N. T. Wright opens his exegesis of Col 1:15-20 by saying the passage “exhibits a characteristically Pauline form of what we may call christological monotheism”.[1] His exegesis takes the line that the passage expresses a Wisdom Christology. The claim is an important positioning statement because Wright wants to include Christ within the Jewish monotheistic framework of Paul’s thought in such a way as to allow a Trinitarian development. At the conclusion of his study of the passage, he says,

“It is now, I believe, necessary to assert that, although the writers of the New Testament did not themselves formulate the doctrine of the Trinity, they bequeathed to their successors a manner of speaking and writing about God which made it, or something very like it, almost inevitable.”[2]

We will examine Wright’s essay on Col 1:15-20. We have two questions: first, whether Col 1:15-20 is that particularly monotheistic let alone whether it exhibits ‘christological monotheism’; and secondly, whether it expresses a Wisdom Christology and teaches the pre-existence of Christ in the person of the Son (v. 13).

We take the text in its final form. Hence, there are many issues we leave to one side such as authorship (we take it to be by Paul); composition (we take it to be all from the hand of Paul); and literary form (we take it to be poetic in structure and maybe a hymn). We are interested in just its intertextual links with the Jewish Scriptures and other NT writings.[3]

We have divided the article into two sections: the first (Section A) is a straightforward exegesis assuming no more about the ‘powers’ of v. 16 than that they are powers in the heavens and on earth. The second (Section B) is a discussion of the traditional topic of the ‘principalities and powers’ of v. 16.

Section A

Introduction

J. D. G. Dunn opens his discussion of Col 1:15-20 as follows:

The basic movement of thought also seems clear enough – from Christ’s (pre-existent) role in creation (first strophe) to his role in redemption (second strophe), from his relationship with the old creation (protology) to his relationship with the new (eschatology). But whether these first impressions are wholly accurate will depend on what our exegesis of the main clauses and concepts reveals.[4]

Dunn’s remark is useful. First impressions are set by our prior assimilation of church doctrine which guides our initial reading. This, however, breaks down upon analysis. The first strophe (vv. 15-18b) does not presuppose pre-existence because it is not about any act(s) relating to the Genesis creation on the part of the Son; it is about Christ’s status vis-à-vis creation as Paul sees it in his day. The second strophe (vv. 18c-20) mentions the new creation, but we shouldn’t take this and read the new creation back into the first strophe – we should maintain a distinction between comments about all of creation and comments about the new creation of men and women in Christ.

Analysis

Commentators spend some time discussing the form of the passage, pointing out its parallel structures and poetic nature.[5] There are some alternative analyses on offer, depending on what common vocabulary and grammatical structures the commentator wants to emphasize.[6] In addition, some commentators are wont to speculate about earlier forms of the passage, conceived as a hymn, and about interpolations that disrupt a smooth parallel structure. All of this is of no concern to us,[7] because as repeated readers of the passage, we can easily see connections criss-crossing across the passage and it doesn’t matter whether we emphasize one rather than another, as long as we see them all in time and give each some attention. Our interest is in what the passage teaches us today about Christ using an intertextual method.

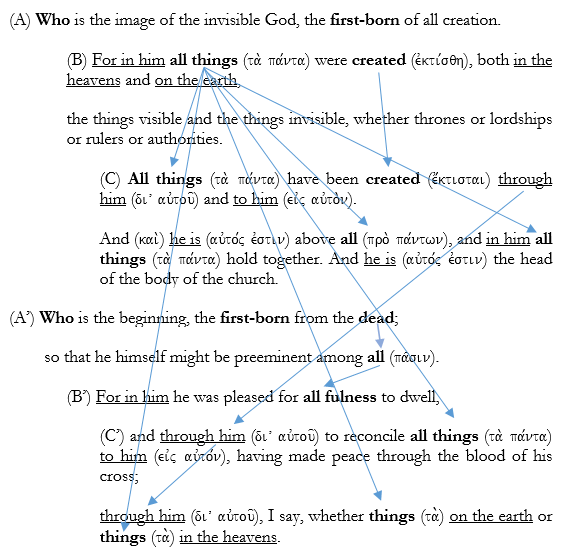

We have set out a commonly proposed structure of the poem in English below. This is not particularly controversial; it’s a little literal in how it renders the prepositions, but it largely copies that of Wright.[8] The main point to make is that the second (A’) clause gives the basis for the first (A) clause.[9] Christ is pre-eminent among all and this is his status as the firstborn of all creation; but this is based on his being the firstborn from the dead.

The clause (B’) is parallel to (B) and stipulates a second aspect of what is ‘in Christ’, namely, ‘all fulness’. This is defined in Col 2:9, “For in him dwelleth all the fulness of the Godhead bodily.” This fulness is not singular in Christ but in the body with Christ. The ‘all things’ of (B) is specified as ‘thrones or lordships or rulers or authorities’, but the ‘body of the church’ is added in a refrain at the end of (C).

Clause (C) states again that all things have been created, but adds ‘through him’ and ‘to him’. This corresponds to (C’) where ‘to reconcile’ is the verb associated with ‘through him’ and ‘to him’. From this temple-motif of all fulness dwelling in Christ and his body, God goes out and reconciles all things to him.

The Col 1:15-20 passage is made up of two paragraphs (vv. 15-18a and vv. 18b-20), set out above.[10] This paragraph structure is constructed around the relative pronouns which all relate to the mention of the Son in v. 13:

…his dear Son, in whom we have… (v. 14) …who is the image… (vv. 15-18a) … who is the beginning… (vv. 18b-20)

The second paragraph (vv. 18b-20) uses various expressions from the first paragraph (vv. 15-18a), thereby adding supplementary information to the first paragraph.

The analysis is straightforward but it throws up these puzzles for us:

- What are the powers? Are they civil, religious and earthly? Are they angelic, demonic and heavenly? Are they forces in society? Are some of the four terms earthly and some heavenly?

- If the new creation concerns a body, the church, why is there talk of thrones, lordships, rulers and authorities?

- When were the powers created? Relative to Paul, are they of the past, the present or the future?

The analysis is fairly mainstream; there is nothing in the Greek that concerns us; we translate the Greek prepositions consistently so that their use can be compared across the clauses. It should be clear from the way we have set out the text that the passage reads straightforwardly as an ‘all creation’ description, but that the mention of thrones, lordships, rulers and authorities along with the ‘body of the church’ is puzzling.

Creation

There are obvious allusions to creation in Col 1:15-20, but there are also echoes of the exodus in vv. 12-13: the children of Israel were delivered from the power of darkness (Egypt; Exod 10:23); they were redeemed through the blood of the firstborn of Egypt (Isa 43:3) and transferred to the promised land; and they saw light in the face of Moses who had been in the presence of the invisible God.[11]

The teaching about the Son (vv. 13, 15) is an Adamic typology: quoting Gen 1:27 (not v. 26), he is ‘the image’[12] of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. Were this a literal (and temporal) statement about the Genesis creation, it would be false because Adam would be the ‘firstborn’ of that creation. Moreover, it is not a statement about any time before the Genesis Creation, such as the beginning of the universe,[13] because the Genesis Creation introduces the birth-death framework for human beings, and it is only in this framework that ‘firstborn’ makes sense (both literally and as a metaphor). The statement cannot therefore be about any pre-existence of the Son. Hence, it follows that the title ‘firstborn of all creation’ is about the position and status of the Son as the firstborn of all creation at that time.[14]

The parallelism between v. 18b, ‘firstborn from the dead’ and v. 15b, ‘firstborn of all creation’ is not an equivalence; it is a causal relationship: Christ is the firstborn of all creation because he is firstborn from the dead, but ‘firstborn of all creation’ is a title of the position of the Son as a king. This is shown by the logic, ‘firstborn from the dead in order that (i[na) he might have pre-eminence among all things’.[15]

Paul has referred to Christ as God’s ‘dear Son’ or ‘the son of his love’ (v. 13). This picks up on God’s declaration that Jesus was his ‘beloved son’ at his baptism and transfiguration. The ‘beloved’ element of that declaration comes from Gen 22:2 and the sacrifice of Isaac, but these declarations also allude to the Suffering Servant of Isaiah (‘well-pleased’, Isa 42:1).

The ‘firstborn’ designation is based on Ps 89:27, “Also I will appoint him my firstborn, higher than the kings of the earth”, which is an expression of Adamic dominion. This last connection is supported by Paul’s linking of the Son to ‘rulers, authorities, thrones, and lordships’ (v. 16c), which partly picks up on the psalmist’s comparison of God’s firstborn to the kings of the earth. It is also supported by the pre-eminence Paul assigns to the Son (v. 18c), which picks up on the psalmist’s ‘higher than’ comparison. So, the Son is the firstborn of all creation because he is the firstborn from the dead.[16] The context in which Christ’s sonship is set is that of the Davidic lineage (2 Sam 7:14; Ps 2:7; 89:26).

