Introduction

N. T. Wright introduces a thesis in his The Climax of the Covenant that,

“what he [Paul] says about Jesus and about the Law reflects his belief that the covenant purposes of Israel’s God had reached their climatic moment in the events of Jesus’ death and resurrection.”[1]

If he means the Law, this looks right, since Christ came to fulfil the Law. He cannot mean the Abrahamic or Davidic promises. There have been two thousand years since Christ and these promises do not look fulfilled. Rather than a climax in respect of these promises, the death and resurrection of Christ look like a watershed.

Wright expands upon his thesis by saying that Paul is engaged upon the “redefinition” of the Jewish doctrines of God and Israel (monotheism and election) by means of Christology and Pneumatology.[2] This is a significant thesis and, on initial thoughts, it looks plausible for the doctrine of election if Wright means Second Temple Judaism, but wrong if he means just the Jewish Scriptures of Paul’s day; it seems wrong for both Second Temple Judaism and the Jewish Scriptures in respect of monotheism.

We might well ask: what would need redefinition in the Jewish Scriptures if they are inspired? Of course, Wright needs to redefine monotheism and election because he has Christ and later church doctrine to ‘fit’ into a Jewish framework. Hence, Wright talks of a ‘christological redefinition’ of Jewish monotheism and sees 1 Cor 8:6 as a key text redefining the Shema.[3] The inclusion of Christ in this new Shema, Wright claims, sets a boundary and marks out Christians from Jews, making race “irrelevant to membership in the people of God”.[4] Nevertheless, Wright doesn’t affirm the replacement of Israel by the church nor the separate coexistence of Israel and the church in the purpose of God.[5] His view is a third way. Still, we might well ask whether race was ever an excluding principle for membership of the people of God, given the mixed multitude that came out of Egypt, and this is the overriding point.

Typology

Scholars are wont to consider Adam-Christology, Wisdom-Christology, Gnostic Redeemer Myths, Roman Imperial Christology, and the like, in Paul, and see differences, even conflicts, and all in their endeavour to understand Christ. They also give as much space to relating Paul to his Jewish-Hellenistic background as to his intertextual exegesis and development of the Jewish Scriptures. Our interest is in the latter because Paul is writing Scripture with Scripture as a Christian prophet; any connections with his Jewish background or with Greco-Roman culture in general is secondary and for another paper.

Wright’s thesis about Israel is that she is ‘God’s true humanity’ and his argument is typological: the Abrahamic promises are configured in Adamic terms: be fruitful and multiply, have dominion, and possess the land.[6] They are so configured, but he doesn’t indicate what he means by ‘true’ and doesn’t compare Heb 9:24, for example, with its typological notion of ‘true’ to indicate the antitype (‘figures of the true’). Certainly, Israel can be thought of as an Adamic type, but scripturally, they are not the ‘true’; in relation to Adam, the ‘true’ is Christ. The same point applies if we consider an individual as an Adamic type, such as the Arm of the Lord in Isa 45:12,[7] or if we consider a remnant (‘saints’, Daniel 7), or a king and his people (Isaiah 55, ‘thorn’, ‘brier’).[8] Wright will want to say that Christ and his people are ‘the true’, but his notion of ‘true humanity’ in respect of Israel is misleading, especially if you are working with typology where ‘type’ and ‘antitype’ are well understood categories.[9]

Whether typology is seen in a text is obviously dependent on the reader; readers are different, some will be right and some will be wrong with the typology they discern. So, for example, Wright thinks that there is an Adamic typology in Prov 8:22-31 with Wisdom being “set over the created order”.[10] This seems wrong on several levels: there are no Adamic textual links; Wisdom is female and she is ‘with’ God; and she is then ‘with’ the ‘sons of Adam’. This isn’t actually a ‘setting’ of Wisdom ‘over’ the created order.

Mistakes can also be made in analysis with the antitype. Wright characterizes Paul’s understanding as, “the role traditionally assigned to Israel had devolved on to Jesus Christ. Paul now regarded him, not Israel, as God’s true humanity”.[11] The issue that this ‘summary’ raises is the ongoing role of Israel in the purpose of God and the relationship of Jesus to Israel. That Israel has an ongoing role is proven by their return to the land in modern times (correspondingly, there is no such proof that ‘the church’ has an ongoing role). The point here is that when Paul compares Adam and Christ, Christ is presented as the antitype and not the replacement of Israel as an Adamic type. If Jesus is part of Israel, then there is no possibility of roles being devolved; the role Jesus plays will be the role Israel plays by dint of the fact he is part of Israel.

The subtle error in Wright is seen again when he says in relation to Rom 5:12-21 that “the privileges of Israel, particularly those of the fulfilment of the law and of being the children of God, have been transferred to Christ and thence to those who are ‘in Christ.’”[12] On the contrary, the promises were always centred in Christ; they haven’t been transferred to him as if they were centred in Israel; Jesus is part of Israel. Those who are unfaithful in Israel have the same position in every generation – they are of the flesh and not of the Spirit. The fact that the faithful in Israel recognized Jesus and followed him does not effect a transfer of anything; scholars are misled by the equal inclusion of the Gentiles “in Christ” into thinking there is a new body of people apart from Israel.

