Introduction

The identity of Immanuel is disputed and different suggestions have been proposed. This article will argue the case that Immanuel is Hezekiah. The problem with identifying Hezekiah as Immanuel are two-fold; (1) It is disallowed by the chronology of Hezekiah’s life; and (2) Even with an ‘adjusted’ chronology it is ruled out by the date of the Syro-Ephraimite war.

The Chronology of Hezekiah

Proponents of Hezekiah as Immanuel have offered the solution that Hezekiah was 15 instead of 25 when he began to reign and conjectured a textual corruption in the MT where either the numerals[1] or the numeral-words[2] were misread. The online Encyclopaedia Judaica entry states,

Nor is it definitely known how old Hezekiah was when called to the throne. II Kings xviii. 2 makes him twenty-five years of age. It is most probable that “twenty-five” is an error for “fifteen.” (p. 20)

G. Galil affirms,

Alternatively, it has been proposed that Hezekiah was 15 and not 25 at his investiture, or that Ahaz was 25 years old and not 20 when he began to rule (as is asserted by the Septuagint for II Chronicles 25:1).[3]

Textual degradation is caused by transmission errors and does not reflect on the inspiration of the original text. The sections we are dealing with are concerned with historical reportage and probably rely on royal annals as source documents.[4]

In Aramaic inscriptions, numerals occur as early as the eighth century BC. A bronze lion weight found at Nineveh (8th century) has the number 15 expressed in three different ways using both numbers and numeral words. In the time of Isaiah (c. 700 BC), the Hebrews used the old Phoenician script, in which the waw and yod were not plain strokes, and most probably did not use the alphabetic but the Phoenician or Aramaic numerals, that did have the form of simple strokes.[5]

H. L. Allrick traces the Aramaic numbering system back to the eighth century. In Aramaic, vertical strokes are used for units and horizontal strokes for tens. The vertical digit strokes were generally grouped in threes. For the hundreds, a stylized mem was used, plus vertical strokes to indicate how many hundred; for the thousands an abbreviation of the word was used, together with strokes to indicate how many thousand. “As for the Hebrews themselves”, he says, “there is no doubt they too employed the same principles of numerical notation.”[6]

J. W. Wenham adds,

“It is easy to see how such a system, whether through defects of writing or of the material used or through scribal carelessness, would lead to the misreading of a number—usually making it one too big or one too small”.[7]

Nevertheless, it is always preferable to assume that there is no transmission error involved and that problems exist because the data is misunderstood and therefore incorrectly synchronised. The era from Uzziah to Hezekiah is notoriously difficult to date as overlapping co-regencies existed and synchronizing Judean kings with northern Israelite monarchs is further hampered by rival regencies and retroactive regnal counts. Scholars have recognised this problem as the following Wikipedia survey[8] states,

Since Albright and Friedman, several scholars have explained these dating problems on the basis of a co-regency between Hezekiah and his father Ahaz between 729 and 716/715 BC. Assyriologists and Egyptologists recognize that co-regency was a practice both in Assyria and Egypt.[9] After noting that co-regencies were only used sporadically in the northern kingdom (Israel), Nadav Na’aman writes, “In the kingdom of Judah, on the other hand, the nomination of a co-regent was the common procedure, beginning from David who, before his death, elevated his son Solomon to the throne…When taking into account the permanent nature of the co-regency in Judah from the time of Joash, one may dare to conclude that dating the co-regencies accurately is indeed the key for solving the problems of biblical chronology in the eighth century B.C.”[10] Among the numerous scholars who have recognized the co-regency between Ahaz and Hezekiah are, Kenneth Kitchen in his various writings,[11] Leslie McFall,[12] and Jack Finegan.[13] McFall, in his 1991 article, argues that if 729 BC (that is, the Judean regnal year beginning in Tishri of 729) is taken as the start of the Ahaz/Hezekiah coregency, and 716/715 BC as the date of the death of Ahaz, then all the extensive chronological data for Hezekiah and his contemporaries in the late eighth century BC are in harmony. Further, McFall found that no textual emendations are required among the numerous dates, reign lengths, and synchronisms given in the Hebrew Testament for this period”.[14]

Essentially, A. Perry adopts the same synchronism in his spreadsheet ‘Kings Chronology’[15] and this dates the birth of Hezekiah to 740. Surprisingly, other scholars achieve approximately the same birth year by emending the age of Hezekiah. This article will therefore employ ‘Kings Chronology’ by Perry for the biblical chronology as it provides a more elegant solution than textual emendation. This removes the chronological difficulty surrounding Hezekiah’s birth. However, as Perry points out, the Immanuel prophecy is dated to the Syro-Ephraimite Crisis of 735/734[16] and this is determined by Assyrian chronological records. This would mean that Hezekiah was born 5-6 years before the prophecy was given rather than less than a year after the prophecy. This is a seemingly insurmountable problem but only if the eponym chronicles and biblical records have been correctly aligned. When we examine the primary records it becomes apparent that certain assumptions are made, particularly with regards to the Biblical records, where certain accounts are deemed to be parallel reports when they are clearly not.

The Primary Biblical Records

The primary biblical records are 2 Kings 15 and 16, 2 Chronicles 28, Isaiah 7 and Hosea 5 and 6. Many scholars posit contradictions in the OT account of the Syro-Ephraimite war and attempt either to harmonise or dismiss the differences. Is the account contradictory or just poorly understood?

The most glaring contradiction is the appeal by Ahaz for Assyrian assistance against Rezin and Pekah. In both Kings and Chronicles, either tribute or inducements (garnered from the temple) are sent to Tiglath-Pileser III (henceforth Pul), with an urgent request for help. In 2 Chron 28:20, no help is offered; in fact the opposite is the case, as Pul “distresses” Ahaz (LXX lit., “struck him a blow”). As a consequence, Ahaz turns to the “gods of Damascus” (Baal) because they were effective in helping his enemy Rezin. In contrast, the account in 2 Kgs 16:7-13 has Pul respond positively to an appeal for assistance against Rezin and Pekah. Assyria defeats the confederation; as a consequence, Ahaz turns to the Assyrian god (Ashur) and has a copy made of the Assyrian altar.[17]

Whereas one account has Rezin capturing Elath (2 Kings 16), the other account describes an Edomite and Philistine invasion (2 Chronicles 28). Rather than harmonizing the account or dismissing the differences as ideologically motivated (to suit the theological motif of the author) it is entirely possible that we are dealing with two different invasions by Syria and Ephraim. The invasion in 2 Chronicles 28 (which is parallel with Isaiah 7) is different to the invasion described in 2 Kings 16.

2 Chronicles 28 parallel with Isaiah 7

The 2 Chronicles’ account states the following;

Wherefore the Lord his God delivered him into the hand of the king of Syria; and they smote him, and carried away a great multitude of them captives, and brought them to Damascus. And he was also delivered into the hand of the king of Israel, who smote him with a great slaughter. 2 Chron 28:5

Chronicles differentiates the attacks by Israel and Syria – Ahaz was delivered to Syria and also to Israel – it seems that at this stage Syria and Ephraim operated independently; they were as yet not confederated. Neither Syria nor Ephraim could capture Jerusalem (Isa 7:1)[18] but they wreaked havoc in the countryside of Judea; captives and spoil were transported to Damascus; Ephraim also took captives and plunder. However, at the conclusion of these invasions Syria and Ephraim determined to coordinate their next efforts and plotted that any future invasion would result in replacing Ahaz with a lackey of the confederation, the “son of Tabeal” (Isa 7:6).

This new intelligence (provided by Isaiah) came as shock to the house of David especially as they had to deal with the loss of much of the royal cabinet and the king’s son Maaseiah[19] during the conflict (2 Chron 28:7) and now they were facing the possibility of the end of the Davidic dynasty. H. Cazelles offers an intriguing suggestion in his support of equating Ben Tabeal with a son of Tubail.[20] He thinks that Tabe’al is an Aramaic form of Phoenician ‘Ittoba’l. Furthermore, he proposes that the announcement of a ‘dynastic heir’, named Immanuel (= ‘God with us’) in 7:14 is Isaiah’s use of a ‘parallel name’ in response to the attempt by Rezin and Pekah to place ‘Ittoba’l (‘Ba’al with him’) on the throne in Jerusalem.