Psalm 89:27 shows that ‘firstborn’ is indicative of status and ‘all creation’ gives the scope. Revelation 1:5, “faithful witness, the firstborn of the dead, and the prince of the kings of the earth”, also quotes Ps 89:27 (‘firstborn’, ‘kings of the earth’). The two uses of the psalm show that ‘firstborn of the dead’ and ‘firstborn of all creation’ are closely related, but we should note that Colossians has ‘firstborn from the dead’. The question is whether the scope of ‘all creation’ is the old creation or the new creation or—just creation.

Paul describes God as invisible, an idea he employs in Rom 1:20, “For the invisible things of him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead; so that they are without excuse”. In terms of echoes back to the Jewish Scriptures, Heb 11:27 would suggest Exodus 33-34. Moses was not allowed to ‘see’ God because he would have died. The fact that a human being could be an image of God suggests, not that we have a high Christology in Paul, but a high Anthropology. John makes the same point in John 1:18.[17]

The Nicene and post-Nicene Fathers debated with the Arians who thought that Christ was part of creation. Colossians is relevant to this debate because it says that the Son is ‘the firstborn from the dead’ and ‘the beginning’. John picks up on Colossians when he describes Christ in Rev 3:14, “The words of the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the beginning of God’s creation.” This clarifies Col 1:18b to be about the new creation,[18] but this doesn’t mean that Col 1:15 is not more comprehensive, embracing ‘all creation’, and this is our question, and also where the Arians went astray.

John takes ‘beginning’ and ‘creation’ from Colossians and establishes that the Son is part of the new creation as its firstborn from the dead. It doesn’t matter that ‘firstborn’ is a metaphor for resurrection from the dead. Genesis clearly shows that the purpose of God in creation was to create an image (a Son; cf. Gen 5:3; Luke 3:38), and this he has done in the person of Jesus Christ. Trinitarianism and Arianism strike at the heart of this Jewish gospel because one party proposes that the Son was eternally begotten while the other party insists that the Son was created before the beginning of Genesis.

The difference between ‘firstborn of all creation’ and ‘firstborn from the dead’ is that the first looks like a title whereas the second looks like a statement of fact. Jesus is more explicit about being born from the dead when he states that he was dead but was now alive for evermore (Rev 1:18). We can therefore be certain that Christ has his position as ‘firstborn of all creation’ because he is firstborn from the dead. However, the ‘all’ of ‘all creation’ is picked up in the expression ‘all things’ which Paul then specifies in terms of various powers, and this raises the question of whether ‘all creation’ is just that, all creation.

New Creation

The question of what Paul means by ‘rulers, authorities, thrones and lordships’ is contested in scholarship. The topic usually goes under the traditional title of ‘principalities and powers’.[19] The meaning of the individual words is not contested and the range of suggestions is well-known: civil and religious authorities, demonic[20] powers, spiritual forces and angelic orders. Our objective is to answer the question why there is a reference to rulers, authorities, throne and lordships alongside the mention of the body of the church in a declaration about Christ and creation. One answer would be that the various powers are part of a new creation. If this is the case, Paul is configuring a common turn of speech for his own theological purposes.

There are four problems with this answer.

(1) It might be thought that an old and a new creation are different complete creations and that a new creation replaces any old creation. However, with Paul, the new creation happens within (and from) the old creation and Christ is the firstborn of that creation in being firstborn from the dead. The concept of the ‘new creation’ is about newly created men and women in Christ (2 Cor 5:17; Gal 6:15; Eph 2:10, 15; 3:9; 4:24; Col 3:10); it is not, ostensibly, about principalities and powers.

Paul references creation generally (Rom 1:20, 25; 8:19-22; Eph 3:9; Col 1:23), as well as the detail of Genesis (1 Cor 11:9). For example,

…if indeed you continue in the faith firmly established and steadfast, and not moved away from the hope of the gospel that you have heard, which was proclaimed (khrucqe,ntoj) in all the creation (pa,sh| th/| kti,sei) under heaven, and of which I, Paul, was made a minister. Col 1:23 (NASB)

Paul quotes Mark 16:15 here, “Go into all the world and preach (khru,xate) the gospel to all the creation (pa,sh| th/| kti,sei)”. The example shows that the scope of ‘all creation’ in Col 1:15 embraces all creation but only insofar as Paul defines its scope in terms of powers. Creative work in relation to Christ does not therefore have to be part of the new creation; it could be corresponding creative work.

Another example of the general concept of creation is Rom 8:19-22,

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of him who subjected it in hope; because the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God. We know that all the creation has been groaning in travail together until now… Rom 8:19-22 (RSV revised)

This is creation subject to Adamic condemnation and waiting in travail until ‘now’ – Paul’s day.[21]

(2) While Paul specifies the scope of ‘all things’ in terms of powers, there is the problem of saying when ‘rulers, authorities, thrones and lordships’ were created ‘in him’: [22]

For in him all things were created (evkti,sqh), both in the heavens and on the earth, the things visible and the things invisible, whether thrones or lordships or rulers or authorities. Col 1:16 (KJV revised)

The aorist passive ‘were created’ begs the question of when these powers were created ‘in him’. The answer lies in Paul’s dispensational view of what was taking place in Christ and when this creative work was determined:

He made known to us the mystery of his will, according to his kind intention which he purposed in him that in the dispensation of the fulness of times he might gather together in one all things in Christ, both which are in heaven, and which are on earth; even in him: Eph 1:9-10 (KJV revised)

According as he hath chosen us in him before the foundation of the world, that we should be holy and without blame before him in love: Eph 1:4 (KJV)

For all the promises of God in him are ‘Yes!’, and in him ‘Amen!’, unto the glory of God by us. 2 Cor 1:20 (KJV revised)

What was created in Christ in apostolic times was determined before the foundation of the world and it included the various powers of Col 1:16 as well as the gathering together of Jew and Gentile in one body. The purpose of God is centred in Christ and therefore the powers that were created for those times were also created in him. The intertextual key here is to trace what was in Christ and in him and determine when these things were decided – and the answer is – before the foundation of the world.

There is a change of tense and prepositions in the next clause,

All things have been created (e;ktistai) through him (diV auvtou/) and to him (eivj auvto.n).

The shift from the aorist to the perfect tense establishes the meaning of the aorist: that all things were created in Christ before the foundation of world in the sense that they were determined (purposed, Eph 1:9-10; promised, 2 Cor 1:20; chosen, Eph 1:4), but now they have been created through him and to him (not ‘towards’, v. 20). In the gospel age it was not only the body of Christ that was created; the various powers were also brought under Christ – they worked for him. However, this does not make their creation part of the new creation of men and women in Christ.[23]

(3) While it is straightforward to understand the creation of men and women in Christ, we might ask why the various powers should also be regarded as in him? There is, after all, no baptism into Christ for the powers. Clause v. 16c answers this question. Christ is the firstborn of all creation, not only on account of his being the first born from the dead (v. 18c), but because (o[ti, v. 16c) various powers were created in him – this is the outworking of Ps 89:27 – that the firstborn would be higher than the kings of the earth. Subordinate powers derive their power from the king and this is expressed by their having their position in him.

(4) Wright offers an objection to the above exegesis. He says,

“it reduces evn auvtw/| and diV auvtou/ to terms simply of eivj auvto.n in a way which would scarcely be comprehensible to any first century reader acquainted with the Jewish background of Paul’s thought.”[24]

It is important to distinguish the sense of diV auvtou as ‘through him’ — this is not a causal sense, as if to say it is because of him something was done, (though this may be generally true). But rather the sense is that of an intermediary through whom something is done, or an instrument through which something is achieved — the Greek is used when describing those who believe through John the Baptist (John 1:7); when Peter says God did miracles through Jesus (Acts 2:22); when Paul questions whether he gained through any he sent to Corinth (2 Cor 12:17); when Paul describes Christ as an intermediary (Eph 2:18; and other verses making similar points); and these are just typical examples of the twenty verses in the NT which use this construction.

This means that we ought to take note of the change of tense from the aorist, which is associated with ‘in him’, and is about purpose and intention, to the perfect which is associated with ‘through him’ and ‘to him’, and which reflects the reality of creating these powers. With Christ in heaven, Paul can say that all things have been created through him by God and they have been created to him.