The key point here is to recognise that ‘Christ’ was preached in the past to the fathers and through the prophets. Faith in Christ might not have had the detail and the name, but it was possible from the beginning. It is therefore a strategic mistake to think that “The work of Christ does not merely inaugurate a new race of humanity, as though by starting again from scratch.”[13] There is no ‘merely’ here: Christ has been the foundation for the faithful since the beginning. Hence, Israel were not entrusted with the redemption of humanity,[14] as if this task did not involve reference to Christ. The Law was a schoolmaster to bring people to Christ (Gal 3:24), and so it was never the case that the Law was a different principle of redemption given to Israel, a principle which has now been replaced.

Resurrection

How we think of the resurrection and ascension of Jesus is important for our understanding of the relationship of Jesus to Israel. Furthermore, it is important for discerning and applying types that we understand the historical background underlying the scriptural material from which we are drawing the type. For example, Psalm 110 has its historical background during the rebellion of Adonijah; Solomon is anointed by the brook (v. 7), but there are enemies inside the royal court, the army, and the people, and so Solomon is told by Yahweh to ‘sit by his right hand’ until he makes his enemies his footstool.[15] The typology here is that there will be a period between Jesus’ anointment as king and his taking the throne in Jerusalem, but it is clear that the subjugation of Solomon’s enemies continues after he has gained the throne (Ps 110:5-6). Since Jesus has not taken the Davidic throne in Jerusalem, he sits at ‘the right hand of God’ now, which is a metaphor in the Psalm for the divinely supported rule of the king away from the throne.

There are several quotations of (and allusions to) Psalm 110 by NT writers.[16] The quotation of Ps 110 in Heb 2:5-11 (“putting everything in subjection under his feet”) states that not all things are yet in subjection to him. There is a time in the future when all things will be in subjection to Christ. This future time is the subject of the quotation in 1 Cor 15:25,

For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. 1 Cor 15:25 (RSV)

This picks up on ‘until’, ‘put/make’ (tyv) and ‘enemies’ from Ps 110:1, but there has been a coming prior to this subjugation (v. 23); this is therefore an application of the Psalm after the Second Advent. The phrase ‘under his feet’ is coming from Ps 8:6, although it is probable that ‘footstool’ is a figurative imagining of the earlier Psalm’s ‘under his feet’. Psalm 8 is highly Adamic and this shows that there is a parallel to be struck between the dominion of Adam and the dominion of the Davidic king.

Psalm 110 begins at the brook where Solomon is anointed, but from v. 2 onwards it is a picture of the rule of the king from Jerusalem. For the Psalm to apply to Jesus, he has to rule from Jerusalem, and ‘the day of thy power’ (v. 3) and ‘the day of his wrath’ (v. 5) resonate with normal expressions for future action like ‘in that day’. Obviously, if Christ be not raised, none of this typological application of Psalms 8 and 110 can apply.

Resurrection can be a metaphor (as in Ezekiel 37) but the resurrection of Christ and those ‘in Christ’ (1 Cor 15:22-23) is or will be literal. Wright avers that “Israel’s longed-for ‘resurrection’ had bifurcated, and was now to be seen as a two-stage process in which Jesus would rise first, solo, while his people were to follow later”.[17] This confuses the metaphorical use of ‘resurrection’ in Ezekiel 37 with the literal resurrection of the dead. Israel’s national resurrection will take place as they respond to Jesus after his return, but this is a metaphor. The general resurrection of the dead is apart from the revival of Israel, and it is this resurrection of which Jesus is the firstborn.

Jesus is Israel’s messiah-deliverer, the one who will restore the kingdom of God as it was under David, but the kingdom will conclude in a clear subordination[18] of ‘the Son’ to God: “And when all things shall be subdued unto him, then shall the Son also himself be subject unto him that put all things under him, that God may be all in all.” (1 Cor 15:28). What is interesting here is that the nomenclature ‘the Father’ is not used and that it is the first use of ‘son’ for Christ since 1 Cor 1:9. Paul has been using the title ‘Christ’ up until this point and so there is a significance to this change. The question is – to what scripture is Paul alluding? Psalm 2:7, “You are my beloved son”? Or Isaiah 9:6, “Unto us a son is given”? The context would suggest Ps 2:7 because it is used of the resurrection (Acts 13:33) and the priesthood (Heb 5:5-6; cf. Ps 110:4). Jesus is a priest-king and will reign from Jerusalem like Melchizedek, but he will deliver up this kingdom to the Father and be subject unto him.

Adam Christology

And so it is written, ‘The first man Adam became a living soul’; the last Adam [became] a life-giving spirit. Howbeit that was not first which is spiritual, but that which is natural; and afterward that which is spiritual. The first man is of the earth, earthy: the second man is from heaven. 1 Cor 15:45-47 (KJV revised)

This passage raises the question: why is Christ called the ‘last’ Adam? He is called the ‘second’ man but not ‘the second Adam’.[19] Genesis 2:7 is about ‘the man’ becoming a living soul, but Paul adds the name ‘Adam’. This picks up on the use of the name in v. 22, but there doesn’t seem to be any significance in the addition of the name in v. 45, except to enable the assignment of the title ‘the last Adam’ to Christ. Why?