It is at this point that Isaiah enters the scene accompanied[21] by his son Shear-jashub (a remnant returns) in anticipation of the captives that would be sent home at the urging of the prophet Oded (2 Chron 28:8-15). It is notable that the prophet Oded appealed to the “chiefs of Ephraim” and not to Pekah and this may indicate that there were still internal tensions regarding the manner of his rise to power or his legitimacy. After giving the Immanuel prophecy, Isaiah issues the following warning:

The Lord shall bring upon thee, and upon thy people, and upon thy father’s house, days that have not come, from the day that Ephraim departed from Judah; even the king of Assyria. And it shall come to pass in that day, that the Lord shall hiss for the fly that is in the uttermost part of the rivers of Egypt, and for the bee that is in the land of Assyria. Isa. 7:17-18

The “uttermost part of the rivers of Egypt” is the brook of Egypt, which formed the border between Philistia and Egypt (2 Chron 9:26). P. S. Evans observes that,

One of the most famous gods of Philistia is Baal-zebub “Master of the flies,” known as the god of Ekron (2 Kgs 1:2, 3, 6, 16). In fact, in the entire HB/OT the word bwbz occurs in reference to the god of Ekron, Isa 7:18 and Qoh 10:1.[22]

Ahaz is being warned about the Philistines and the Assyrians. Isaiah 7:17-18 is prophesying about the still future invasion that is reported in 2 Chron 28:16-20. The warning about Assyria is further elaborated in Isaiah 8 with the naming of Maher-shalal-hash-baz (Isa 8:1) which means “quick to spoil speedy to prey”. The second half of Chronicles 28 describes an attack by Philistia (and Edom) and Assyrian refusal to help Ahaz (v. 16); instead, Pul “distresses” him (v. 20). The translations offer the alternatives, “oppress/troubled/afflict” and report that he (Tiglath-Pileser) “came unto him”.

2 Kings 15

The account in 2 Chronicles 28 narrates events from the perspective of Judah. It commences with the invasion(s) of Pekah and Rezin and concludes with Philistia, Edom and Assyria troubling Judah. In contrast, the account in 2 Kings 15 provides a summary of events for the whole period from a northern Israelite perspective. The history it presents is compressed; it mentions the tribute payment made by Menahem (vv. 19-20) and the northern Assyrian campaign in 733 (v. 29) and concludes with the assassination and replacement of Pekah with Hosea (v. 30) and with the general statement, “In those days (the days of Jotham) the Lord began to send against Judah Rezin the king of Syria, and Pekah the son of Remaliah” (v. 37).

2 Kings 16

The account in 2 Kings 16 compliments the previous chapter and provides more details about the events that resulted in the demise of northern Israel. This account describes the confederated invasion of Pekah and Rezin in 736-735 (known as the Syro-Ephraimite war) and the attempt to replace Ahaz with a puppet king (as predicted by Isaiah) thereby creating an anti-Assyrian block. The attack was deliberately timed to coincide with Tiglath-Pileser’s absence in the region, as during this period he was campaigning in the east fighting among the Urartians and Medians. Once again Jerusalem was besieged (v. 5) and Rezin captured Elath (v. 6),[23] but this time Pul responded positively to the appeal by Ahaz, this resulted in the northern campaigns in Israel and Aram-Damascus of 732 and 733 which resulted in downfall of Pekah and Rezin and which are summarily referred to in 2 Kings 15. The two sections of 2 Kings 16 use differing ways of referring to Ahaz (“Ahaz in 16:5-9; “King Ahaz” or “the king” in 16:10-18) and different spellings of the name “Tiglath-Pileser” (rslp tlgt in 16:7; rsalp tlgt in 16:10). It seems that two different sources were used and that they were “joined” by a section (vv. 10-18) that describes Ahaz’s apostasy.

Hosea 5:8-6:6

In 1919, A. Alt argued that this text reports on a Judean counter-attack against Israel immediately following the end of the siege of Jerusalem.[24] However, P. Arnold has recently offered a detailed refutation of Alt’s theory while maintaining the connection of this text with the general background of the Syro-Ephraimite war.[25] He examines the geographical detail and suggests that the oracle describes an initial Israelite march against Jerusalem.

The Primary Assyrian Chronicles

The Assyrian Chronicles summarised below (with corrected footnotes) are derived from B. E. Kelle, Hosea 2: Metaphor and Rhetoric in Historical Perspective (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2005), 185f:

- Layard 45b+III R 9, 1 (Tadmor Ann. 2 1): This text is the earliest relevant text of Tiglath-Pileser III and dates to around 743-740 B.C.E.[26] The inscription details the tribute paid by Rezin of Damascus and other neighbouring states but does not mention Samaria. Nonetheless, some scholars maintain that the inscription has lost the phrase “Menahem of the land of Samaria” and it should he restored in the available space.[27]

- Iran Stela: This text is a fragmentary summary inscription found in western Iran.[28] Column II, lines 1-23 preserve a list of Anatolian and Syro-Palestinian rulers on whom Tiglath-Pileser III imposed tribute. This list includes “Menahem of the land of Samaria.” The inscription seems to date to the time of Tiglath-Pileser’s Ulluba campaign in 739-738 because it presupposes a period when the Assyrian army was in Iran and names Tubail as the king of Tyre rather than Hiram, who was involved in the 734-732 campaign.[29]

- Layard 50a+50b+67a: This inscription is a fragmentary annals text that consists of twenty-four lines recording Tiglath-Pileser’s military achievements in his eighth and ninth pale (738-737 and 737-736). The discussion of these achievements includes the receipt of tribute from western states in Syria-Palestine and mentions “Menahem of the city of Samaria.” The text is nearly identical to the Iran Stela and scholars are virtually unanimous in dating the tribute list to 738-737 because of the text’s later reference to the ninth palû.[30]

- II R 67: This text is a fragment of a long summary inscription of Tiglath-Pileser that summarizes the achievements in his first seventeen pale. Line 11 of the reverse contains a tribute list that mentions “Jehoahaz of the land of Judah”. The tribute list should be dated prior to 733 because it refers to “Mitini of the land of Ashkelon” who was deposed by 733-732.[31] This text is the only reference to Judah in the Assyrian inscriptions prior to 720 B.C.E.

- Layard 29b: There is much debate about whether to reconstruct this text to include a reference to the northern kingdom. The inscription describes Tiglath-Pileser’s campaign against Syro-Ephraimitic states after he left Philistia in 733. The relevant portion of the text is broken but refers to Assyria’s capture of a certain district’s territories in the Galilee region (11. 230ff). The text may be reconstructed to indicate that these territories belonged either to “Bit-[Hazael]” or “Bit-[Humri].”[32] The reconstruction has implications concerning the size and status of the northern kingdom in the waning years of the conflict.

- Layard 66: This text describes events at the end of the Syro-Ephraimitic war. The inscription is a fragmentary annals text that records Assyrian campaigns in the west from 732 to 731, including the subjugation of Queen Shamshi of Arabia.[33] The description in line 228 refers to Tiglath-Pileser’s treatment of “the city of Samaria”.

- III R 10, 2: This summary inscription from Nimrud also relates to the close of the Syro-Ephraimitic war. However, the text is not chronologically but geographically arranged and comes not from the time of the events themselves but from the period alter Tiglath-Pileser had settled affairs in Syria-Palestine.[34] At this stage in the course of’ events, the Assyrian scribes refer to the land of “Bit-Humri.”

- ND 4301+4305: This final relevant text consists of two fragments of a clay tablet and essentially parallels III R 10, 2.[35] Since this text mentions payment of tribute to Tiglath-Pileser at Sarrabanu in Babylon (1. 10), it seems to come from the time after Tiglath-Pileser had settled affairs in Syria- Palestine and left the region. As with III R 10, 2, this inscription refers to the border of the land of “Bit-Humri” (11. 3-4).