A first century reader would certainly know the distinction between God intending to do something and this being as good as done, and then God actually doing it (Rom 4:17) – so Wright’s objection seems misjudged. But we might ask why Christ is creating powers in the first place. The answer lies in the Great Commission. Jesus stated to his disciples that “All power (evxousi,a) is given unto me in heaven and earth. Go ye, therefore, and teach all nations…” (Matt 28:18-19). If all power has been given to Christ, it follows that he would create powers in relation to the nations where the disciples will preach and with which they must interact and engage (see Section B). The commission explains Paul’s cosmology.

In view of (1) – (4), we might ask whether there is any concept of a new creation in the first strophe. Here we can say that the second kai. sentence in vv. 17-18a introduces the body of the church. Thus, the first kai sentence introduces a further thought about Christ and all things, and the second kai sentence makes a corresponding statement about the church.

And (kai.) he is above all (pro. pa,ntwn), and (kai. ) in him all things hold together. And (kai. ) he is the head of the body of the church.[25]

Christ is said to be ‘above’ all (pro. pa,ntwn) in terms of his position;[26] this statement compares with his being ‘firstborn’ (prwto,tokoj) of all creation. The repetition is indicative of a refrain in a hymn.[27] All things ‘hold together’ in him – the verb (suni,sthmi) makes more sense as ‘stand together’ in this passage (cf. Gen 40:4; Ps 39:1; Luke 9:32); the powers stand together in Christ.

The potential misdirection here is that with the mention of the body of the church, we lose sight of the fact that the passage is about the powers which Paul refers to as ‘all things’. For example, we could try and include the powers in the body, so that the body is not just the church,[28] but this misunderstands the flow of thought in the passage. The expression ‘all things’ is very common, but its scope is set by its context of use. In this passage, Paul defines his scope in terms of powers in v. 16 and then ties the passage together by recapitulating his point in v. 20.

All Things

In Genesis, God created all things in heaven and earth and the sea (Acts 14:15; 17:24; Rev 4:11; 10:6). We also see that all things were placed under Adam (Gen 1:26; Ps 8:6). He was given dominion over all the beasts of the field (not the beasts of the earth), having had them first presented as companions (Gen 2:19; Ps 8:6-7). Adam was given all things to eat (vegetable/animal, Gen 1:26, 29).

We have then the following:

All things created to fill heaven, earth and sea.

All creatures placed under a man, ordered by him.

All foodstuffs given to a man to eat.

Psalm 8 is an exposition of Genesis 1-2, and it acts as a filter for Paul’s usage of ‘all things’. He employs the expression from Psalm 8, and through this passage, the creation of Genesis 2 is brought as a backdrop into Col 1:15-20.

For thou hast made him a little lower than the angels, and hast crowned him with glory and honour. Thou madest him to have dominion over the works of thy hands; thou hast put all [things] under his feet: all sheep and oxen, yea, and the beasts of the field; the fowl of the air, and the fish of the sea, [and whatsoever] passeth through the paths of the seas. Ps 8:5-8 (KJV)

For Paul, this position of Adam was a type for Christ who was also given dominion over all things. The things include rulers and authorities, thrones and lordships, and they may be visible or invisible, in heaven or on earth. This aspect of Christ’s work, is like Adam’s lordship over the beasts of the field, as illustrated in his naming of them.

…far above all rule (avrch/j) and authority (evxousi,aj) and power and lordship, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in that which is to come… Eph 1:21 (RSV revised)

We have here the same collocation as in Col 1:16, traditionally translated ‘principalities and powers’. Christ is far above these powers, not only in the present apostolic age but in the age to come – the age of the kingdom. Commentators use the term ‘cosmic’ to describe Christ’s lordship over the powers.[29] It is important, however, to note that these powers are not just part of Paul’s present but also those that will exist in the age to come.

It is worth noting at this point that Eph 1:21 answers an objection by some that Col 1:15 cannot be an Adamic typology because Adam did no creating.[30] The answer to this is simply that the type for the powers being created through Christ is the animals being named through Adam.

The use of ‘all things’ in relation to the powers is straightforward and clearly based on the Adamic typology of dominion. What about the use of ‘all’ in relation to the body of Christ? That Christ is the firstborn from the dead ensures his position as firstborn of all creation, but the dead are his brothers and sisters who will be raised in their turn (Rom 8:29, ‘firstborn’, ‘image’ links with Col 1:15). So, there is a basis for the use of ‘all’ in relation to those ‘in Christ’ because there are many of them:

Who is the beginning, the first-born from the dead; so that[31] he himself might be preeminent among all (pa/sin).

The second strophe (beginning v. 18b, ‘who’) introduces the ‘all’ who are the body of the church. The question arises as to whether vv. 18b-20 is just about the church.

For in him he was pleased for all fulness to dwell[32]

And through him to reconcile all things (ta. pa,nta) to him, having made peace through the blood of his cross;

through him, I say, whether things on the earth or things in the heavens.

The thought here moves from the church which embodies the fulness of God to the reconciliation of all things through Christ. It might be thought that the fulness dwelt only in Christ, but this does not reflect the relationship of Christ to the body: “Which is his body, the fulness of him that fills all in all” (Eph 1:23; 3:19; cf. Col 2:9). This alludes to the dedicatory sacrifices of the tabernacle, after which the glory of the Lord filled the sanctuary (Exod 40:34).

We should also note a contingency here: God was pleased for all fulness to dwell in him – the aorist euvdo,khsen (‘pleased’) suggests a time when the fulness of God came to dwell in him. If we think only of Christ, the intertextual link is with his baptism (Luke 3:22), and this identifies the Father as the one who is pleased. If we think also of his body, then we have a statement about God’s intention that all fulness should dwell in his body (before the foundation of the world).[33]

Moving on from v. 20, Paul goes on to talk about reconciliation in relation to believers, introducing the link with the expression ‘And you…yet now has he reconciled’ (v. 21), and this can mislead readers into interpreting ‘all things’ in v. 20 as a reference to believers.[34] The mention of reconciliation in v. 20 does not embrace the church because Paul goes onto clarify that the ‘all things’ are those things on earth and in the heavens. Here, Paul reverses the order of these terms from v. 16 (as an inclusio), (‘the heavens and the earth’), and this secures the reference of ‘all things’ in v. 20 to be the powers of v. 16.[35] We know that these are Jewish and Gentile powers because of Paul’s mention of ‘peace’ (see Section B). The work of reconciling these powers is based on Christ already having made peace between Jew and Gentile through the blood of the cross (Eph 2:14-18).

This work of reconciliation was not completed in Paul’s day but, rather, God’s purpose was to reconcile the powers. Given Paul’s expectation of the imminent return of Christ to set up God’s kingdom, this work of reconciliation between the powers presently on earth and those yet to come is just his concomitant belief about what was going to happen.[36] For Paul, but not for us, it was all happening there and then.

Christological Monotheism

There isn’t an obvious monotheistic emphasis in Col 1:15-20; we only have to compare the passage with 1 Cor 8:6 to see this point. The language of ‘one and only’ is absent. The argument for the passage being an expression of christological monotheism is grounded in seeing a Wisdom Christology in the text. This is simply the observation that Paul relates Christ to creation in the same way as Wisdom in the Jewish Scriptures and Second Temple writings. This sees Wisdom as an agent in creation and an image of God. A consequence of this comparison is that Christ must be the incarnation of the Son (and pre-existed as such[37]), otherwise, he cannot have been involved in creation (the comparison would be meaningless). Hence, to say that Christ is the image of God, is to express an intimate ‘Wisdom-like’ association with God such that Paul’s monotheism can be said to ‘christological’.

At the risk of knocking down a straw man, the counter-argument to the above position is as follows: Col 1:15-20 is about a changing creation, a comparison between Christ and Adam, both the image of God. The terms of the change concern Christ’s position and status in relation to various powers. The comparison with Adam is with his dominion over creation. There is no comparison with Wisdom. Traditional Jewish monotheism is unaffected by the passage because a comparison with Adam does not affect monotheistic understanding, since he was also the image of God.

It is how scholars interpret the passage that makes it a key text for Christological Monotheism. A straightforward reading of the passage shows that God the Father is the creator behind the reality that the passage depicts (v. 12): he is the one who is pleased for all fulness to dwell in Christ and his body; he is the one who created all things in Christ; and he has now created all things through Christ and to him; and he is the one who reconciles all things: “For in him he was pleased for all fulness to dwell…and through him to reconcile (avpokatalla,ssw) all things…”. Our inference, therefore, should be that the creator and the reconciler are one person—the Father, and that there is nothing in the passage that requires us to develop a Christological Monotheism.