The obvious suggestion is that Christ is the Adam of / for ‘the last things’; this proposal differs from Jesus’ avowal that he is ‘the first and the last’ (Rev 1:17, etc.) which picks up on the diplomatic titles in use in Hezekiah’s day (Isa 44:6; 48:12).[20] Since eternal life is given to those in Christ at the last judgment (v. 22), ‘the Adam of the last things [became] a life-giving spirit’ looks like typical Pauline phrasing. Jesus became a life-giving spirit in this sense with his exaltation, but he will be the Adam of the last things with the general resurrection and judgment, i.e. when the last things come about. The return of the Edenic state of affairs at the end is clear from Revelation 21-22. So it is that ‘first’ and ‘last’ are contrasted and Paul is careful to say that Christ is the ‘Adam’ of the last things and not the ‘man’ because as such he is a life-giving spirit whereas Adam was only a living soul. Certainly, ‘life-giving spirit’ expands “in Christ shall all be made alive” (v. 22), but ‘spirit’ in v. 45 is in apposition to ‘man’ and not ‘soul’.

When did Christ become or, alternatively, when will he be the ‘last’ Adam? Wright disagrees with J. D. G. Dunn on this question,[21] arguing that Christ was the ‘last Adam’ during his life on earth, citing John 5:21-24, whereas Dunn argues that Jesus became the ‘last’ Adam when he became a life-giving spirit after his resurrection and exaltation: “he became the ‘source’ of the Holy Spirit to all who believe”.[22] Our third counter-proposal is that Christ will be the ‘last’ Adam when he raises the dead, judges the dead and gives life to those who will inherit the kingdom.

Whether (with Dunn) Christ became the source of the holy Spirit after his resurrection and whether he gives a quality of life to believers in their mortal lives is not the topic in 1 Corinthians 15 – this is about resurrection and life: “As in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive”. The concept of life that Paul has in mind is not ethical; it is about existing – being alive. Furthermore, while it is true that Christ’s life on earth was ‘Adamic’ in its contrasting obedience (with Wright), this does not explain the use of ‘last’ in ‘the Last Adam’.[23] Christ will be the Adam of the last things when the last things are in play.

Dispensations

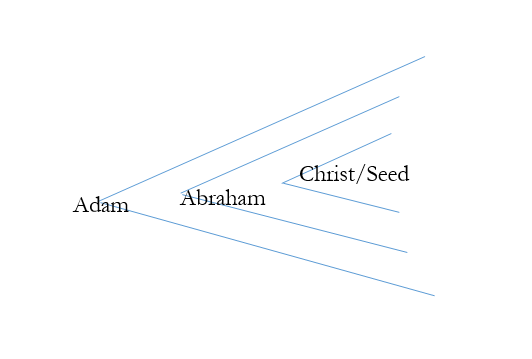

Dispensational models of history are usually linear and two dimensional: ages succeed ages in a straight line. If we change this approach to a three-dimensional one, what we have, to begin with, is a pair of cones. The largest cone is creation with Adam at the beginning; the counterpoint is Christ and the new creation. Christ was of Adam but not in Adam, and so the cone that begins with Christ, and is the new creation, it emerges from within the old creation. It is like a cone held in suspension inside the larger cone of creation. The point at which the new creation begins is the promise in Eden that a seed of the woman would deal a fatal blow to the seed of the serpent. The fact that Christ (this seed) did not come for thousands of years does not mean that the possibility of faith in Christ did not begin with this promise nor that a new creation on the basis of this faith was not possible. The visual advantage of the cone model is that the cone widens out from the federal head to include many people and many events.

This model is straightforward enough but what about Abraham and Israel? There is a correspondence between Adam and Abraham, there is a beginning and promises centred on a seed (Gal 3:16).[24] Christ was of Abraham but he did not just claim to have Abraham as his father, which means that we can apply the same model of the two cones. Faith in Christ has a new beginning with the Abrahamic promises and there have been those in Israel who followed that faith and those who have been unfaithful. However, although the faithful were primarily of Abraham, proselytes from outside Israel were always around. The important point here is that acceptable faith is further defined in relation to a new specification of the seed of the woman. It becomes about a more specific seed and a more specific land.

Since Abraham is the father of both natural Israel and of the faithful, the cones that begin with him are evidently set in suspension inside the cone that begins with the promise of the seed of the woman. The seed promised to Abraham is the seed of the woman, but the faithful now focus on the promises to Abraham. The difference with the giving of the Law, or even with Moses and the ‘birth’ of the nation of Israel from Egypt, is that these happenings do not yield a federal head. The father of the nation of Israel is not Moses, nor is their exodus from Egypt the origin of the nation; it is Abraham. The Law was added into the Abrahamic dispensation because of transgressions (Gal 3:19). The same point also applies to David and his seed even though Jesus is the seed of Abraham and of David (Matt 1:1). David is not the federal head of a people, but individuals can become heirs of the Abrahamic promises through baptism into Christ (Gal 3:27-29). Rather, the Davidic kingdom is a more refined specification of the dominion of the Last Adam, a dominion now specified in terms of kingship.

