we have termed it the Jordan River Valley. The Arabah we restrict, in accordance with general modern usage, to that part of the Rift south of the Dead Sea. Both the northern half of the Arabah, which ascends southwards to above sea level, and its southern descent again to Ezion-geber, are about sixty miles long and up to ten miles wide. Each part is thus sufficiently large to contain hundreds of thousands of modern troops, including their weaponry and transport.

The lands to both the west and the east of the Arabah are among the most barren and desolate on the planet. To the east of the Arabah are the mountains of Edom, or Seir. Whatever vegeta-

tion, forest or pastureland supported the ancient Edomite people has long since been almost completely denuded, and the area nowadays has a very sparse, mostly nomadic, population.

Isaiah prophesies of a great future slaughter in Idumea, or Edom, and a sacrifice in Bozrah (Isa. 34:6). He also refers rhetorically to one who comes from Bozrah after a bloody military action in the day of vengeance (63:1-6), and this seems to be elaborated on by Habakkuk in his prophetic prayer of an advance from Teman, in west-central Edom, and Mount Paran (Hab. 3:15). These seem to support the driving of the disorganised survivors of slaughter and catastrophe in the Arabah ‘Valley of Jehoshaphaf eastwards into the barren and desolate land of Edom, where they are then destroyed by the forces of the returned Christ.

Why gathered in the Arabah?

The question remains as to why the forces of the invader should be gathered in the Arabah. The reason for building up enormous armies in desolate or sparsely inhabited areas is because they are strategically important. Modern Jordan is devoid of oilfields, valuable mineral deposits or fertile soils, and therefore has a relatively low population. Its strategic importance has been minimal since ancient times because it is remote from major commercial arteries between population centres in Egypt and the north.

This is noted in its escape from the onslaught which engulfs the land west of the River Jordan (Dan. 11:41). Jordan remains neutral when both Israel and Egypt, along with other unspecified countries, succumb to the northern invaders (vv. 42,43), and is too weak itself to pose a threat to them. The forces gathered in the Arabah must thus be there either for anticipated further offensives or to counter a tangibly powerful opposition in Saudi Arabia, beyond Jordan’s southeastern border.

Daniel’s account of this “time of the end” mentions a “push” from the “king of the south” which precipitates the invasion of the “king of the north” (v. 40) into Israel and Egypt. Egypt is mentioned by name, whereas the king of the south is left undefined, so they may very well not be the same power. In Ezekiel’s version of the great northern invasion, an outcry is raised by various powers, among which is ancient Dedan, located south and east of modern Jordan (38:13). If the military forces of Daniel’s king of the south, corresponding to Ezekiel’s protesters, were massed on Jordan’s southern and eastern frontiers, it would prompt a marshalling of the invaders’ armies in the Arabah.