Wisdom Christology

Reading a ‘Wisdom Christology’ in Col 1:15-20 is common.[38] Considering Christ as a mediator or the one through whom God creates does not of itself give you a ‘Wisdom Christology’. If some Jewish writers thought of Wisdom as an ‘agent’[39] in creation, saying the same of Christ, does not show that Paul is developing a deliberate contrast with Wisdom or that he is thinking of Christ as the ‘Wisdom of God’. [40]

Some examples of points made in favour of a ‘Wisdom’ interpretation are: Dunn says that Wisdom is spoken of “as created by God (Prov. 8:22; Sir. 1.4; 24.9) and as the agency through which God created (Prov. 3:19; Wisd. 8.4-6; Philo, Det. 54)”.[41] Wright, developing the work[42] of C. F. Burney, points to the use of avrch, in Prov 8:22 (LXX), and the use of eivkw,n in Wisd 7:26. Burney himself links the notion of ‘firstborn’ in Colossians with his translation of Prov 8:22-25, ‘The Lord begat me (ynnq) as the beginning of his way’ and ‘I was brought forth (ytllwx)’.[43] We can evaluate these points as examples[44] and this will give us an indication as to whether we should pursue the ‘wisdom’ line of interpretation.

The priority that Paul gives to the Jewish Scriptures implies that were he to compare Christ to Wisdom, he would quote or allude to Proverbs 8, and scholars (e.g. Wright) have claimed that he does so in Col 1:15-20. We can use this text as a test case to decide whether there is a Wisdom Christology in Colossians 1.

The Lord acquired me (ynnq), the beginning (tyvar) of his way (wkrd), the foremost (~dq) of his works, from of old (zam). I was set up from everlasting, from the beginning (varm), from the earliest times of the earth. When there were no depths, I was brought forth (ytllwx); when there were no fountains abounding with water. Before the mountains were settled, before the hills was I born (ytllwx) … Prov 8:22-25 (NASB revised)

The translation of Prov 8:22 is contested. We justify our translation as follows:

(1) The common verb (hnq) is mostly translated (80+ times) as something like ‘acquire, get, buy, purchase’; the KJV has ‘possess’, but this is a rare choice (e.g. Gen 14:19, 22; Ps 139:13). In Proverbs, getting wisdom is a common motif (Prov 1:5; 4:5, 7; 15:32; 16:6; 17:16; 18:15; 19:8; 20:14; 23:23) and the overwhelming use of the verb. The RSV or NET ‘created me’ is based on the LXX and the versions, and the hypothesis of a second root confirmed by Ugaritic.[45] Cognate nouns and adjectives follow the majority usage of the verb in the Hebrew with appropriate variations; again, Ps 104:24 is treated differently by the RSV and NET. Possession would follow from acquisition, but ‘to create/make’ seems theologically motivated in the versions even with the hypothesis of a second root as backup.[46]

(2) The word tyvar is commonly given the range of meanings, ‘first, beginning, chief’. A parallel text,[47] Job 40:19, has ‘tyvar of the ways of God’ for Behemoth, and this is variously translated ‘chief/first’, KJV, RSV, NASB, NET). This looks like a quotation and application of Prov 8:22. Furthermore, Burney notes that tyvar is being used substantively in apposition rather than adverbially ‘in the beginning’, and that tyvar without b is not used adverbially in the Hebrew Bible, although it is theoretically possible.[48] Proverbs 4:7 uses tyvar and hnq,

Wisdom is the principal thing (tyvar); therefore, get (hnq) wisdom: and with all thy getting get understanding. Prov 4:7 (KJV)

The beginning of wisdom is: acquire wisdom; and with all your acquiring, get understanding. Prov 4:7 (NASB)

Wisdom is supreme—so acquire wisdom, and whatever you acquire, acquire understanding! Prov 4:7 (NET)

The question is whether Wisdom considered herself the beginning or chief of God’s way. Given the self-evident reflection upon Genesis 1 in the poem, and the temporal use of tyvar in Gen 1:1, the best conclusion is that Wisdom did in fact consider herself to be the beginning of God’s way.

(3) The parallel clauses, ‘the foremost of his works, from of old’, also have the same temporal sense; ~dq can be ‘before’ in time or place (Holladay) but, although most translations opt for ‘before’ here, the RSV tradition of translations opts for ‘first’. It is a common noun often found in collocations, but followed by a construct noun ‘of his works’(wyl’ä[‘p.mi), something like ‘first/foremost’ is correct. The adverb ‘from of old’ (zam) qualifies the verb ‘to acquire’, as indicated by the verb ‘to set up’ being qualified by ‘from everlasting’, ‘from the beginning’, and ‘from the earliest times of the earth’.

On this basis, (1) – (3), we have presented a translation of Prov 8:22-25 that is neutral as regards linking the text with Col 1:15-20; we haven’t sought to slant the translation to engineer a link, a charge which could be levelled at Burney. He uses vv. 23-24, ‘I was set up’ and ‘I was brought forth’ to infer ‘The Lord begat me’ for hnq, stretching the semantic domain of ‘to get’ (gat), stating “Now the idea of buying or acquiring from an outside source may clearly be excluded without argument, since Wisdom is certainly not pictured as something originally external to God.” This is fallacious reasoning as regards linguistics, but it highlights Burney’s theological motivation.[49]

If we set Colossians and Proverbs side-by-side, it doesn’t appear obvious that there is a direct quotation or allusion:

The Lord acquired me, the beginning of his way, the foremost of his works, from of old. I was set up from everlasting, from the beginning, from the earliest times of the earth. When there were no depths, I was brought forth; when there were no fountains abounding with water. Before the mountains were settled, before the hills was I born… Prov 8:22-25 (NASB revised)

Who is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation…Who is the beginning, the first-born from the dead… Col 1:15-18

The only possible link here is with ‘beginning’, but in Colossians the beginning is the new creation, whereas in Proverbs it is before the Genesis creation; this is linking with Gen 1:1 and not Prov 8:22.

However, even if there is no actual quotation or allusion of/to Prov 8:22-25,[50] Burney presents an argument (updated by Wright) based, not on the actual meaning of tyvar in Prov 8:22, but the “different possible meanings of tyvarb in Genesis 1.1, made possible by the identification of tyvar with Wisdom implied in Proverbs 8.22”.[51] This is an argument about Colossians alone and not Proverbs. The theoretical question in the philosophy of language is whether intertextual links can be established with possible as opposed to actual meaning; Wright and Burney cite no philosophical justification.

If a possible meaning of tyvar is ‘firstborn’, this doesn’t make it the meaning instantiated in Proverbs. The same point applies to the possible meaning of ‘supreme, chief, foremost’ for tyvar; we can’t claim a link with pro. pa,ntwn (‘above all’) in Col 1:17 unless this meaning is in Proverbs. Likewise, for the other possible meaning of ‘head’ for tyvar — we can’t link this to Col 1:18a.[52]

To repeat, there is an actual link with one sense of tyvar (avrch, , ‘beginning’, v. 18c; Prov 8:22 (LXX), although the beginnings are different), but this doesn’t give you a basis for saying Paul is involving several possible senses of tyvar in his Greek.[53] If Paul is involving possible senses of tyvar in his thoughts, these don’t contribute to any linkage with Proverbs 8 or Genesis 1, simply because of their absence in those texts. The upshot of this is that the argument doesn’t strengthen any claim that Paul is presenting a ‘wisdom’ Christology.

There are obvious differences between Colossians 1 and Proverbs 8 and these preclude any meaningful quotation or allusion of Proverbs 8 in Colossians 1 on the part of the Spirit through Paul.

- In Proverbs 8, Wisdom is related to the geography of the Genesis creation; in Colossians, Christ is only related to the creation of the powers. Moreover, Wisdom is not an agent in creation, but ‘with’ God. She is an agent in Prov 3:19 but, again, it is in relation to the geography of Genesis.

- There is no pre-existence to Wisdom; she exists (continually) from the beginning (Prov 8:22);[54] and she is a personification. The notion of pre-existence, as it is applied to Christ by theologians, pertains to the Son, an incarnation, and the birth of Jesus.

- Wisdom is born, but she is not said to be ‘firstborn’ (tyvar in Proverbs is based on Gen 1:1 and does not carry the ‘firstborn’ sense). The notion of ‘firstborn from the dead’ in Colossians has no connection with the ‘birth’ of Wisdom (‘I was brought forth’, v. 24), because there are no later like-born comparable to Wisdom; there is a connection with Adam, who is a firstborn of later like-born.

- Wisdom is not said to be an ‘image’ of God in Proverbs; and we cannot just draw in Wisd 7:26 (or Philo for that matter) and its use of ‘image’ for Wisdom (or the Logos) in order to secure an allusion to Wisdom in Proverbs.

- For suppose the Wisdom of Solomon does quote and allude to Proverbs 8, its use of ‘image’ does not tie into Proverbs 8 and is its own contribution.