The build up to war

The build up to the war should be sought during the reign of Uzziah and his co-regent Jotham rather than in the days of Ahaz. Uzziah rebuilt Elath (2 Chron 26:2) and subjugated the Philistines, Arabians, Mehunims and the Ammonites (vv. 6-8), and built many fortifications. Jotham also built fortifications (2 Chron 27:4) and subjugated the Ammonites to tribute for three years (v. 5). Both Uzziah and Jotham followed the same policy and one suspects that although the successes are attributed to Uzziah, that it was actually his son and co-regent Jotham who implemented the strategies. It was obviously the intention of Uzziah/Jotham to control the major traffic routes — the sea route (coastal route via Philistia), the hill route (route through the Judahite hills), and the king’s route (Transjordanian route via Elath through Ammon). The suggestion is that Judean expansion, the capture of Elath and the three-year vassalage of Ammon occurred in the years 747-745 of the Uzziah/Jotham co-regency (year 746/747[36] was the first year of Jotham and the forty-first year of Uzziah). Year 746/7 was concurrent with the second year of Menahem and the fifth year of Pekah.[37] Northern Israel had two rival kings for a period with Menahem situated in Samaria and Pekah across the Jordan in Gilead.[38]

Galil observes that,

“The Gilead is a flexible territorial term, mentioned in the Bible more than 150 times. It often refers to small- and large-scale territories between the Arnon River in the south and the Yarmuk River in the north, and often even represents the Bashan. Determining the extent of the area ruled by Pekah is difficult, but this passage indicates that territories located in Transjordan were included within his kingdom……It is possible then, that Pekah was in charge of an administrative district, which included regions in the Bashan and in the Gilead, much like the son of Geber in the time of Solomon. In light of this proposal the passage in 1 Kgs 15,25 may be reconstructed thus: But Pekah the son of Remaliah, his officer in [the region of] Argob and [in the towns of] Jair, conspired against him. The fact that a company of fifty Gileadean warriors participated in the revolt supports this assumption. Apparently it was an élite unit at the disposal of Pekah, and was presumably used as his personal guard on account of his position as head of a district whose security was highly sensitive, especially around the Israel-Aram border. In light of the tight and unique bonds between Pekah and Rezin (which probably began prior to Pekah’s coronation: see 2 Kgs 15,37), it is not unreasonable to conclude that the Gilead was torn away from Israel and annexed to Damascus, in the time of Pekah. Moreover, if the above reconstruction is correct it is safe to assume that the Argob region was also included within the kingdom of Pekah (and not only the Gilead).”[39]

Judean control of the Transjordanian trade route and the port of Elath would be perceived as a threat to Pekah and Rezin as would the subjection of Ammon (Gilead’s neighbour) because control of the trade routes would severely impact revenues for both Pekah and Rezin. This would suggest a natural alliance between Rezin and Pekah to wrest control of the trade routes from Judah. Initially, resentment against Judah may have had little to do with forcing Judah to join an anti-Assyrian coalition but that changed after Pul ascended the Assyrian throne (745) and aggressively pushed the borders of the Assyrian empire outwards; over the next 14 years the Assyrian empire expanded from the region between the Euphrates and Tigris to reach almost to the Black Sea and the river Araxes in the north, and the Persian Gulf and northern Israel in the south. After Assyria subjected Pekah and Rezin to tribute payments, it would become even more urgent to capture the trade routes. Menahem raised his tribute in 740 by taxing his nobles, but that was obviously an unpopular move. As yet, Judah was not an Assyrian vassal and Assyria allowed Pekah and Rezin to operate an independent foreign policy until they grew too powerful. Galil concludes that,

“Practically, the Assyrians had no fixed policy towards conflicts between their vassals; they rather employed a flexible policy, dealing with each conflict on its own. The reaction was always motivated by the Assyrian interests, depending on circumstances…”[40]

Scholars such as J. Begrich[41] believe that the purpose of the Israel-Aram confederation was to force Judah to join an anti-Assyrian coalition: such a war would expose their northern flank to the Assyrians, weakening the coalition.[42] B. Oded, however, picked up the older view of Meissner and maintained that the Syro-Ephraimite war was strictly an inner-Palestinian conflict that had no relation to Assyria.[43] In his view, the conflict was the result of a battle among Syria, Israel, and Judah for control of territories in the Transjordan;[44] previous anti-Assyrian coalitions, such as that formed by Ahab and Ben-Hadad, had not waged war against states that refused to join them; and that Begrich was wrong to dismiss 2 Kgs 15:37, which shows that the Syro-Ephraimite war against Judah began in Jotham’s reign.[45]

Instead, Oded argues that an earlier longstanding Israel-Judah alliance against Syria that resulted in joint control over large parts of the Transjordan unravelled when Israel’s power declined during the series of revolutions and assassinations following the reign of Jeroboam II. This situation in turn enabled Uzziah of Judah to exert sole control over these areas, a situation which enabled Rezin of Syria to persuade Israel to ally with them and wrest control of the Transjordan back from Judah, with a second aim of installing Ben-Tabeel on the throne in Jerusalem. This war began during Jotham’s reign and ended when Assyria attacked the Syro-Ephraimite coalition. R. Tomes has recently revitalized Oded’s position and argued that no Assyrian text indicates the reason for the Syro-Ephraimitic attack on Jerusalem and the reason must he surmised from the biblical texts.[46]

Synchronizing the accounts

Oded remarked that it was wrong to dismiss 2 Kgs 15:37, which shows that the Syro-Ephraimite war against Judah began in Jotham’s reign. J. Edmund also observes that,

“Rezin and Pekah had been harassing Judah ever since the later years of Ahaz’s father, king Jotham. This would date the beginning of their harassment some time shortly before 742 BCE, before Jotham died, and before Ahaz became king. Therefore, according to the biblical texts, the Syro-Ephraimitic Crisis must have been an ongoing crisis for at least ten years or so”.[47]

A. K. Laina observes that,

“….the account of Isaiah supplements valuable information in understanding some of the details on the event. Notice the break between verse 1 and 2. After stating that “The king Rezin of Aram and Pekah son of Remaliah king of Israel marched up to fight against Jerusalem, but they could not overpower it,” verse 2 begins afresh “Now the house of David was told, ‘Aram has allied itself with Ephraim’, so the hearts of Ahaz and his people were shaken”. This construction highlights the severity of the new situation and explains why king Ahaz and his people were now in terror. First, the break affirms the circumstances of king Ahaz emphasised in 2 Chron 28:16. Second, the failure of their first individual invasion gives a logical reason for the formation of their alliance. Third, since king Ahaz and his people had already experienced the terror of their first attack, their united attack must have appeared to them invincible. Fourth, the alliances were so sure of their victory that they had designated their puppet king Tabeel to replace Ahaz (v.6) and thus it was a serious situation for Judah”.[48]

Moreover, we have recorded in 2 Kgs 15:19 that Pul “came against the land” of Israel during Menahem’s reign and in 2 Chron 28:20 Pul “came against” Ahaz to distress (strike a blow), yet no record of these incursions is found in the Assyrian Chronicles. Galil observes,

“The passage 2 Kgs 15, 19-20, which depicts the arrival of the Assyrian king in Israel and the offerings of Menahem, apparently refers to the subjection of Menahem in 740. It appears that Menahem’s reign was unpopular and a bond with Assyria was meant to strengthen the new dynasty in Israel. Indeed, the money owed to Assyria was not paid out of the kingdom’s treasury but collected from the Israelite nobles who probably resisted Menahem. The Assyrian sources do not relate any arrival of Tiglath-Pileser III in Israel in the time of Menahem. Yet it is possible that Tiglath-Pileser III’s inscriptions do not have details of the events of 742-740; consequently, the biblical testimony should not be rejected”.[49]

Elsewhere, when commenting on the problematic order of Tiglath-Pileser III’s campaigns in 734-732, Galil offers the following three reasons for the difficulties; (1) the majority of the Assyrian inscriptions are of a summary nature, and the few surviving annalist fragments provide only minor help in determining the order of the campaigns; (2) the Assyrian inscriptions are contradictory; (3) the Biblical testimony is insufficiently clear, and cannot be employed in deciding among the various reconstruction possibilities.[50] The difficulties that Galil recognizes for 734-732 is valid for the whole period from 745 onwards and 2 Kgs 15:19 together with 2 Chron 28:20 probably describe the same incident from Israelite and Judean perspectives. It is therefore methodologically preferable to reconstruct an independent biblical account and only once this is complete to attempt synchronization with Assyrian Chronicles.

