The Holy land has an extremely varied topography, ranging from flat Mediterranean coastal plains, through rolling prairie and hill country, to mountainous interior uplands. There is a range from heights of more than 9,200 feet (3,000 metres) in the northern Mount Hermon region to depths of more than 1,300 feet (400 metres) below sea level in an enormous north-south inland trench. Thus the area has many small and large valleys. Due to considerable difference in annual rainfall, the vegetation covering hills and valleys can vary from tropical lushness to barren desert.

Many of the valleys are referred to in Biblical histories, and, despite the use of alternative names for the same locality, can be readily identified today from the context of events or physical descriptions. Because of climatic variations or foreign exile of the inhabitants due to invasions, the exact positions of some geographic features have become either lost or debatable. On occasion, in Scriptural prophecy, sites are mentioned for which there appears to be neither documentary nor archaeological evidence for their whereabouts. Consequently these locations are sometimes held to be metaphorical and never to have existed in the past. Not having been real places, the search for a geographic site where the prophesied events are to occur is considered an exercise in futility.

This is the case with the Valley of Jehoshaphat, where a great defeat is to be inflicted on an international northern alliance which will invade the land of Israel (Joel 3:2,12). No definite location has been established for this site, leading some to characterise it as merely symbolic because the name Jehoshaphat means ‘Yahweh has judged’.

The invasion forecast by Joel’s prophecy is echoed by other prophets, who depict a great influx of northerners which is subsequently overcome by direct Divine intervention, and frequently involves the appearance of Israel’s Messiah. It has been maintained that different prophets have referred in their writings to several separate invasions which are to take place in the last days before the Messiah’s coming. As almost all of these northern invasion accounts either openly state, or otherwise imply, that the land will be occupied by Abraham’s progeny when it occurs, it is the position in this investigation that there will be only one great invasion from the north at the time of the end, and that different prophets were given various details concerning it.

The indication that the beginning of the overthrow of this invasion is the first manifestation to the world at large of the power of its Divinely ordained future ruler means that its location assumes some importance. The repulsion of the northern invaders starts in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, which thus must be a tangible geographic feature.

This exploration examines aspects of Jehoshaphat’s activities, the general topography of the Holy Land, and previously put forth possibilities for its location, along with the coordination of other invasion prophecies, to arrive at a positive identification of the Valley of Jehoshaphat within the confines of the Holy Land.

Jehoshaphat’s career

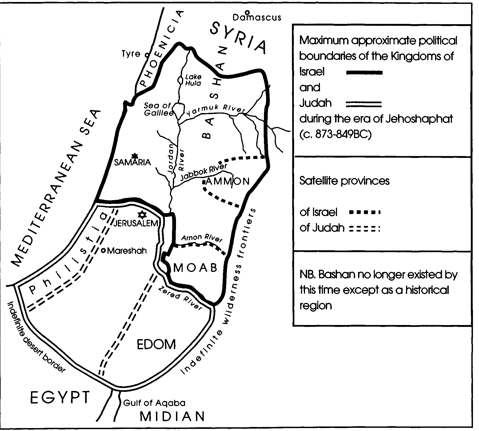

Jehoshaphat (c. 873-49 B.C.), through preparing his heart to seek after God (2 Chron. 19:3), eventually became one of the most powerful kings of Judah (20:29,30). However, with Egypt quiescent since his father Asa’s overwhelming rout of Zerah the Ethiopian at Mareshah (14:9-15; c. 897 B.C.), Jehoshaphat tried to mend the split between Judah and Israel, which had seceded some

fifty years before (1 Kgs. 12) and had warred constantly with Asa (15:32).

In this sphere Jehoshaphat’s policies were superficially successful. However, the involvement of Judah’s house of David with Israel’s wicked and idolatrous house of Omri spread the infection of compromise with paganism into Judah (2 Chron. 21:6), and was repeatedly condemned for the evil it would bring upon the country when those of less upstanding character than Jehoshaphat succeeded to the throne.