- If Paul alludes to (or quotes) Wisd 7:26, this doesn’t then necessarily take him to Proverbs; he may very well only be using the Wisdom of Solomon.[55]

- Proverbs 8:22-31 goes back earlier than Genesis because it envisages a time ‘from the earliest times of the earth’ and ‘from everlasting’ (v. 23). This is not the correct ‘time’ for a comparison with Christ as the firstborn from the dead, the beginning of a new creation.

- The Genesis beginning is not the same beginning as Prov 8:22, and Colossians 1 alludes to the Genesis beginning (Gen 1:1, 26-28, ‘beginning’ ‘image’). The beginning in Proverbs 8 is ‘the beginning of his way’; in Genesis it is the beginning of a material creation.

- The idea of ‘firstborn of all creation’ is about position and status, and not temporal priority. The connections between Genesis and Proverbs shows that ‘the beginning (tyvar) of his way’ is a temporal notion.

- It is not clear that Wisdom can be said to be part of the material creation, even as ‘the foremost of God’s works’. On the other hand, Christ is part of a new creation as the firstborn from the dead.

The above objections, (1) – (8), are pitched generally against any attempt to relate Wisdom in Prov 8:22-31 with Col 1:15-20. However, this is not to deny that Proverbs 8 and Genesis 1 were not (mis)read together as mutually explanatory in the Second Temple period. Our argument is that the Spirit through Paul is going straight to Genesis (not Proverbs 8).

Conclusion

Wright lists three objections to a pre-existence reading of Col 1:15 – first, the present tense, ‘who is the image of the invisible God’ refers to ‘the Son’ from the point of view of Paul’s present; secondly, the concept of ‘image’ is essentially a human concept; and thirdly, God’s purpose is centred in a chosen man. These are powerful points.

Wright’s objection to these points is that they make vv. 16-17 either

“refer not to the original creation but to the new creation…Or they may refer to the original creation, but instead of claiming that Christ was active in mediating this creation at the beginning they may be suggesting simply that it was God’s intention, in creating the world, that it should find its fulfilment in him”.[56]

Wright’s ‘either-or’ is a false dilemma. As we have seen, vv. 16-17 refer to the (visible and invisible) powers of creation over which Jesus had a position of lordship (cf. 1 Cor 8:6); these verses are not about Christ mediating creation in ‘the beginning’ (Jesus is the beginning of the New Creation). Wright has been misled by a comparison with Wisdom, but such a comparison has not explained why the Spirit would quote or allude to Proverbs through the ‘interpretative development’ of such figures as Philo when Proverbs itself lacks the intertextual links to Colossians. Pre-existence is therefore imposed on the text (as well as on Wisdom), and we may suspect the influence of later church doctrine.

Section B

Introduction

W. Wink offers a broad definition of ‘principalities and powers’ – they are “the inner and outer aspects of any given manifestation of power.”[57] His definition faces two ways in order to capture making a reference to actual concrete civil and religious authorities as well as something more abstract like the ‘structures’ of power. If we follow Wink, we could be more concrete or abstract in how we read the terms as this takes our fancy.

This is straightforward enough; the exegetical question for us then is how we should handle anything in the text that apparently suggests something not on the earth, such as angels, demons, spirits and the heavenly places. Our method of approach is to pass comment on the text, but we don’t assume that NT writers are just reflecting their times;[58] we allow for the possibility that they have a distinctive view that was taught throughout the churches by the apostles.[59] This is a critical difference with other methods of approach to the texts, which seem to always hook the text to some socio-historical context or other, as if the NT church could not be doing something distinctive in their thinking across a broad range of ideas and not just their Christology.

We have noted (above) four interpretations of ‘principalities and powers’ in Col 1:16: civil and religious authorities (viewed concretely or abstractly); angelic orders; demonic powers; and spiritual/social forces at work among people. These are well-trodden paths among commentators. Our proposal is a nuance of the interpretation ‘human powers’. Colossians 1:16 is about these powers (viewed concretely or abstractly) in Paul’s present and with regard to the future kingdom. Those seen on the earth obviously pertain to Paul’s present and those ‘in the heavens’ are of the future kingdom. We therefore eschew the more common suggestion that the invisible things in the heavens refers either to demonic powers or angelic orders. Given Paul’s expectation of an imminent return of Christ to set up the kingdom, his statement that the powers on earth and in the heavens have been created in Christ is part of that expectation. Paul’s use of the language of powers in this way constitutes a criticism of Jewish cosmological fables (Tit 1:14).

On a first look, the text has some ambiguity,

For in him all things were created, both in the heavens and on the earth, the things visible and the things invisible, whether thrones or lordships or rulers or authorities. Col 1:16 (KJV revised)

This could be saying that some powers are heavenly and some earthly, for example, thrones and lordships might pertain to heaven, while rulers and authorities might relate to earthly powers. Or it could be saying that all the powers listed are both earthly and heavenly at the same time depending on your perspective. Or it could be saying that all of these powers might be either heavenly or earthly, i.e. there might be heavenly thrones and different earthly thrones, and so on.[60] Whatever we say, they ‘were created’ and this is not about assigning a new status or reconstituting existing powers but, foreseeing Christ, creating them in and around him.[61]

Thrones and Lordships

If we examine texts where the terms, ‘rulers’, ‘authorities’, ‘thrones’ and ‘lordships’ occur separately, biblical and extra-biblical, up to and including the time of the NT writers, the majority of examples will relate to power exercised by human beings. This isn’t enough to settle Paul’s meaning because ‘rulers and authorities’ is a collocation that is used elsewhere in the NT and we need to determine whether, as such, it has a specialized use in Paul.

The plural ‘thrones’ is used in respect of the kings of the earth (Luke 1:52), as well as the twelve (Luke 22:30). There are twenty-four thrones around the throne of God (Dan 7:9; Rev 4:4, 10). The most direct connection with Christ are the thrones of the twelve to which Christ appoints his disciples; these can be clearly said to have their authority ‘in him’. Paul may be referring to all or some of these kinds of throne; we need to look at other texts to decide this question.

When we look at these texts, there are one or two points which can mislead a reader, but once these are properly analyzed, there is nothing really to overturn the majority reading of ‘thrones and lordships’ as human powers.

The word ‘lordship’ is rare in the NT (4x), and it is used of a structure of government (2 Pet 2:10; Jude v. 8). Paul uses a similar four-fold expression of powers in Ephesians using ‘lordship’,

…far above all rule and authority and power and lordship, and above every name that is named, not only in this age but also in that which is to come… Eph 1:21 (RSV revised)

Christ has been placed into a position of rule over rulers, authorities and lordships in the age in which Paul lived and with regard to the age to come. The point here for us is that Col 1:16 is not just a statement about Paul’s present; it is a prophetic statement about the future.[62] Our proposal is that the pairing of ‘this age and the future age’ is matched in the pairing of ‘on the earth and in the heavens’.

Men and women are baptised into Christ, but another way to be in him is to be gathered around him. There is a time in the future when all things will be gathered together in Christ,

That in the administration of the fulness of times he might gather together in one all things (ta. pa,nta) in Christ, both which are in the heavens, and which are on earth; even in him… Eph 1:10 (KJV revised)

The description ‘things which are in the heavens’ is a way of talking about things then created for the future which will come from heaven and be instantiated on earth, for example, the New Jerusalem will come ‘from above’ (Gal 4:26). This means that we should read Col 1:16 as (partly) a prophetic statement[63] of what has been established in, for and through Christ for the future kingdom on earth – the administration of ‘the fulness of times’.

Paul makes a statement about ‘the things visible and the things invisible’; the invisible things concern things to come rather than angelic orders[64] or demonic powers.[65] Thrones and lordships have been created in Christ for the future because they will be gathered to him at that time. The language of the visible and the invisible is used for the present and the future and indicative of prophetic statements being made about ‘things unseen’:

For this slight momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison, because we look not to the things that are seen but to the things that are unseen; for the things that are seen are transient, but the things that are unseen are eternal. 2 Cor 4:17-18 (RSV)

The example of the unseen things that Paul gives is the resurrection body which was ‘in the heavens’ (2 Cor 5:1). This is what he was looking for – something ‘from heaven’ (2 Cor 5:2).[66]

The principle here is expressed by Paul in Romans,

(As it is written, I have made thee a father of many nations,) before him whom he believed, even God, who quickeneth the dead, and calleth those things which be not as though they were. Rom 4:17 (KJV)

Hence, there is a common connection between the language of seeing and prophecy. Faith is a conviction about things not seen (Heb 11:1) and illustrated in the example of Noah who was warned by God concerning things he as yet could not see (Heb 11:7). The prophets wanted to see the things concerning Christ (Matt 13:17) but only sometimes did they see his day (John 8:56).