We reconstruct the sequence of events in the boxes below. The dates are taken from Perry’s ‘Kings Chronology’ and dates with an asterisk (*) are the dates that scholars have determined from the Assyrian records (refer to the maps at the end of the article):

| 750 |

2 Kings 15. Pekah was contemporary with Jotham (vv. 26-27) and from 743 onwards with Jotham’s co-regent Ahaz. |

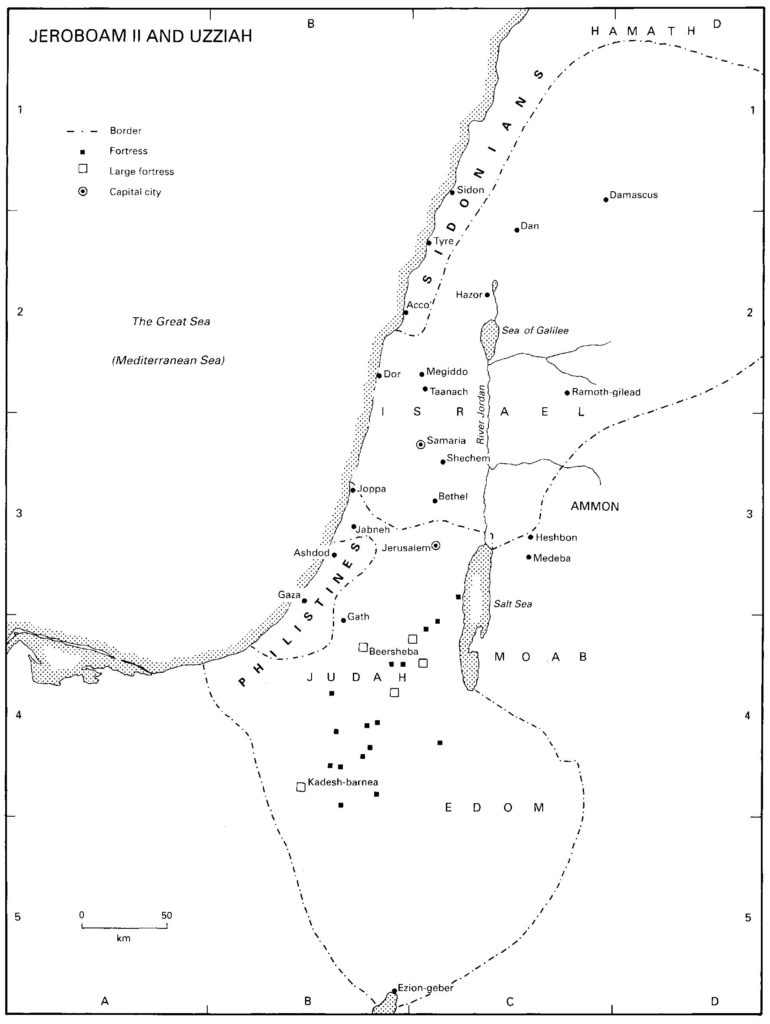

Map 1: Jeroboam II and Uzziah: background 2 Chronicles 26&27 produced from the Atlas of Jewish History, (Dan Cohn-Sherbok, 1994), 26

| 747-745 |

Assyria. Pul ascends throne 745* |

2 Kings 15. In those days (Jotham) the LORD began to send against Judah Rezin the king of Syria, and Pekah the son of Remaliah (v. 37) |

2 Chron 27.

Jotham subjugates Transjordan. (Ammonites) pay tribute 3 years.(v. 5) |

| 744/743* |

Assyria. Anti-Assyrian coalition formed under the leadership of Urartu, Arpad, and Cicilian states, a coalition that included Rezin of Damascus and Hiram of Tyre. [51] Siege of Arpad begins. |

2 Chron 28. Ahaz becomes co-regent (v.1); {743/4, Perry} |

Isaiah 7. In days of Ahaz…(v.1) |

| 742-740* |

Assyria. The Assyrian sources contain no evidence of Tiglath-Pileser’s arrival in the land of Israel in the time of Menahem, but the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser are silent regarding events during the years 742-740, and therefore the Biblical testimony is not to be rejected out of hand.[52] Arpad conquered and annexed as first full province of Syria. (740*) |

2 Chron 28. Judah delivered to Syria AND ALSO to Pekah (v. 5). |

Isaiah 7. Invasion (s) by Pekah and by Rezin; Jerusalem not conquered (v.1) |

| 742-740* |

2 Chron 28. Spoil and captives taken to Samaria; a remnant sent back under instructions of the prophet Oded. (vv. 8-15) |

Isaiah 7. Remnant Returns = Shear-jashub (v. 3) |

| 740/739 |

Assyria. Isaiah advises against Assyrian coalition: Immanuel (=Hezekiah born) |

2 Kings 15.

Pul in the land. (vv. 19-20) |

2 Chron 28. Ahaz sends for help to Pul (v. 16); Edomites and Philistines invade (vv. 17-18) Pul in the land distress for Ahaz (v. 20); Ahaz sacrifices to gods of Syria (v. 23 cf. v.2 Baalim)

|

Isaiah 7. Prophetic warning: Philistia=Fly and Assyria=bee (v. 18) Maher-shalal-hash-baz= (Assyrians) quick to plunder, swift to prey (8:1)

|

| 739* |

Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser leaves the region: north Syrian states again rebelled against Assyria, this time under the leadership of Tutammu, the king of Unqi, whose capital was Kullani. |

| 738* |

Assyria. Iran Stela; The Assyrian army returns to suppresses the coalition, and receives tribute from the rulers as far south as Rezin of Damscus, Hiram of Tyre, Menahem of Israel, and Zabibe the queen of Arabia[53] |

2 Kings 15. Menahem pays tribute (vv.19-20) and dies in this year (Perry)

|

|

736-735* SYRO-EPHRAIMITIC WAR Assyria. An alliance of Hiram, ruler of Tyre and Rezin of Damascus. Also, one known as Mitini of Ashkelon broke his oath of allegiance to Assyria. Tiglath-Pileser moves against Philistia to quell the rebellion then returns home. Eponym Chronicle: According to the timing of the chronicle there ended up being a series of campaigns that began in Philistia and subsequently continued through to Damascus in the years 733-732. This would show that the conquering of Damascus was completed in 732/731 for the Chronicle has Tiglath-Pileser in Sapia in southern Babylon in 73l/730)[54] |

2 Kings 15. Pekah conspires against Pekahiah (Menahem’s successor) supported by Gileadites (v.25) Pekah commences in 52nd year of Uzziah and rules 20 years (v.27) |