How you define an ‘age’ or a ‘dispensation’ is a matter of analysis. We have used a three-dimensional model centred on ‘headship’ (although the diagram is a plane figure) – our question has been, who is the father of a people? Hence, we have found three cones – an outer Adamic cone in which all are born (the old creation); an inner cone originating with the promise of the seed of the woman (the new creation) – those who have faith in this seed are born again. A further cone inside the Adamic cone stemming from Abraham and embracing the innermost cone that has its point of origin in the promise of a seed (singular, Christ) of the Woman and (now) Abraham (Rom 9:7).[25]

The gospel was preached to Abraham (Gal 3:8), and so whether the gospel is a dispensational beginning is the next question. The end of the Law is a matter of a change in sacrifices for those under the Law to the single sacrifice of Christ (Rom 10:4). This happens for Israel and within the Abrahamic dispensation. The fact that Gentiles are more explicitly included through preaching is foretold by the Prophets and particularly Isaiah in the terms of Hezekiah’s restoration after 701 BCE. But the apostolic outreach doesn’t signal a change in God’s election of Israel, because it has always been possible for Gentiles to be included among those who have the faith of Abraham. The ministry of the gospel is part of Israel’s history.

Commentators talk about the ‘age of the church’ and Christians focus on the church. They see a dispensational beginning in the proclamation of the gospel. They see the last two thousand years as the history of the church in all its vicissitudes. But it is possible that the facts of church history are conditioning how scholars read the New Testament. For example, they see the fact of the parting of the ways between the Gentile church and the Jews and read the New Testament to allow for this eventuality. However, contrawise, if the ministry of the gospel is part of Israel’s history, if the end of the Mosaic sacrifices is a matter for Israel, and if the outreach to the Gentiles is to share the faith of Israel, and no different in principle than Hezekiah’s outreach in the early 7c., then the parting of the ways would only go to show that the increasingly Gentile church became an apostasy from apostolic Christianity.

The expressions ‘New Israel’ and ‘new people’ do not occur in the NT; conceptually, to show that there is a ‘New Israel’ requires a different argument[26] to that which shows that there has been or that there is to be a renewal of Israel. The concept of the ‘new covenant’ is one that is embedded in Israel’s history (Jer 31:31; Heb 8:8, 13) and its Christian character maintains the church inside Israel.[27] The concept of a ‘new creature/creation/man’ is Adamic (2 Cor 5:17; Gal 6:15; Eph 4:24; Col 3:10, etc.) and we have shown that it has been around since the proto-evangelium (Gen 3:15).[28] We cannot argue from the fact of a new creation in Christ to there being a New Israel, or a new people of God, not on the dispensational model we have sketched. Hence, for instance, when Jesus appoints the twelve, this is to judge the tribes of Israel and not to be the heads of a New Israel (Matt 19:28; Luke 22:30).[29] The messiah is organizing Israel, not creating a new Israel; we might instead say that he is renewing Israel.

Peter addresses the Diaspora (1 Pet 1:1; cf. James 1:1) with the words,

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, that you may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. 1 Pet 2:9 (RSV)

This quotes Exod 19:6, addressing Israel. It is not the recognition of a new Israel, in the body of the church, but rather a reinforcement and an encouragement that the Jewish Christians in the Diaspora carried the great commission of their people on their shoulders.

This argument (and the choice we are presenting) goes to the heart of a common view in scholarship, namely, that the church (as a self-contained body) was the ‘last days’ restoration of Israel.[30] Our counter-argument is that the apostolic church was part of a restoration of Israel, but with the destruction of the Jewish state and the deportation of many Jews on the horizon in AD70, as prophesied by Jesus, the full restoration of Israel was never in prospect before the Second Advent and the restitution of all things (hence, Acts 3:19-22 and Simeon’s prophecy about the rise and fall of many in Israel, Luke 2:34).

The Restoration of Israel

The ‘restoration of Israel’ has been the subject of a lot of scholarly commentary. It is expressed as the view that Jews thought of themselves in ‘exile’ in their land and that their self-determination would be restored by their messiah.[31] It is developed using Isaiah’s restoration prophecies and often called a ‘new exodus restoration’. So, for example, M. M. B. Turner argues that Jesus’ mission in Luke and Acts through the Spirit is one of restoration.[32] This ‘exile and restoration’ theology might be true of some Second Temple authors,[33] but this is not how the NT writers viewed their situation or their message.

In general terms, there are several things that look like solid objections to this interpretation. First, the Jews are in the land and under occupation; this is not a metaphorical ‘exile’; people down the ages have sought liberation from occupation just as much as from exile. Secondly, John the Baptist and Jesus prophesied the end of the Jewish state (Luke 3:7; 21:23), so it is unlikely that they are engaged upon the full restoration of Israel. Thirdly, the Isaianic prophecies that the NT writers use were initially for those needing liberation after 701; liberation is the typology of Jesus’ ministry not restoration. Lastly, the ‘exodus’ and ‘new exodus’ typologies are about ‘release’, ‘departure’ and ‘journey’; they are not stories of restoration.