We conclude therefore that the future thrones[67] created in Christ are most directly the twelve thrones that pertain to Israel, while the future lordships created in Christ pertain to the Gentiles. This suggestion is supported by the fact that the things in the heavens are ‘reconciled’ through Christ (v. 20) and reconciliation of Jew and Gentile in Christ is achieved through the cross.

Rulers and Authorities

The traditional topic of ‘principalities and powers’ now goes under the rubric of ‘rulers and authorities’. The collocation occurs as many as ten times in the NT writings, depending on how strict you are in defining the collocation (plural and singular). In order to identify these powers, we can start in Ephesians.

Unto me, who am less than the least of all saints, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ; and to make all men see what is the fellowship of the mystery, which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God, who created (kti,santi) all things to the intent that now the manifold wisdom of God might be made known by the church to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places, according to the eternal purpose which he purposed in Christ Jesus our Lord… Eph 3:8-11 (KJV revised)

This clearly places the rulers and authorities ‘in the heavenly places’ (evn toi/j evpourani,oij[68]) and gives a role to the church in making the wisdom of God known to them. They are unlikely to be demonic powers or angelic orders (working from heaven or the desert) in a passage concerned with preaching to the Gentiles.[69] The problem that commentators have with this passage is with the meaning of ‘the heavenly places’.

These places are referred to by Christ when he says, “In my Father’s house are many abiding places…I go to prepare a place for you, and if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and receive you unto myself” (John 14:2-3). These places (monh, ) are where the Father and the Son ‘dwell’ with believers in their lives on earth, “we will come unto him, and make our abode with him” (John 14:23). Insofar as believers on earth dwell in such places (in a temple, the body of Christ), they dwell with the Father and the Son. Thus, when rulers and authorities engage believers, they do so in the heavenly places.[70]

It might be thought that any rulers and authorities in the heavenly places must be literally in heaven and therefore angelic or demonic. Some commentators connect these powers to the organisation of the angels in the heavens.[71] However, in respect of the new creation, the heavenly places are open to those in Christ,

And hath raised us up together, and made us sit together in heavenly places in Christ Jesus… Eph 2:6 (KJV) cf. Eph 1:3, 20

We may think of a Christian’s place with Christ in the heavenly places in an ideal sense; Christians are on earth, but they are also dwell with Christ in the heavenly places because Christ comes and dwells with them – they are part of his body, a temple. This opens up the interpretation that rulers and authorities come to the heavenly places when they engage believers – oppose them. The dichotomy that rulers and authorities are either of heaven (demons, Satan, angels) or of the earth (human government) is therefore false. What we have here in Paul is a concept of the church as the body of Christ, a temple, in which the Father and the Son dwell with believers and from which believers witness to Jew and Gentiles and ‘in’ which rulers and authorities engage believers. This interpretation explains Paul’s comment,

…to the intent that now the manifold wisdom of God might be made known by the church to the rulers and authorities in the heavenly places … Eph 3:10 (KJV)

It is possible to confuse ‘the heavenly places’ and ‘in the heavens’; Paul does not say that God has created all things in the heavenly places but ‘on the earth and in the heavens’. The difference is that this creative work is of the visible and invisible and it is the visible authorities on earth that may come to the heavenly places. Moreover, it is worth noting that the mystery of the reconciliation of Jew and Gentile was hidden from rulers and authorities in previous ages. It was the generation of Paul who were created by God to receive the revelation of that mystery, the return of Christ, and the establishment of the kingdom.[72]

This interpretation is obviously consistent with the use of the collocation in the plural in Luke 12:11 (“bring you before the rulers and authorities”) and Titus 3:1 (“be subject to rulers and authorities”). It is also consistent with Luke 20:20 where we have the singular, “they might deliver him unto the rule and authority of the governor”, but this might not be the same collocation.[73] This leaves the other occurrences of the collocation in Ephesians, Colossians and 1 Corinthians to investigate.

A counter-argument to the above interpretation is based on Eph 6:12,

Put on the whole armour of God, that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil. For it is not a wrestle against blood and flesh, but against rulers, against authorities, against the world-rulers of this darkness, against the spiritual things of wickedness in the heavenly places. Eph 6:11-12 (KJV revised)

Here it is argued that principalities and powers cannot be human authorities because Paul says ‘it is not a wrestle against blood and flesh’. Following this line of interpretation, one view is that Paul is not talking about human opponents; he is talking about the devil and demonic powers;[74] another view is that Paul is talking about angelic orders.[75] This last view is supported by the allusion in ‘wrestle’ (pa,lh, Arndt & Gingrich), which is to Jacob’s wrestling with the angel (Gen 32:24, LXX, palai,w). The contrast offered is pitched at the level of a non-human person, whether the devil, demon or an angel, and the various powers are then seen as diabolic or angelic.[76]

In English, ‘flesh and blood’ is a well-known idiom.[77] In the Greek New Testament, the same idiom might embrace human nature (1 Cor 15:50) or refer to human beings (Matt 16:17; Gal 1:16). As an idiom for human beings, it carries a particular reference to the thinking of the flesh, and it stands in contrast to divine revelation. Jesus says, ‘Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, Simon’ (Matt 16:17) and Paul says, ‘To reveal his son in me…I conferred not with flesh and blood’. The Greek of Eph 6:12, along with that of Heb 2:14, is ‘blood and flesh’, and if it is an idiom, it is about the physical makeup of the human being; Heb 2:14 is clear in this regard.[78] The wrestling that Christians do not do is physical; instead, their ‘standing against’ is a metaphorical wrestle against various powers where the wiles of the devil are being encountered.

The contrast that Paul makes in ‘not a wrestle against blood and flesh’ is not one between human and non-human opponents, but one between the physical and the mental – the ‘wiles’ of the devil.[79] That Paul is talking about thinking is further shown by his metaphor of ‘darkness’ and his reference to ‘spiritual things of wickedness’ (see below).

The key to Eph 6:12 is the mention of ‘the wiles of the devil’ because Paul repeats the preposition ‘against’ (pro.j) from ‘against the wiles of the devil’ in ‘against rulers, against authorities, against the world-rulers of this darkness, against the spiritual things of wickedness in the heavenly places’. Furthermore, the clause that opens v. 12 begins with o[ti and this shows that it is explanatory for ‘the wiles of the devil’. Paul is saying that ‘the wiles of devil’ can be seen in the behaviour of various powers and the spiritual things of wickedness.[80]

Ephesians 6:11-12 is about the wiles of various powers that the first century church encountered in their preaching; it is not literally about a devil or demons, nor about angels. The ‘wiles’ (h` meqodei,a) of the devil uses a word that occurs once elsewhere in Eph 4:14,

…so that we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness in deceitful wiles. Eph 4:14 (RSV)

This puts the thinking of men and particularly their religious doctrine to the foreground, and it allows the suggestion that ‘the devil’ of Eph 6:11 is a personification of the various kinds of opposition that Paul is encountering and which confront the ecclesias.[81] Paul was saying that their fight was not a physical struggle but a spiritual one against various powers and their ideas.[82]

This is the best sense for ‘spiritual things of wickedness in heavenly places’. The term ‘spiritual things’ (ta. pneumatika.[83]) is used by Paul elsewhere for the spiritual things of the Spirit (1 Cor 2:13; 9:11; 14:1). Those in the heavenly places were those Jews who had infiltrated the church and who manifested the spiritual things of wickedness in their opposition to the gospel.[84]

Ephesians 6:12 has ‘world-rulers of this darkness’.[85] The word for ‘world-rulers’ (tou.j kosmokra,toraj) is used variously in Greek texts of spirit beings or gods who control parts of the cosmos, human rulers or kings; in the singular, it is used of Satan and even the Angel of Death (Arndt & Gingrich). This data, coupled with a reading of ‘non-human’ for ‘not against blood and flesh’, leads commentators to posit demonic rulers as its reference in Eph 6:12.

Given this general Greek usage, what use is Paul making when he relates ‘world-rulers’ to ‘this darkness’? He would seem to have something specific in mind because he uses the demonstrative ‘this’ for the darkness. What does Paul mean by ‘this darkness’? Paul’s commission to the Gentiles was to deliver them from darkness to light (Acts 26:17-18; cf. 1 Pet 2:9-10), and in his letters, there is an emphasis on the darkness of the Gentiles (e.g. Rom 2:19; 2 Cor 6:14). In Ephesians, he is addressing Gentiles (Eph 2:11; 3:1, 6, 8; 4:17) and the darkness is Gentile thinking (Eph 5:8, 11). The world-rulers of the time were the Romans, and this is the most natural reading of Paul’s phrase – they were ‘the world-rulers of this darkness’. If we break-up the compound word ‘world-ruler’, we find Paul using ‘world’ of the Gentiles in Ephesians (Eph 2:2, 11-12).