2 Kings 16.

Pekah and Rezin besiege Ahaz (v.5) Syrians recover Elath (v.6)

|

Isaiah 7. Rezin and Pekah now confederate as predicted by Isaiah (v.2) |

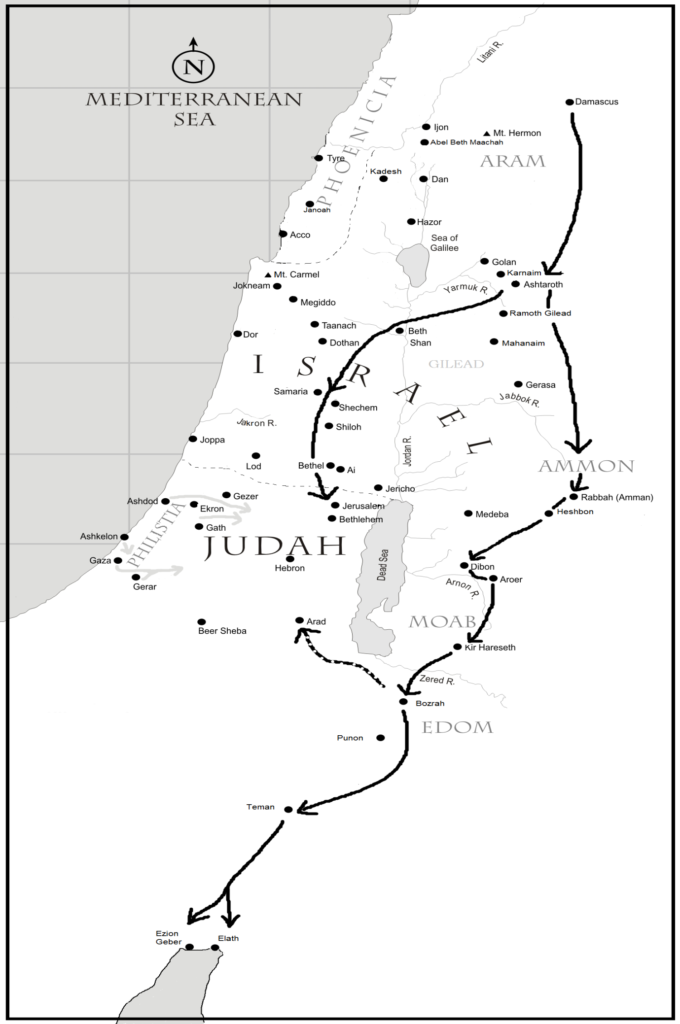

Map 2: is the Syro-Ephraimitic war 735/736 (not to scale) background 2 Kings 16

| 729/8* |

Assyria. In the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser, Ahaz is mentioned by name only in a clay inscription from Calah (K 3751 Tadmor, ITP, Summ. 7, rev., 1.11′ , in which “Jehoahaz of Judah” is listed among those presenting tribute to Assyria, along with other kings, including those of Ammon, Moab, and Edom, and the Philistine kings: [Mi]tind of Ashkelon and [Ha] nun of Gaza. This summary inscription was composed after the seventeenth year of Tiglath-Pileser III ( 729/8).[55] |

2 Kings 16. Ahaz requests Assyrian help, pays tribute(v.7) |

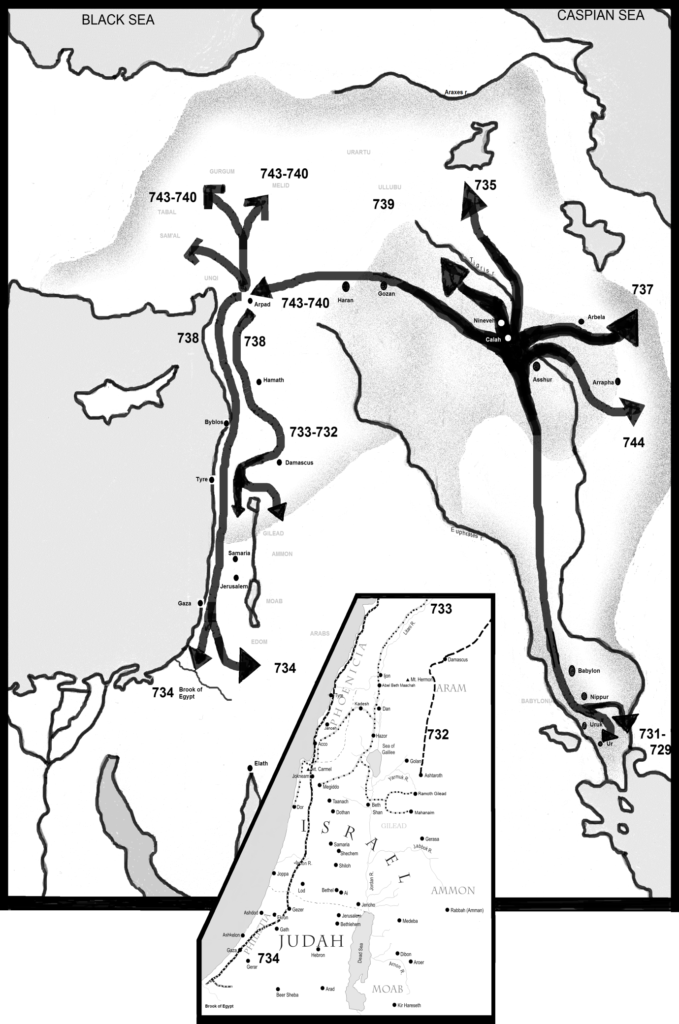

Map 3: Assyrian campaigns of Tiglath-Pileser III (not to scale) for the period 744-732, background 2 Kings 15&16; 2 Chronicles 28 and Isaiah 7, is an amalgam from The Times Concise Atlas of the Bible (Harper Collins, 1991), and the inset (not to scale) is produced with help from Nelsons Complete Book of Bible Maps & Charts, (Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville. TN); Holman QuickSource Bible Atlas, (Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, TN)

|

733-731* Assyria. The Eponym chronicle highlights Tiglath-Pileser’s campaigns into the Damascus. The first conquest relates to that of Damascus. Tiglath-Pileser spends much time in his summary inscription to his defeat of Rezin.[56] Assyrian king decides to shorten his time in Urartu, lift the siege on Tushpa, and direct his forces to the west in order to halt the erosion of the Assyrian position and prevent the expansion of the Aramean-Israelite coalition.[57] Annals 23; Rezin ultimately falls after a prolonged siege into the regnal year 732/731 and is killed.[58] |

2 Kings 15. In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took Ijon, and Abelbethmaachah, and Janoah, and Kedesh, and Hazor, and Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and carried them captive to Assyria. (v. 29) |

2 Kings 16. Pul assists and destroys coalition (v. 9) Ahaz meets Pul in Damascus and copies Assyrian altar (v. 10). Judah now an Assyrian vassal |

Isaiah 7

There are four possibilities for of translating the name ‘Shear-jashub’ (excluding emending the text):

- a remnant indeed shall repent (turn to YHWH);

- a remnant indeed shall return (survive);

- only a remnant shall repent or turn to YHWH;

- only a remnant shall return or survive.[59]

It has been suggested in this article that this “remnant” are the Judean captives sent back at the urging of the prophet Oded, however, J. Day and R. Clements apply the name to the Syrian and Ephraimite survivors of the Assyrian invasion. This seems unlikely as the Immanuel prophecy was directed at the house of David and one assumes that the presence of Shear-jashub had immediate relevance to Ahaz. The prophetic name Shear-jashub is not explained in Isaiah 7 and probably had more than one application as Isa 10:20-23 speaks of an Israelite remnant turning to the “mighty God”; this is the title employed for the “child” in Isa 9:6 who will sit on the Davidic throne (v. 7). These were the faithful remnant who responded to the “great light” (v. 2) of the Hezekiah reformation. There is possibly a further application to Sennacherib, as he boasted of taking more than 200,000 captives and no doubt a remnant was released and returned to the land when the Assyrian army was defeated outside of Jerusalem during Hezekiah’s reign. The chiastic structure of Isaiah 7-9 climaxes with revealing Immanuel as the royal Son,[60] who shines light into the shadow of death:

