In Joel 3:12-14 “the valley of Jehoshaphat” seems to be the same as “the valley of decision”, in which multitudes of invaders will be gathered. The phrase “Multitudes, multitudes” reinforces the idea that he is referring to the strength of entire armies being massed in a valley bearing Jehoshaphat’s name.

This is an important point because it means that the valley into which the “mighty men” of the Gentile nations will be gathered (vv. 9-11) must be sufficiently large to accommodate both the military personnel and the considerable equipment which accompanies modern mechanised warfare. Thus most, if not all, of the smaller valleys located among the hills and mountains of the central portion of the Holy Land must be automatically excluded from being “the valley of Jehoshaphat”.

Megiddo

The word “decision” in the phrase “the valley of decision” is rendered in the margin as ‘concision’ (meaning ‘cutting off’) and ‘threshing’ (v. 14). The latter translation seems to link with the proposal, ‘a heap of sheaves in the valley of threshing’, for the meaning of the name Armageddon (Rev. 16:16). The site of Armageddon has been equated with “the valley of Megiddon” (Zech. 12:11) in northern Israel beneath the ancient fortress of Megiddo at the eastern end of the Mount Carmel ridge system. This largest east-west depression in the Holy Land is also referred to as “the plain of Megiddo”, “the plain of Esdraelon” and “the valley of Jezreel” after another ancient city at its eastern end.

The Valley of Megiddo was well beyond the northern borders of Jehoshaphat’s kingdom of Judah, and there is no direct Scriptural reference to his going there. Jehoshaphat’s absence from this region makes it unlikely that this large valley would even temporarily have been known as the Valley of Jehoshaphat.

Kidron

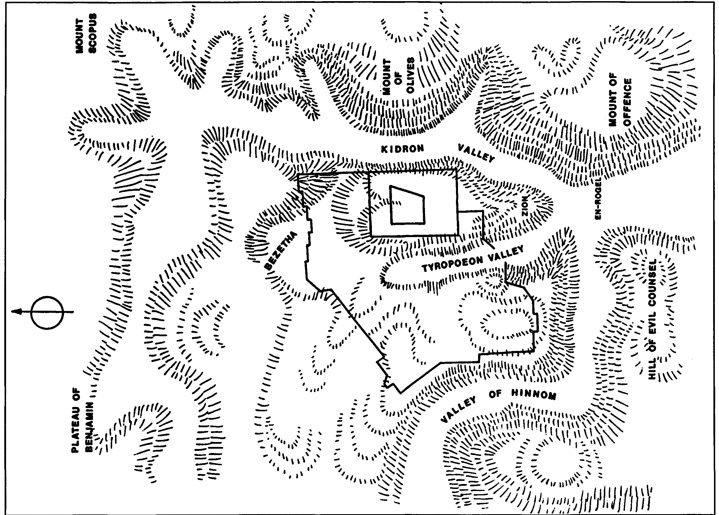

In the fourth century A.D. the suggestion was advanced that the Valley of Jehoshaphat was the Kidron, or Cedron, Valley which separates the city and Temple Mount of Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives to their east. This solution is still espoused by most in Christendom because it seems to fulfil a number of geographical and prophetical requirements, and is apparently reinforced by symbolic historical precedents.

The Kidron Valley is a prominent topographic feature, and might easily have borne Jehoshaphat’s name during and shortly after his reign. Joel is believed to have prophesied about thirty years following Jehoshaphat’s death. The Kidron was where pagan idols, altars, and the bones of idol-worshippers and heathenised priests were burned and ground to powder during reforms. This could presage the demise of the latter-day Gentile multitudes under a hail of fire as well as by the sword (Isa. 66:16).

However, the main destructions in the Kidron were carried out by Asa (1 Kgs. 15:13), and Jehoshaphat is stated not to have eradicated the idolatrous “high places” (22:43). That leaving some of these “high places” formed part of Jehoshaphat’s reconciliation policy with Israel cannot be ruled out. Further operations against pagan practices were later launched by Hezekiah (about 700 B.C.; 2 Chron. 30:14) and Josiah (about 630 B.C.; 2 Kgs. 23:4,6,12) in the Kidron Valley.

Even in Joel’s day, however, it would have been more appropriate for the Kidron Valley to have been named after Asa rather than Jehoshaphat.

Identification of the Kidron Valley with that of Jehoshaphat was also based on equating the prophesied events in Joel 3 with the view that Christ will return to dispense judgement upon the wicked at the same place where he ascended to heaven—the Mount of Olives (Acts 1:9-12). Ancient Judaism’s concept that the Messiah would appear in this vicinity led, in anticipation of his arrival here, to a proliferation of graves throughout the valley and on the slopes of the Mount of Olives. For accepters of the New Testament, this interpretation ignores the fact that the two men in white told the apostles who had witnessed his ascension that Christ would return in the same “manner”; no mention of where was stated, only how (v. 11). Certain Old Testament references (Hab. 3:3; Isa. 63:1) indicate that at the time of the end the Messiah would first appear in Edom to the south before arriving at Jerusalem.

The relatively small size of the Kidron Valley, even if its northern limits are extended so that it includes the area between the Old City of Jerusalem and Mount Scopus, mitigates against it being the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Though periodically occupied by besiegers of Jerusalem since David’s taking of the city, the Kidron Valley does not seem to have been the mustering area for any overwhelming assaults on its walls, which have usually been breached on the north or west. Although the annihilation of the Assyrian army of 185,000 might be cited as a precedent for the future destruction of the Gentile forces, this did not occur in the Kidron Valley. Hezekiah was assured that the Assyrians would not lay siege to the city (Isa. 37:33), but if the Assyrians were encamped in the Kidron it would constitute a de facto cutoff of access.