There is a thematic connection between Eph 6:12 and Col 1:13, “Who hath delivered us from the power of darkness, and hath translated us into the kingdom of his dear Son” (Col 1:13). This is a quotation of Luke 22:53 which records Jesus referring to the hour of the ‘power of darkness’ from which he was not delivered. Jesus, however, had delivered Paul and his Gentile converts from the power of darkness. Their transfer to the kingdom of God shows that the power of darkness was itself a kingdom with rulers (the echo is to Abner who translated/delivered the kingdom of Saul to David, 2 Sam 3:10). Our conclusion therefore is that ‘this darkness’ is the ‘power of darkness’ embodied in the rule of Rome.

Ephesians 6:12 is a catalogue of various kinds of opposition to the gospel: it refers, in order, to rulers and authorities, in which it agrees with Eph 3:8-11 (see above); it lists the world-rulers of the day (Rome); and it mentions those Jews who were engaged in a counter-reformation inside the church.

The next ‘rulers and authorities’ text to consider is Col 2:14-17,

Blotting out the handwriting of ordinances that was against us, which was contrary to us, and took it out of the way, nailing it to his cross.

Having put off from himself rulers and authorities, he made a shew of them openly, triumphing over them in it.

Let no man therefore judge you in meat, or in drink, or in respect of a holy day, or of the new moon, or of the Sabbath days, which are a shadow of things to come; but the body is of Christ. (Col 2:14-17 (KJV revised)

The list of judgments are typical concerns of Judaizing Christians and Jews – meats, drinks, holy days and the Sabbath.[86] The association of these concerns with ‘rulers and authorities’ goes to confirm the reading of Jewish rulers and authorities. The context here is clearly Jewish and the most natural reading of ‘rulers and authorities’ is as a reference to those who took part in the crucifixion of Christ – the relevant tenses are in the past (aorist, perfect).

It might be thought[87] that there is a tension or contradiction between Col 1:20 and 2:15, especially in some translations (e.g. ‘spoiled principalities and powers’ KJV; ‘disarmed the rulers and authorities’ NASB). Colossians 1:20 is about reconciliation of the powers through the cross and Col 2:15 is about disarming or spoiling them. The translation issue here is whether to treat the grammatical middle (avpekdusa,menoj) as an active sense (‘disarm/spoil’) or to retain the middle sense (‘put off/divest’).

The context supports the middle sense.[88] There is a clothing metaphor here in that Paul says Christ ‘divested himself’ of rulers and authorities (cf. Col 2:9 – ‘you have put off the old man’, avpekdu,omai). The related noun (avpe,kdusij) occurs in Col 2:11, “putting off the body of flesh”. The cross might have seemed a defeat for the nascent Christian movement, but for Paul it was a triumph over the very powers that sought to extinguish the gospel. What was nailed to the cross were the ordinances of the Law, which the Jewish rulers and authorities used against the church (‘against us’) in the sense that they promoted the Law’s necessity and sufficiency.

What we have in Col 2:14-15 are two sentences describing the crucifixion with the actions of the judge and executioners transferred to Christ to show that he voluntarily submitted to the cross. The echo in nailing handwriting to the cross is to Pilate’s handwriting of the title of Christ in his judgement hall which was then put (nailed) on the cross (noted in the parenthesis of John 19:19-22). This title was in effect the legal charge against Christ (Luke 23:2). The echo in ‘openly (parrhsi,a|) triumphing’ is to the characteristic of Christ’s ministry: “I spoke openly (parrhsi,a|) to the world” (John 18:12), but the sense of ‘triumph’ is that of a triumphant procession (qriambeu,w, Arndt & Gingrich), and this is an allusion to Christ carrying his cross openly to Golgotha (John 19:17).[89]

This latter reading would be consistent with Gal 3:13, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law, having become a curse for us — for it is written, ‘Cursed be everyone who hangs on a tree’” (RSV). The curse of the Law was upon the people – the handwriting of ordinances was against them. But Christ took away the power of the Law from the Jewish rulers and authorities

Angelic Orders

The two alternative interpretations to the one proposed here for ‘rulers and authorities’ are angelic orders and demonic powers. We have not argued against these interpretations in regard to our texts. It is too large a subject for this paper to argue that Paul does not have in mind Satan and demonic powers when he uses the expression ‘rulers and authorities’.[90] We can, however, make a few points against the reading that Paul is thinking of angelic orders.

- Romans 8:38-39, “For I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” distinguishes angels from principalities (avrcai.).

- Similarly, 1 Pet 3:22, “Who is gone into heaven, and is on the right hand of God; angels and authorities (evxousiw/n) and powers being made subject unto him.” makes the same distinction between angels and authorities.

- When Col 2:14 says that Christ divested himself of rulers and authorities, this is unlikely to be a reference to angels, but to those who misused the Law, because the angels strengthened Christ during Gethsemane and were on hand (Matt 26:53; Luke 22:43).[91]

- Angels were interested in the prophesying in the church and the prophecies relating to the coming glory (1 Pet 1:12). This, however, is very different from what Paul states in Ephesians, that the fellowship of the mystery was hid in God with the intention that it be made manifest to rulers and authorities by the church (Eph 3:9-11). It is unlikely that such an intention related to the knowledge of the angels, but rather it relates mainly to God’s people (the usual recipients of revelation) and their relationship to the Gentiles in the gospel.

- Angelic orders do not feature in the Jewish Scriptures; the terminology for such orders is based in Second Temple writings and later Rabbinical writings. If ‘rulers and authorities’ is not angelic, but Jewish, this does not mean that other ‘power’ terminology is not angelic.

On the basis of (1) – (5), we reject the angelic interpretation of ‘principalities and powers’. The point here is that these terms are generally applied to cosmic and earthly powers in Second Temple writing. Our task has been to determine Paul’s application.

Conclusion

The idea of ‘rulers, authorities, thrones, and lordships’ is a kingdom orientated idea. Since Paul has already mentioned the kingdom (Col 1:13; cf. 2 Sam 3:10 KJV), this idea is not out of place. A kingdom has a king, but it also has subordinate individuals and institutions that govern on behalf of the king (e.g. the thrones of the twelve tribes, Matt 19:28). A king creates these for his kingdom and in particular he creates them when his kingdom extends over subject peoples. This was true of David and Solomon and the former kingdom of God, and it is unlikely not to be true of the kingdom of Christ. However, the kingdom of God was not yet on earth, for Christ had not yet returned. Those ‘rulers, authorities, thrones, and lordships’ of the kingdom were not yet seen.

We might ask why Christ has ‘rulers, authorities, thrones, and lordships’ in Paul’s day, but this is just a consequence of “all authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Matt 28:18) and “the Most-High rules in the kingdom of men” (Dan 4:32). All rule and dominion had been given to the Son, all power and authority, the power to create and the power to destroy, and the final judgement. In all these situations the Lord Jesus Christ had the role and position of king.

Ephesians 1 talks of all things already put under the feet of Christ, and Colossians 1 talks of all things having been created in Christ, but 1 Corinthians 15 makes it clear that all things are not subdued unto Christ until the last enemy is destroyed (1 Cor 15:24-28). As with Colossians 1 and Ephesians 1, 1 Corinthians 15 has the same ideas: resurrection, principalities, powers, and might:

…Christ the firstfruits; afterward they that are Christ’s at his coming. Then cometh the end…when he shall have put down all rule (pa/san avrch.n) and all authority (pa/san evxousi,an) and all might… 1 Cor 15:23-24

Christ was (is) the firstborn of all creation, but here the figure is that of the firstfruits of a harvest. Paul is thinking of the last days when the kingdom is delivered up to the Father. The collocation ‘rulers and authorities’ is not used, but the same words with ‘all’. There is little doubt that this makes the scope universal: all the human rulers and authorities and all the might that stands arraigned against Christ will be put down and then Christ will hand over the kingdom to the Father.

[1] N. T. Wright, The Climax of the Covenant (London: T&T Clark, 1991), 99. For an introduction to the passage as a whole, see L. W. Hurtado, “Pre-existence” in Dictionary of Paul and his Letters (eds. G. F. Hawthorne & R. P. Martin; Leicester: Intervarsity Press, 1993), 743-746 (745-746). For a reading closer to ours, see J. D. G. Dunn, Christology in the Making (London: SCM Press, 1980), 187-194.

[2] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 117.