| A | Historical prologue (7:1-2) | ||||

| B | In the presence of Shear-jashub (7:3) | ||||

| C | Judgment on Aram and Israel (7:4-9) | ||||

| D | The sign of Immanuel (7:10-16). | ||||

| E | In the shadow of Assyria (7:20-25) | ||||

| A | Historical prologue (8:1-2) | ||||

| B | The sign of Maher-shalal-hash-baz (8:3-4) | ||||

| C | Judgment on Judah (8:5-8) | ||||

| D | Lament of Immanuel (8:8-10) | ||||

| E | In the shadow of Yahweh (8:11-15) | ||||

| A | A call to repentance (8:16-17) | ||||

| B | The sign of Isaiah’s children (8:18) | ||||

| C | In the shadow of judgment (8:19-22) | ||||

| D | Out of the shadow of death and into the light (9:1-5) | ||||

| E | The Royal Son (9:6-7) | ||||

The sign offered to Ahaz is regarded by many scholars as a merismus – “in the depth or the height above” (v. 11), in other words the two contrasting extremes are made to stand for the whole – ask for anything in heaven and earth. However, in Gen 49:22-26, the blessings of the deep and of the heavens is messianically associated with fecundity and progeny. In Isa 45:8 a similar idiom is employed with the heavens pictured as pouring down righteousness and the earth opening up to reveal righteousness. The context there is “concerning my sons” (v. 11), particularly, calling by name (vv. 3-4). The Fourth Gospel alludes to the prophecy in Isaiah 7 (earthly things/heavenly things; John 3:12) in the context of being “born from above” with Nicodemus recognising (John 3:2) that Jesus has “God with him” (=Immanuel). Furthermore, the question of origins and legitimacy looms large in the gospel as no one knows where the wind originates or where it is going; so it is with the man of the spirit (John 3:8). Christ’s legitimacy and his origins are questioned throughout the gospel – Jesus’ origins are unknown (born from above) as is his destiny (resurrection from the earth). Thus, both heaven and earth are involved in the messianic sign; the depth and the height. It is therefore not unreasonable to seek the initial fulfilment of the prophecy in Hezekiah who as the “suffering servant” of Isaiah 53 was raised from his death bed on the third day. In this sense Hezekiah signified the depth…. “I said in the cutting off of my days, I shall go to the gates of the grave: I am deprived of the residue of my years” (Isa 38:10). His “resurrection” from the depth was a sign but his birth was also a messianic sign.

The birth of Immanuel was not a miraculous “virgin birth”; it was, however, a supernatural messianic sign. Much debate has raged around the Hebrew hml[ (`almâ); does it mean, 1) virgin, young woman 1a) of marriageable age 1b) maid or newly married? In the original prophetic context, the solution must be sought in one of Ahaz’s wives or concubines, a newly married young virgin who was not even aware that she was pregnant! This new mother would name her child Immanuel,[61] and presumably the news of the unexpected birth reached Ahaz shortly after the prophecy was issued.

The “miracle” of the “virgin birth” in Isaiah’s time was the completely unexpected nature of the birth and the fact that divine foreknowledge predicted in advance what was about to happen (Ahaz had no knowledge of the pregnancy and neither did the mother until the delivery!); “Thus saith the Lord, the Holy One of Israel, and his Maker, ‘Ask me of things to come concerning my sons, and concerning the work of my hands command ye me’” (Isa 5:11).

The mother of Hezekiah was Abijah (2 Chron 29:1), which means Yah is my Father and is an obvious reference to the messianic promise of 2 Sam 7:14 “I will be his father, and he shall be my son”. Hezekiah became the “son” of Yahweh and the (suffering) “servant” of Yahweh in contrast with Ahaz who appealed to Tiglath-Pileser III with the words; “I am thy servant and thy son: come up, and save me” (2 Kgs 16:7). Ahaz was wont to “pass his sons through the fire” (2 Kgs 16:3 cf. Mic 6:7) and this prophecy stood as a warning (not to touch the child) and a promise (that the Davidic dynasty would be established through Immanuel).

The name Immanuel should be understood as an epithet or cognomen (cf. Isa 45:5; “surname”) the name Hezekiah means Yah strengthens. Both of his names are played on in 2 Chron 32:8; “With him is an arm of flesh; but with us is the Lord our God (= Immanuel), to help us and to fight our battles.” And the people were strengthened by the words of Hezekiah (= Yah strengthens) king of Judah.” This in itself indicates that Hezekiah and Immanuel is the same person.[62]

Before this Immanuel child was old enough to choose between right or wrong[63] the land would be desolate and both Syria and Ephraim defeated by Assyria. Cultivated land would be overtaken by wild growth and cattle would graze freely in the bush. People would need to take a bow and arrow with them when they went out in the field (for the wild animals) but the wild vegetation would provide fodder for cattle, with the wild flowers producing abundant pollen for the honey bees. As a consequence, the child would eat plenty of butter, yoghurt and honey, usually luxury items.

Within sixty-five years Ephraim would be too shattered to be a people (Isa 7:8). Most scholars believe that the prophecy was given during the Syro-Ephraimitic war (735/736) with Samaria destroyed some 12 or 13 years after this oracle (721/722) rather than 65 years later. The most common interpretation of this text is that the phrase in v. 8b was a marginal note merged with the text or a gloss (65 years may refer to the deportations brought about by Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in about 670/69 BCE)[64] Various other suggestions have been made to resolve this problem: Whittaker[65] follows a reading similar to that suggested by the Jerusalem Bible which translates this phrase as “Six or five years more”, but this sequence of numbers would be unique and the manuscripts of the MT do not reveal any variations of the sequence. E. J. Kissane suggests, “Yet six, nay, five years more …”.[66] However, this article argues that the prophecy was given earlier (circa 740), even so, it does not compute to a 65-year period. It is suggested that the solution should be sought by reckoning retroactively from the beginning of Uzziah’s monarchy. Uzziah was the stabilising feature during this whole period of overlapping co-regencies, and Isaiah commenced his ministry during his reign. From the beginning of Uzziah’s monarchy until the fall of Samaria is 65 years and this is essentially the position that Lightfoot holds.[67]

Isaiah’s son not Immanuel

It is often suggested that Immanuel is one of Isaiah’s sons, possibly even Maher-shalal-hash-baz. This actually raises more problems than it solves; If, (a) hml[ (`almâ) refers to a young woman up to the birth of her first child the she could not be Shear-jashub’s mother; one must assume instead that through death or some other circumstance Isaiah was about to marry another woman: and (b) none of the traditions suggest that Isaiah names this child, whereas he had given the sign-names of his other children. Some scholars suggest that Maher-shalal-hash-baz and Immanuel are the same person but in 8:3 his mother is called “the prophetess” not the hml[ (`almâ), furthermore, Maher-shalal-hash-baz would have two prophetic names.

Isaiah’s second son, Maher-shalal-hash-baz (Isa 8:3), is introduced without preamble in Isa 8:1 and this is understood as implying that “he was retrospectively known to be a fulfilment of the Immanuel prophecy”.[68] However, this is overstating the case as the conception notice in Isa 8:3 is prescient and somewhat parenthetical; it is written from the point of view of an omniscient narrator. The conclusion of the matter is given first (the birth of a son) but this is (obviously) after the matter is recorded and witnessed. Therefore, the order of events is; (1) Isaiah, write concerning swift is booty, speedy is prey. [8.1] then, (2) Isaiah gathers witnesses [8:2] then, (3) Isaiah writes verses 4-22 concerning Assyrian destruction, then; (4) Isaiah has relations with his wife (the prophetess not the virgin) and she conceives another son (besides Shear-jashub) who is called Maher-shalal-hash-baz.

This is the only possible order, as it was important to record and witness the “sign” in advance of his wife conceiving in order to establish both the time-frame and the prophetic credentials of the sign. Perry notes that Isaiah mentions Immanuel (God with us) in 8:8 and deconstructs his name in 8:10 and therefore associates Immanuel with his disciples in 8:16 who probably took Immanuel to the royal court to demonstrate the fulfilment of the “sign”. Firstly, the mention of Immanuel in the “spoil” prophecy is not unusual as he was introduced in the previous chapter. Secondly, an association with Isaiah’s disciples is not unusual as one of the “witnesses” to the prophecy was Hezekiah’s maternal grandfather (Zechariah, 2 Chron 29:1 and Isa 8:2)[69]. Thirdly, it would be unnecessary to take him into the royal presence, as the young child Hezekiah would already reside at the royal court with his mother as a permanent reminder and “sign”.