The restoration of Judah under Hezekiah after 701 is set against the background that the wrath of God was deferred (Isa 39:6; 48:9) – the destruction of Jerusalem was in the future (in 587). This is why Isaiah’s prophecies of liberation and renewal are the template for the apostles’ ministry which was carried out in the shadow of another destruction, namely, AD70. Hence, the restoration of Israel is explicitly thrown forward to the return of Jesus (Acts 3:19-22).

What do we mean by ‘restoration’? Any number of ideas could be put forward: (1) the self-determination of the nation; (2) the establishment of the Davidic monarchy; (3) renewal of infrastructure, cities, roads, and trade; (4) the rebuilding of the temple; (5) the bringing home of people held in captivity and/or deported to foreign places; and (6) the revitalization of society and culture.

In Isaiah’s day, post-701, the monarchy was in place and the apparatus of state had self-determination; but there was a need to rebuild the country’s cities and infrastructure; to bring home those who had been deported by the Assyrians; there was a need to rebuild and repair the temple and revitalize society and culture. Isaiah’s record reflects all these aspects of restoration, but they are not all relevant to apostolic times as the pattern for the ministry of the gospel.

New Testament scholars have proposed that the church is the restoration of (the people of) Israel, but there is no one-to-one identity because of the continued existence of natural Israel in the purpose of God. The preaching of the gospel and belief in Christ brings about ‘liberation and salvation’ of individuals who are then renewed by the Spirit, but they are part of the deliverance of Israel. The liberation and salvation of a people is the prerequisite for the work of restoration – this was true in Hezekiah’s day and true for when the kingdom will be restored to Israel (Acts 1:6).

Isaiah

In general terms, what is the usage of Isaiah in the New Testament? Jews in the Second Temple period sought the fulfilment of Isaiah in their own day. They were under occupation, and so liberation and salvation oracles were used to express their hopes. There are prophecies about an individual who would liberate them and there are prophecies about the liberation. In addition, Jews had ambition for their nation and sought its restoration and a position of power over the nations. Jesus stated that his kingdom was not of this world and that his servants would not fight, and this means that the political aspects of the restoration of Israel were not part of his mission, both before and through the apostles. The Isaianic prophecies that are applied to his mission, and then the apostolic mission, are those about liberation and salvation.[34]

As an example, we can look at the use of Isa 40:3-5 in Luke to describe the Baptist’s ministry.

The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain: And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it.’ Isa 40:3-5 (KJV)

As it is written in the book of the words of Esaias the prophet, saying “The voice of one crying in the wilderness, ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths straight. Every valley shall be filled, and every mountain and hill shall be brought low; and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough ways shall be made smooth; and all flesh shall see the salvation of God.’” Luke 3:4-6 (KJV)

The difference in Luke’s quotation with Isaiah is that he interprets the ‘glory of the Lord’ to be ‘salvation of God’, which draws upon Isaiah 35.[35] The context of Isaiah 40 is the aftermath of 701 and the need to liberate those held in captivity in Assyrian garrisons and by the local nations who had been part of the Assyrian confederacy.[36] The original context is political and military but this is applied spiritually by John the Baptist to the Jews of his day. There are seven correspondences in the typology that matches Isaiah’s day with the first century:

- The voice crying in the wilderness is that of a (1) messenger and one sent (2) before the Lord (v. 3; Mal 3:1)

- The Lord is coming from (3) the north in the person of the Arm of the Lord (Isa 41:25).

- The ‘wilderness’ is the (4) cities of Judah (vv. 10-11; Isa 51:3; 64:9).

- If[37] the people (5) repent, the glory of the Lord will be revealed.

- The glory of the Lord is (6) salvation and liberation (Isa 35:2, 4).

- All flesh (nations) would ‘see’ it ‘together’ and this would be the (7) creation of a garden of ‘trees’ in the wilderness (Isa 41:19-20, 23).

The application corresponds literally except for the salvation and liberation which is spiritual, which in turn makes the Roman occupation a metaphor for the people’s bondage to sin. The Baptist’s message from Isaiah is not about the restoration of Israel in any political sense, but it is about the salvation and liberation of people. The condition is their repentance which is demanded by the exhortation to prepare the way of the Lord.

The focus on people (rather than the apparatus of the state) is shown by the allusion to Isa 40:3, “to make ready a people prepared for the Lord” (Luke 1:17; cf. Acts 13:24), and the spiritual sense of ‘the Way’ is shown in the allusion, “for you will go before the Lord to prepare his ways” (Luke 1:76).

The use of Isa 40:3-5 addresses the people in situ – they are to repent and wait for the Lord. Luke also details the work of the deliverer from Isaiah. He records Simeon’s prophecy as a kind of prologue to his gospel. Simeon was waiting for ‘the consolation (para,klhsij) of Israel’ (Luke 2:25), and this ‘comfort’ for which he waited was the ‘salvation’ (Luke 2:30) of the people. He saw this in the infant Jesus. The allusion is to Isa 49:6, 13 and the Servant of the Lord, who was also to be a light to lighten the Gentiles (Luke 2:31), in order that he might take salvation to the end of the earth.