[3] This is an important methodological choice: we are not going to argue that you can’t impose a Wisdom/Logos Christology using Second Temple texts; (see Dunn, Wright); we won’t be addressing the older proposal of a Gnostic background (see Wright for criticism); and neither will we set the passage within a cosmological scheme built from Second Temple writings which involves angelic orders or demonic powers. For a review of scholarship in the 1980s see L. R. Helyer, “Recent Research on Col 1:15-20” GTJ 12/1 (1990): 51-67.

[4] Dunn, Christology in the Making, 188.

[5] R. P. Martin, “An Early Christian Hymn – Col 1:15-20” EQ 36 (1964): 195-205 [Online]. This is the best starting point for looking at the structure of the hymn.

[6] E. McCown, “The Hymnic Structure of Colossians 1:15-20” EQ 53/3 (1979): 156-162 [Online], offers useful additional analysis to Martin; see also P. Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn Celebrating the Lordship of Christ” in Pauline Studies (eds. D. A. Hagner and M. J. Harris; Carlisle: Paternoster, 1980), 169-183 (170).

[7] We will assume that it is a hymn for the sake of structuring the essay along common lines of study. For a discussion of the question of style and whether we have a hymn and where it begins, see doubts expressed in J. F. Balchin, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn? Arguments from Style” Vox Evangelica 15 (1985): 65-94. [Online].

[8] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 104; Wright’s judgments on the history of scholarship on the question of structure are judiciously sound (106).

[9] Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Hymn celebrating the Lordship of Christ”, 176, states, “Christ is not only the ‘first-born of all creation’, he is also the ‘first-born from the dead’”. This gets things the wrong way round. The Son is firstborn of all creation because he is firstborn from the dead. In being raised from the dead, he was raised to be the firstborn of all creation.

[10] We should note that the grammar is such that the sentence that includes vv. 15-20 begins in v. 12 and hence we cannot treat the ‘hymn’ in isolation. Hence, scholars have debated where the ‘hymn’ begins.

[11] H. A. Whittaker, 7 Short Epistles (Cannock: Biblia), 10. Contra Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 109, “To a Jew of the first century, of course, a reference to the Exodus would not be of antiquarian interest. It would speak of the redemption still to be accomplished, the greater ‘return from exile’ in which Israel would finally be redeemed from her bondage.” Wright runs together the exodus and the exile, but whether Paul did so is not shown in Colossians. The exile was not about bondage, and Paul’s echoes of the exodus shows that he is not using an exilic model to understand his times.

[12] McCown, “The Hymnic Structure of Colossians 1:15-20”, 9, “This specific idea of ‘image’ has no parallel in Wisdom tradition.” He presumably means ‘image of God’, not that the concept of ‘image’ is not used for Wisdom (Wisd 7:26).

[13] Genesis is not about the beginning of the universe, not even in Gen 1:1. Dunn blunders badly here because he says an allusion to Adam here is “probably ruled out” and he goes onto correlate the passage to Jewish thinking about Wisdom; Christology in the Making, 188. We examine Wisdom Christology below.

[14] This means that the Arian controversy about Christ – whether he was a creature – is not addressed by Col 1:15.

[15] Contra C. A. Beetham, Echoes of Scripture in The Letter of Paul to the Colossians (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2008), 133, who wants temporal priority and position and status to be carried by ‘firstborn of all creation’.

[16] Contra T. J. Barling, Letter to the Colossians (Birmingham: CMPA, 1972), 78-81, who relates ‘firstborn’ to the virgin birth; and contra Whittaker, 7 Short Epistles, 10, who relates the title to the new creation; but with Dunn, Christology in the Making, 189-190, “the first strophe most obviously follows as a corollary from that of the second (rather than the reverse)”.

[17] As we have noted, commentators often make a comparison with Hellenistic Judaism and their theology of the ‘Wisdom of God’, for example, J. D. G. Dunn, The Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon (NIGTC; Carlisle: Paternoster Press, 1996), 88, and his Christology in the Making; also R. E. DeMaris, The Colossian Controversy: Wisdom in Dispute at Colossians (JSNTSS 96; Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1994). The problem with the comparison is that it misdirects the reader from seeing Adam as the type of Christ being the ‘image of God’ (1 Cor 11:7; Col 3:10). After all, Wisdom in Hellenistic Judaism is personified as a female.

[18] Thus, we have a partitive genitive because ‘firstborn from among (evk) the dead’ is partitive. It is noteworthy that ‘first born of all creation’ does not use evk, and so should be treated as an objective genitive in keeping with our discussion above; see N. Turner, Grammatical Insights into the New Testament (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1965), 122-124, for background but a contrary view; and Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn Celebrating the Lordship of Christ”, 171, for a supporting view.

[19] See D. G. Reid, “Principalities and Powers” in Dictionary of Paul and his Letters (eds. G. F. Hawthorne & R. P. Martin; Leicester: Intervarsity Press, 1993), 746-752, for an introduction to the various views and bibliography. W. Wink, Naming the Powers (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1984), chap. 2, presents the textual data more fully and he presents something of an opposite view to W. Carr, Angels and Principalities: The Background, Meaning and Development of the Pauline Phrase HAI ARCHAI KAI HAI EXOUSIAI (SNTSMS 42; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), on which see his personal preface to the book. These two books are a modern starting point, and Wink gives a bibliography of major studies up to the 1980s (p. 6). More broadly, C. E. Arnold, The Colossian Syncretism: The Interface between Christianity and Folk Belief at Colossae (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1996), should be consulted.

[20] Reid, “Principalities and Powers”, 747, notes that the powers do not inhabit idols or humans or live under the earth, unlike demons.

[21] Contra Whittaker, 7 Short Epistles, 10, who lists Paul’s new creation texts but does not discuss his general creation texts and classifies Rom 8:19-22 as a new creation text.

[22] Some translations opt for ‘by him’, but we are maintaining the parallelism with clause (B’) which has ‘in him’. The KJV uses ‘by’ for evn auvtw, which is wrong for Colossians 1. This Greek expression occurs some 88 times in the NT and it is overwhelmingly translated as ‘in him’.

[23] Contra Turner, Grammatical Insights into the New Testament, 125-126; and with Dunn, Christology in the Making, 190, who talks of God’s “intention” in Christ. Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn Celebrating the Lordship of Christ”, 173, states that ‘to him’ means that Christ is the objective of creation, but he is not taking sufficient account of the fact that Paul is concerned just with powers.

[24] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 114.

[25] Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn Celebrating the Lordship of Christ”, 179-182, shows that ‘of the body’ is essential to the passage and not a later addition.

[26] The Greek expression (pro. pa,ntwn) is commonly used for precedence (Josephus, Ant. 1:20; 3:302; 8:24; 12:90; 17:6; 20:127; War. 1:490, 498; Test. Sol. A 4:6; Didache 10:4. Temporal priority usage for the expression is less common, but an interesting example is Philo, De Cherubim 1:28. Contra Whittaker, 7 Short Epistles, 13, who says “the preposition before (pro) has a temporal force”; he fails to look at the idiomatic use of pro. pa,ntwn in contemporary Greek; Beetham, Echoes of Scripture in the Letters of Paul, 134, makes the same mistake.

[27] McCown makes the common proposal that this addition is a refrain in the hymn, breaking the two strophes; “The Hymnic Structure of Col 1:15-20”, 161.

[28] This would be a ‘world-body’ interpretation, on which see C. E. Arnold, “Jesus Christ: ‘Head’ of the Church (Colossians and Ephesians)” in Jesus of Nazareth Lord and Christ: Essays on the Historical Jesus and New Testament Christology (eds. Joel. B. Green and Max Turner; Carlisle: Paternoster, 1994), 346-366.

[29] L. L. Helyer, “Cosmic Christology and Col 1:15-20” JETS 37/2 (1994): 235-246 [Online]. Helyer wants to affirm the cosmic dimension of Paul’s talk of powers against those scholars who would reduce such terms to aspects of the new creation of men and women in Christ. We agree, but his paper is also fighting those scholars, such as Dunn, who re-interpret indications in the text that he thinks show the pre-existence of Christ; here, we disagree.

[30] As in Dunn, Christology in the Making, 188; discussed by McCown, The Regal Status of Christ, 9. McCown notes some interesting echoes reinforcing the Adamic typology of Col 1:15, including ‘fruitful and multiply’=’the gospel bearing fruit and growing, Col 1:6; and the Colossians should bear fruit, (Col 1:10).

[31] This is difficult for Trinitarians who want the Son to have been pre-eminent from all eternity – see Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 116-117, for how he handles this point.

[32] This is quoting Ps 68:16 – Beasley-Murray, “Colossians 1:15-20: An Early Christian Hymn Celebrating the Lordship of Christ”, 177.