Summary

This article has prosecuted the case that Hezekiah is Immanuel. The chronological problem surrounding his birth has been resolved, with the year 740 suggested as his birth year. The period 742-740 is proposed as the time when the incursions of 2 Chronicles 28 (by Ephraim and Aram) against Judea occurred; this was a continuation of hostilities that commenced in the days of Jotham. This was a period of rebellion against Assyria and an opportunity for Pekah and Rezin to recapture the trade routes. During this period, Judea’s neighbours, Philistia and Edom, took advantage of Ahaz’s weakened state and also launched raiding parties. The Assyrian records are silent on the events at this point but the Biblical record does suggest a visit by Assyria to the land. When Tiglath-Pileser III sent a delegation into the region Pekah and Rezin submitted to Assyria (together with Menahem) and they resolved to pay tribute. It is at this point that Isaiah delivers the Immanuel prophecy with the child born almost immediately after his words were spoken (ca. 740) as a sign, with an implicit warning that Assyria cannot be relied on. It seems that Pekah and Rezin (and probably Menahem) made the case before Tiglath-Pileser III that they could not raise enough revenue until the trade routes were liberated from Judean control. Despite the warning from Isaiah a “bribe” was offered by Ahaz, however, Assyria decided that it was commercially more advantageous to support its vassal states against Judea (he struck Ahaz a blow). As yet, Ahaz was still “neutral” and had not become a vassal state and Assyrian self-interest determined to resolve the dispute in favour of its (unruly) vassals. After the Assyrians left the region, Ephraim and Aram decided to formalise their coalition and drive their advantage home by replacing Ahaz with a puppet king who would do their bidding. Whether or not this was an anti-Assyrian move or not is debatable but it was perceived as unacceptable by Assyria as it would grant Israel and Aram too much regional power. Thus, when the Syro-Ephraimitic war was launched in a coordinated fashion in 735/6, Assyria decided to break the regional coalition and accepted the appeal by Ahaz to become a vassal (Judea became a buffer state on the Egyptian border). Hezekiah would have been about 5-6 years old at the commencement of renewed hostilities (735/6) and about 9-10 years old by the time the coalition was defeated (731/2), thus fulfilling the terms of the Immanuel prophecy. Of course, much of this scenario is of necessity speculative but any reconstruction must address the lacunae in both the biblical records and the Assyrian inscriptions. Historically speaking, both sets of records should be given equal weight and the biblical records should not be dismissed as theologically motivated in contrast with the unbiased (sic) Assyrian accounts. Moreover, whereas the Biblical records are interested in events in Judea, the Assyrian records only mention Ahaz incidentally as a vassal, probably as late as 729. This text is the only reference to Judah in the Assyrian inscriptions prior to 720. Judah was therefore relatively unimportant in the larger scheme of Assyrian politics.

Conclusion

Immanuel is Hezekiah, the wonderful counsellor, prince of peace and mighty God, but also the suffering servant – the one called by name from the womb – the one who foreshadowed the Messiah.

[1] H. A. Whittaker, Isaiah (Cannock: Biblia, 1988), 149.

[2] J. Edmund, Identity and Function within the Bookend Structure of Proto-Isaiah (Anderson University of Pretoria, 2008), 138. See also J. McHugh, “The Date of Hezekiah’s Birth” VT 14:4 (1964): 446-453.

[3] G. Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1996), 98-107 (101).

[4] For example, G. R. Driver explains the unusual MT construct in 1 Sam.13:1 as a misreading of alpha-numeric values k (20) as b (2). G. R. Driver, “Abbreviations in the Masoretic Text” Textus 1 (1960): 112-131 (126f); Textus 4 (1964): 76-94 (83).

[5] S. Gandz, “Hebrew Numerals” Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 4 (1932-1933): 53-112 (pp. 58, 68). Table II presents evidence from ostraca and ossuaries.

[6] H. L. Allrick, “The Lists of Zerubbabel (Nehemiah 7 and Ezra 2) and the Hebrew Numerical Notation” BASOR 136 (1954): 21-27 (24).

[7] J. W. Wenham, “Large Numbers in the Old Testament” Tyn. B. 18 (1967): 19-53 (Online, p. 6).

[8] Reproduced from Wikipedia [Jan 2015] ‘Hezekiah’ entry (with footnotes corrected).

[9] W. J. Murnane, Ancient Egyptian Coregencies (Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 1977) and J. D. Douglas, ed., New Bible Dictionary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1965), p. 1160.

[10] N. Na’aman, “Historical and Chronological Notes on the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the Eighth Century BC” Vetus Testamentum 36 (1986): 71-92 (91).

[11] See Kitchen’s chronology in New Bible Dictionary p. 220.

[12] L. McFall, “A Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles” Bibliotheca Sacra 148 (1991): 3-45 (42).

[13] J. Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (rev. ed.; Peabody MA: Hendrickson, 1998), 246.

[14] McFall, “Translation Guide”, 44-45.

[15] Available www.christadelphian-ejbi.org/presentations/Kings_Chronology.xlsx [Ed AP]: Sadly, L. McFall died last year, but we had the opportunity to discuss chronology with him at a SOTS conference a few years back.

[16] A. Perry, “Who is Immanuel?” CeJBI 5/2 (2011): 62-68 (64).

[17] When Ahaz submitted to Pul in Damascus he paid obeisance to the Assyrian gods as proof of his subjection. It is obvious that Pul had an Assyrian altar installed in Damascus as attestation to the supremacy of Assur over Baal. It was this altar that Ahaz copied.

[18] Although 2 Chronicles 28 does not mention Jerusalem as the objective, Isa 7:1 adds a preposition (with a feminine personal pronoun), indicating that the object of the attack was Jerusalem herself. The context of 2 Chronicles 28 shows Ahaz shut up in the city while the land is raided and ravished by Syrians, Israelites, Philistines and Edomites.

[19] Maaseiah was probably the son of Jotham and brother to Ahaz. Maaseiah may have been heir to the throne.

[20] H. Cazelles, “Problèmes de la guerre Syro–Ephraimite” Eretz-Israel 14 (1978): 70-78 (72).

[21] Shear-jashub appears to be an integral part of the message since Isaiah is commanded to bring him – H. Wildberger, Jesaja 1-12 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1991), 277-279; R. E. Clements, Isaiah 1-39 (NCB; London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 1980), 83; O. Kaiser, Isaiah 1-12 (OTL; 2nd ed.; London: SCM Press, 1983), 140.

[22] P. S. Evans – “Dialogism in the Chronicler’s Ahaz Narrative” Draft for discussion at the 2008 Bakhtin and the Biblical Imagination Seminar, p.20. Evans understands Isaiah 7 as conducting a “dialogue” with 2 Chronicles 28. [Available Online.]

[23] Several versions read the “Edomites” as “Arameans” and suggest that Damascus had previously held the Judean city of Elath and Rezin recaptured it. The MT Kethib and some manuscripts of the Syriac, Targum, and Vulgate presuppose the Hebrew ~ymra (“Arameans”). By contrast, the MT Qere, LXX, and other manuscripts of the Targum and Vulgate presuppose ~ymda (“Edomites”). Some scholars, (J. Gray and G. H. Jones) remove Rezin as a gloss and read “Edom” (~da)) for “Aram” (~ra) throughout the verse. S. A. Irvine, Isaiah, Ahaz, and the Syro-Ephraimitic Crisis (SBL Dissertation Series 123; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), 84-85, however, argues on the basis of the historical evidence for Syria’s prominence at this time that Rezin may be original and that he may have aided the Edomites in taking Elath at this time.