And he said, ‘It is too light a thing that you should be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob and to return (bwv) the survivors (rcn) of Israel; I will also give you as a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the land.’ Isa 49:6 (my trans.)

The original context of the oracle is the return of the deportees and captives, which would build up the tribes of Israel again. This political reality is not what Luke picks out in his record – he picks out salvation and the taking of light to the nations. The seventh century return of Judahites from deportation and captivity is a type of the ‘turning’ of the people to the Lord in response to the gospel. The involvement of the nations (‘a light to the Gentiles’) was to bring about the salvation of Israel in the seventh century. In the first century, the gospel is taken to the Gentiles to provoke Israel to jealousy (Rom 10:19; 11:11, 14) – it has the same purpose – to save Israel.

Commentators have sought to apply Isaiah eschatologically, but in the first instance, the prophecies have an immediate application to the political realities on the ground post-701[38] and then to the reality of the mission of John the Baptist, Jesus and the apostles. Hence, Pao is wrong when he characterizes Isaiah 40-55 by saying, “The dawn of the era of salvation and the deliverance of the people of God and Jerusalem/Zion forms the principle underlying Isaiah 40-55.”[39] Even on a post-exilic reading, this is wrong. There was no ‘era’ of salvation begun in the sixth or seventh centuries. Moreover, in the first century, we have the last days of Judah’s Commonwealth being played out; instead, the beginning of any new era[40] is linked to the return of Christ (Acts 3:18-22).

Liberation of captives and deportees and their salvation is one type from Isaiah 40-66, but salvation is also salvation from the ‘wrath to come’ (Matt 3:7; Luke 3:7; 1 Thess 1:10; 2:16). This prospect also has a typological basis in Isaiah, except there God’s wrath is deferred (Isa 39:8; 48:9) until what turned out to be the Babylonian Captivity.

Applying Isaiah in Second Temple Judaism

There are several ways in which Isa 40:3-5 is applied in the Second Temple literature,

(1) Applying Isa 40:3-5 to the return of exiles from Babylon is made in Baruch 5:5-7 (c. 2c. BCE),

Arise, O Jerusalem, and stand on high, and look about toward the east, and behold thy children gathered from the west unto the east by the word of the Holy One, rejoicing in the remembrance of God. For they departed from thee on foot, and were led away of their enemies: but God bringeth them unto thee exalted with glory, as children of the kingdom. For God hath appointed that every high hill, and banks of long continuance, should be cast down, and valleys filled up, to make even the ground, that Israel may go safely in the glory of God… Baruch 5:5-7

The Isaiah language is regarded as a metaphor for God facilitating the journey home – a metaphor describing God’s suppression of hostile nations on the route home.

(2) Similarly, in the Psalms of Solomon 11:2-6 (1c. BCE),

Stand on the height, O Jerusalem, and behold your children. From the east and the west, gathered together by the Lord. From the north they come in the gladness of their God. From the isles afar off God has gathered them. High mountains he has abased into a plain for them. The hills fled at their entrance. The woods gave them shelter as they passed by. Every sweet-smelling tree God caused to spring up for them, in order that Israel might pass by in the visitation of the glory of their God. Pss 11:2-6

However, the application here is to a general return from all points of the compass of the Diaspora.

(3) A different kind of application is in a description of the establishment of the kingdom in the Assumption of Moses (2c. BCE),

And the earth shall tremble: to its confines shall it be shaken: And the high mountains shall be made low and the hills shall be shaken and fall. Assumption of Moses 10:4

Isaiah’s figures are being used to predict the subjugation of the nations in the face of God’s kingdom. The same kind of use is found in 1 Enoch 1:6, “And the high mountains shall be shaken, And the high hills shall be made low, and shall melt like wax before the flame.”

(4) Another kind of use of Isaiah is that in the Qumran sectarian document 1QS.

And when these become members of the community in Israel according to all these rules, they shall separate from the habitation of unjust men and shall go into the wilderness to prepare there the way of him; as it is written, ‘Prepare in the wilderness the way of…, make straight in the desert a path for our God’ (Isa. Xl, 3). This path is the study of the Law which he commanded by the hand of Moses, that they may do according to all that has been revealed from age to age, and as the prophets have revealed by his holy Spirit. 1QS 8:13-16; cf. 9:16-21

This interprets ‘the Way’ in Isaiah in ethical terms and supports the ascetic lifestyle of the Qumran community. The political overtones of the ‘hills’ and ‘mountains’ in other texts is not picked up, nor any journeying from foreign lands. In fact, disciples go away from the land into the wilderness.

Taking the above applications, (1) – (4), and comparing them with Luke, it would seem that the Baptist’s use of Isaiah is not too dissimilar to that of the Qumran community. Scholars have often made a comparison with John the Baptist and Qumran. His ethical imperative is tied to the coming of a liberating lord (in keeping with Mal 3:1), rather than the establishment of a new age (the kingdom). The ethical dimension is shown in Acts 13:10, “You son of the devil, you enemy of all righteousness, full of all deceit and villainy, will you not stop making crooked the straight paths of the Lord?” The application of Isaiah to the return of exiled Jews or to the coming home of the Diaspora is not part of the Baptist’s declaration.