In pursuing reconciliation, Jehoshaphat supported Israel’s attempts to retake tribal territories lost to foreign invasion, and to suppress revolt in its outlying non-Israelite provinces. He thus became enmeshed in the politics and wars of the surrounding regions of Philistia, Israel, Syria, Ammon, Moab and Edom. This means that there is a large area in which a valley could legitimately have been named after him. The events of Joel’s prophecy are military, however; and, assuming a symbolic type of precedent may have been set by Jehoshaphat, his conduct in this field becomes particularly relevant in this analysis. We will look at the events of Jehoshaphat’s reign to see if there is anything which could provide an origin for the name Valley of Jehoshaphat.

Yarmuk and Berachah

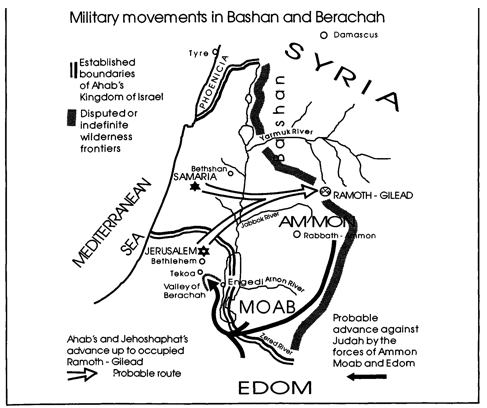

As a first step in establishing cordial relations with the northern kingdom, Jehoshaphat renounced Asa’s Divinely condemned anti-Israel alliance with Syria (2 Chron. 16) and, to rectify the evil which had come from the previous association, willingly joined King Ahab in an attempt to dislodge the Syrian occupation of Ramothgilead, in the upper reaches of the Yarmuk River watershed east of the River Jordan. During the battle Jehoshaphat impersonated Ahab and was almost killed before managing to escape from the Syrians. Ahab himself, despite being mortally wounded, evidently remained prominently on the battlefield until the fighting ceased and he died (1 Kgs. 22:1-4,29-37).

The Battle of Ramoth-gilead appears to have been a stalemate, for, while Israel dispersed after Ahab’s death (v. 36), Jehoshaphat made an orderly withdrawal and returned in peace to Jerusalem (2 Chron. 19:1). He appears never again to have been involved in war with Syria. It is unlikely that there is anything here which would warrant the Yarmuk Valley being renamed the Valley of Jehoshaphat.

Although Jehoshaphat was extricated from personal peril by God (18:31), the Lord’s wrath was upon him for consorting with the idolatrous king of Israel (19:2). This appears to have taken the form of severe damage to his military reputation, and consequent temporary loss of Judah’s hegemony over Edom. While Jehoshaphat was subsequently laudably concentrating on bringing the people of Judah back to God through internal reforms (19:4-11) he was beset by an invasion of Ammonites, Moabites and Edomites (20:1-24).

Moab had revolted after Ahab’s death (2 Kgs. 1:1), and its success apparently fomented popular uprisings in Ammon and Edom as the authority of Israel and of Judah wavered in the aftermath of the Syrian warfare. The rebels singled out Jehoshaphat’s realm for retaliation for the century of repeated servitude to the two states west of the River Jordan, probably because Judah was deemed the weaker realm under a poor commander.

Jehoshaphat’s forces were able to watch the self-destruction of their enemies while singing and praising God for their own deliverance. The differences between the former northern subjects, whose ancestries were traced to Lot (Gen. 19:37,38), and those of the southern kingdom, descended from Esau (36:19), were agitated by God into mutual slaughter, which then continued amongst the northerners themselves as a result of their own national peculiarities (2 Chron. 20:23).

There are distinct parallels between the outcome of this invasion and the overthrow of Gog, when “every man’s sword shall be against his brother” (Ezek. 38:21). The taking of abundant spoils from the fallen (2 Chron. 20:25-30) appears to portend the future looting by the survivors of Israel of those who have robbed, and intend to continue robbing, them (Ezek. 38:11, 12; 39:10).

However, Jehoshaphat’s contribution to this victory was limited to exhorting his people to belief in and obedience to God, setting a personal example in his own conduct, appointing those who were to lead in singing God’s praises, and organising the array of his forces before the battle. He evidently also oversaw the systematic removal of the plunder (2 Chron. 20:20,21,2528). The glory for this triumph was given completely to God; and the valley in which it was effected, southeast of Jerusalem between Tekoa and the Dead Sea town of Engedi, was not named after Jehoshaphat, but was called Berachah, or ‘blessing’, because there the people of Judah blessed the Lord (vv. 16, mg., and 26).