[24] A. Alt, „Hosea 5-8 – 6-6. Ein Krieg und seine Folgen in prophetischer Beleuchtung“ Neue kirchliche Zeitschrift (1919): 537-68. One of the main reasons for this view is that the order of the cities listed appears to form a line moving northward toward Samaria from the area of Jerusalem. So also J. L. Mays, Hosea (London: SCM Press, 1969), 85-89; J. Jeremias, Der Prophet Hosea (Berlin: Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, 1983), 80-82; H. W. Wolff, Hosea (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1974), 103-30.

[25] P. Arnold, Gibeah: The Search for a Biblical City (JSOTSup 79; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1990), 112-15.

[26] There is no consensus regarding the date of this text, but it appears to predate the Iran Stela, which is more securely dated to 739-738. For a full discussion on dating, see J. K. Kuan, Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions (Hong Kong: Alliance Bible Seminary, 1995), 141.

[27] See H. Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994), 276.

[28] For the original publication, see T. Levine, Two Neo-Assyrian Stelae from Iran (Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, 1972). For a complete reading of the stela, see Tadmor, Inscriptions, 91- 110.

[29] The text must precede Layard 50a+50b+67a because that text names Hiram as the king of Tyre. See also the Mila Mergi Rock Relief and the Eponym Chronicle, Kuan dates the text to 739 -738 (Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions, 151) while Levine dates it to the 737 campaign to Media (Two Neo-Assyrian Stelae, 14).

[30] See T. Levine, “Menahem and Tiglath-Pileser; A New Synchronism,” BASOR 206 (1972): 40-42.

[31] For discussion of dating, see Stuart A. Irvine, Isaiah, Ahaz, and the Syro-Ephraimite Crisis (SBLDS 123; Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1990), 40-44.

[32] For example, Tadmor reconstructs “Bit-[Humri]” but allows that “Bit-[Hazael]” is possible (Inscriptions, 80-81).

[33] See ibid, 202-3.

[34] For discussion, see H. Tadmor, “The Southern Border of Aram” IEJ 12 (1962): 114-122 (116), and Kuan, Neo-Assyrian Historical Inscriptions, 177.

[35] For the original publication, see D. J. Wiseman. “A Fragmentary Inscription of Tiglath-Pileser III from Nimrud” Iraq 18 (1956): 117-129.

[36] Perry, ‘Kings Chronology’ is used for dating the Israelite and Judean kings

[37] E. R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (3rd ed.; Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan/Kregel, 1983), 129-134, (217), following H. J. Cook, “Pekah,” Vetus Testamentum 14 (1964): 121-135, and C. Lederer, (Die biblische Zeitrechnung vom Auszuge aus Ägypten bis zum Beginne der babylonischen Gefangenschaft, 1887, (cited in Cook, Pekah 126, n. 1.), holds that Pekah set up in Gilead a rival reign to Menahem’s Samaria-based kingdom in Nisan of 752 BC, becoming sole ruler on his assassination of Menahem’s son Pekahiah in 740/739 BC (736, Perry) and dying, according to Thiele, in 732/731 BC.

[38] Pekah’s coup against Menahem’s successor was supported by Gileadites (2 Kgs 15:25).

[39] G. Galil, “A New Look at the Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III” Biblica 81 (2000): 511-520 (512). [Available Online.]

[40] G. Galil, ‘Conflicts Between Assyrian Vassals (Haifa)’, presented at the 39th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale (“Assyrien im Wandel der Zeiten”) in Heidelberg in July 1992. [Available Online.]

[41] J. Begrich, „Der syrish-ephraimitische Krieg und seine weltpolitischen Susammenhänge“ ZDMG 83 (1927): 213-237.

[42] For a summary of the positions see, T. D. Finlay, The Birth Report Genre in the Hebrew Bible (Mohr Siebeck, 2005), 174-175, and Kelle, Hosea 2: Metaphor and Rhetoric in Historical Perspective, 187-190.

[43] B. Oded, “The Historical Background of the Syro-Ephraimite War Reconsidered” CBQ 34 (1972): 153-165 (154). K. Budde, “Jesaja und Ahaz” ZDMG 84 (1931): 125-38, had also earlier argued at length against Begrich’s view.

[44] Oded, “The Historical Background of the Syro-Ephraimite War Reconsidered”, 155-61.

[45] Obed, “The Historical Background of the Syro-Ephraimite War Reconsidered”, 151-154.

[46] R. Tomes, “The Reason for the Syro-Ephraimitic War” JSOT 59 (1993): 55-71: (61, 64-65).

[47] Edmund, Identity and Function within the Bookend Structure of Proto-Isaiah, 140.

[48] A. K. Laina, ‘The Use of Biblical and Extra-Biblical Texts in Historiography: An Analysis of the Syro-Ephraimitic Crisis’ (Course submission to DOT, Younger, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 2003), 9. [Available online.]

[49] Galil, “A New Look at the Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III”, 516-517.

[50] Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah, 68.

[51] H. Cazelles, ‘Syro-Ephraimite War’ (ABD 6, New York: Doubleday, 1992), 282-285 (284).

[52] Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah, 64.

[53] Irvine, Isaiah, 25- Note; Phoenicia, Philistia, the lands east of the Jordan, and Judah is not mentioned in the List of tribute-givers in 738

[54] Irvine, Isaiah, Ahaz, and the Syro-Ephraimitic Crisis, 25. A. Rainey, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 230, provides a summary of the main narrative of the military action in Philistia with some minor conjectures.

[55] Galil, The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah, 67.

[56] Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III, King of Assyria, 23:1’-17’.

[57] Galil, “A New Look at the Inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser III”, 519.

[58] Irvine, Isaiah, Ahaz, and the Syro-Ephraimite Crisis, 30.

[59] This scheme of four possibilities is laid out by S. lrvine in “Isaiah’s She’ar-Yashub and the Davidic House” BZ 37(1993): 79.

[60] [Ed AP]: This doesn’t look like a chiastic structure as the corresponding letters have different topics assigned. It is perfectly possible to hold that Immanuel is not Hezekiah and that that the royal son of Isa 9:6 is Hezekiah.

[61] In contrast with the MT variants the LXX has Ahaz being instructed to name the child, this is highly unlikely considering his unfaithfulness.

[62] For scholars that interpret Immanuel as Hezekiah, see Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 43:8; 48:7; 71:3; 77:1; J. Klausner, The Messianic Idea (New York: Macmillan, 1955), 56f.; H. Wildberger, Isaiah 1-12 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1991), 291, (son of Ahaz, perhaps Hezekiah); H. A. Whittaker & G. Booker, Hezekiah the Great, (Birmingham: CMPA,1985); Whittaker, Isaiah; and Edmund, Identity and Function within the Bookend Structure of Proto-Isaiah.

[63] This probably refers to becoming a “son of the commandment” (Bar Mitzvah) when the child, aged 12, became legally responsible.

[64] See J. Skinner, Isaiah Chapters I-XXXIX (ICC; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1896), 54; G. B. Gray, Isaiah I-XXXIX (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1912), 119f.; Clements, Isaiah 1-39, 85; Kaiser, Isaiah 1-12, 136f.; J. Ridderbos, Isaiah, (Grand Rapids; Zondervan, 1985), 83. See specifically 2 Chron 33:11; Ezra 4:2, 10 which speak of a later deportation by Esarhaddon (669 BCE) and may suggest that Israel had some national existence after the destruction of Samaria in 722 BCE (ANET, 290f.).

[65] Whittaker follows the suggestion by W.A. Wordsworth (“within six, even five years”) in Isaiah, 146.

[66] E. J. Kissane, Isaiah (2 vols.; Dublin: Browne & Nolan, 1960), 1.78f., 82

[67] J. Lightfoot, The Whole Works of the Rev. John Lightfoot: Master of Catharine Hall, Cambridge, Volume 2, (ed., John Rogers Pitman, J.F. Dove, 1822: Digitized 23 Jun 2010), 244. [Available online.]

[68] See Perry, “Who is Immanuel?”, 62-68 (65).

[69] Zechariah was possibly the deputy high priest; Isaiah was probably also a priest. Zechariah (Yah has remembered his covenant) was faithful as was his daughter Abijah (Yah is Father)