The Exodus

The ‘exodus’ could be narrowly defined to include just the deliverance of Israel from Egypt up to and including the crossing of the Red Sea; it could be more broadly defined to include the two-year journey to the land or the whole of the wilderness wandering period; and it could include the crossing of Jordan and arrival in the land. Turner includes all these elements as they have been reconfigured in Isaiah 40-55, and he also adds the element that the ‘new exodus’ embraces the goal of a “restored Zion/Jerusalem”.[41]

Pao has a similar comprehensive understanding of the motif of the ‘new exodus’. Concluding a discussion of Isa 40:1-11, and noting the military language of vv. 10-11, he states that “This language evokes the Exodus paradigm in which God delivers and restores his people”.[42] The question can be asked, however, as to whether ‘restoration’ is an exodus paradigm. Certainly deliverance and journey is involved, but Israel was not the ‘people of the land’ before the exodus; a small family went down into Egypt and a nation came out of Egypt. The nation, as such, was not restored to the land in the traditions of Genesis-Exodus; it is better therefore to describe Isaianic typology in terms just of a “new exodus deliverance” (e.g. Isa 48:20-21; 51:9-10). What we need to do, however, is distinguish the use of Isa 40:3-5 to describe the Baptist’s ministry from the typology of a new exodus deliverance.

Mark combines Isa 40:3 with Mal 3:1 which in turn echoes Exod 23:20,

As it is written in Isaiah the prophet, “Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, who shall prepare thy way; the voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight’…” Mark 1:2-4 (RSV)

Behold, I send my messenger to prepare the way before me,[43] and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple; the messenger of the covenant in whom you delight, behold, he is coming, says the Lord of hosts. Mal 3:1 (RSV)

Behold, I send an angel before you, to guard you on the way and to bring you to the place which I have prepared. Exod 23:20 (RSV); cf. Exod 13:21-22

The typology in these texts is different. The difference between Exod 23:20 and Isa 40:3-5/Mal 3:1 is one of leading as opposed to coming. Further, Israel are led along a way in the exodus; in Isa 40:3/Mal 3:1, the exhortation to the people is to prepare a way. The messenger and the people prepare a way for the lord. The way across the wilderness coming to a people is a different way to that which the lord takes leading a people to a prepared place.

A way for coming to the people does not feature in the exodus and we cannot therefore describe the way of Isa 40:3 as a ‘new exodus’ way. God does not need an exodus; people need an exodus! This does not mean that Isaiah does not allude to the leading of Exod 23:20 in other ‘way’ texts.

(1) So, for example, Isa 52:12, “For you shall not go out in haste, and you shall not go in flight, for the Lord will go before you, and the God of Israel will be your rear guard” is an obvious allusion. This text refers to the Levites re-acquiring the vessels of the Lord on the borders of Egypt.[44] The exodus allusion is not ‘travel’ based (crossing a desert; a way in the wilderness; crossing water); it is not describing a journey. The allusion is about leaving (‘go out’) and protection on a journey about to start (‘before/after’). This is not the ‘way’ of Exod 23:20.

(2) Another exodus way allusion refers to the crossing of the Red Sea, “Thus says the Lord, who makes a way in the sea, a path in the mighty waters…I am about to do a new thing…I will make a way in the wilderness” (Isa 43:16-19). The phrasing here (lit: ‘the one making’ – a participle) indicates that the way and the path are being made in Isaiah’s day; the allusion is to the crossing of the Red Sea on dry land, but the claim is that this was being re-enacted in a figurative sea (cf. Isa 44:27). The description of the waters as ‘mighty’ uses the same adjective that was used to describe the east wind that separated the waters of the Red Sea (Exod 14:21). The sea and the waters are the ‘nations and peoples’ through whose territory Judahites had to cross as they fled from Babylon. In particular, the ‘mighty waters’ are those of ‘the river’ that was Assyria (Isa 8:7; 28:2, 17), while the sea is more generally the nations (Isa 17:12-13; 57:20). Again, this allusion is not the ‘way’ of Exod 23:20; it is the ‘way’ across the Red Sea.

(3) A clear exodus motif is used in Isa 51:10, where we shift from the creatures of v. 9 to ‘the sea’:

Art thou not it which hath dried the sea, the waters of the great deep; that hath made the depths of the sea a way for the ransomed to pass over? Isa 51:10 (KJV)

The ‘great deep’ is an equivalent metaphor for ‘the sea’ that is the area of the Ancient Near East, and it is an allusion to Noah’s Flood,[45] continuing the motif of the Assyrian Confederacy overflowing Judah (Gen 7:11, ‘great deep’; Isa 8:7). The allusion to the ‘drying up’ of the Red Sea is from Ps 106:9; the verb is not used in the exodus account. The ‘Arm of the Lord’ dried the sea and Moses’ action in raising his arm over the Red Sea (Exod 14:16; cf. Deut 4:34) is a natural typological basis for that term of reference (cf. Deut 4:34, “with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm”). The ‘drying up’ of the sea is a common figure for what God does to nations (Isa 37:18, 25 ‘waste’; 44:27; 49:17 ‘waste’; 50:2; 60:12 ‘waste’). This ‘drying up’ of the sea was prophesied in Amos 7:4 with a different image: a fire ‘devoured the great deep’. The drying up of the sea symbolizes what God does to the nations round about Judah and in Mesopotamia. So, the withdrawal of Assyria from the west (its western army destroyed), and the Babylonian rebellion in the east, requiring Sennacherib’s attention, is the ‘drying up’ of the sea, and this afforded the opportunity for captive Judahites from all points of the compass to return to the land; the destruction of the Assyrian army and the consequent chaos and disarray in the west afforded Judahites various routes home.

The next figure, ‘depths of the sea’, refers to the sea-bed and even the mire of the sea-bed (Ps 69:3, 15). A way had been made by dint of the fact that the sea had been dried. This is a way for the ‘redeemed’ or ‘ransomed’ to pass over; the plural occurs elsewhere only in Isa 35:9. This is not the ‘spiritual’ concept of ‘the Way’ that we find in Isaiah, but the making of a way (many ways) back to Judah. Exactly where the redeemed come from is not stated. Also, this is not the ‘way’ of Isaiah 40 which is about the Lord coming to the cities of Judah.

It is because God has made a way by removing Assyria (and engaging Sennacherib in Babylon) that ‘the redeemed shall return’ from Babylon (and elsewhere):

Therefore, the redeemed of the Lord shall return, and come with singing unto Zion; and everlasting joy shall be upon their head: they shall obtain gladness and joy; and sorrow and mourning shall flee away. Isa 51:11 (KJV)

This quotes or reiterates Isa 35:10[46] which follows on from, or is coincident with, the ‘year of recompence’ (Isa 34:8). This ‘year’ involves action against Edom (Bozrah, Isa 34:6) which is now ongoing (Isa 63:1). The joy that will be ‘upon their heads’ is an obvious inversion of the more common demonstration of lament in putting dust upon the head (Josh 7:6; Lam 2:10). They are ‘the redeemed’ or ‘the ransomed’ because a ‘price’ has been paid for them (Mic 6:4; Isa 1:27).

(4) The texts that come closest to Exod 23:20 are those which are simply about a way across the wilderness (i.e. they are not about the crossing of the Red Sea). For example,

And I will lead the blind in a way that they know not, in paths that they have not known I will guide them. I will turn the darkness before them into light, the rough places into level ground. These are the things I will do, and I will not forsake them. Isa 42:16 (RSV)

And I will make all my mountains a way, and my highways shall be raised up. Lo, these shall come from afar, and lo, these from the north and from the west, and these from the land of Syene. Isa 49:11-12 (RSV)

Pao fails to mark the distinctions in ‘the way’ figures of Isaiah, 40, 42, 43, 49, 51 and 52, and he coalesces the texts into an amorphous whole. He states, “The fact that ‘the Way’ signifies the salvific act of God on behalf of his people explains why ‘the Way’ is prepared for both Yahweh and his people.”[47] This explains nothing of the sort: there is a fundamental difference between (1) the way across the wilderness; (2) the way across the Red Sea; (3) the departure from Egypt; and (4) and a way that the people prepare for the coming of Yahweh. Crucially, the Baptist’s ministry is described using Isaiah 40 – the way that the people prepare for Yahweh, and this is because the voice crying in the wilderness is a messenger that heralds the coming of the Arm of the Lord to deliver the people; this is not an exodus paradigm.

Identity

It is well-known that ‘the Way’ is a term of identity for the early Christians (Acts 9:1-2; 19:9, 23; 22:4; 24:14, 22). The term serves to distinguish Christians over against those who are not believers (Acts 19:9), but the expression is not associated with characterizations such as ‘true people of God’; those of the Way are believers in the coming kingdom of God, but ‘the Way’ is how they are distinguished within communities of their own people,

But this I admit to you, that according to the Way, which they call a sect, I worship the God of our fathers, believing everything laid down by the law or written in the prophets… Acts 24:14 (RSV)

The use of the term ‘sect’ shows that Christians were distinguished, but were part of Israel. A sect can consider that they have ‘the truth’ and are the true heirs of the teaching of the Scriptures, but this doesn’t mean that they considered that they were a new people apart from Israel and now set against them in the purpose of God. The point here is that the narrative detail surrounding use of ‘the Way’ doesn’t support the stronger thesis that Pao expresses by asserting, “With this assertion, the Christians claim to be the true people of God and the true continuation of ancestral traditions.”[48] The problem here is not that a sect claimed to have the truth and thus claim to the ‘the Way’, but rather that Christians claimed to be the true people of God in contrast to Israel.

The terminology of ‘the Way’ is based in Isa 40:3-5 in which the people are exhorted to prepare a way for Yahweh. We have noted above that this is not an exodus typology (contra Pao); equally, Isa 40:3-5 is not the beginning of a new age of salvation, nor is it redefining the people of God – it only serves to define the faithful within the people of God. We saw above a similar use of ‘the Way’ as an identity marker in 1QS 9:16-21, also based on Isa 40:3-5. Josephus’ social analysis of his people includes various sects, but, crucially, they are set within the body of the nation, and he includes the Essenes (Ant. 13.174).

Conclusion

The two-dimensional model of ages succeeding ages in a linear fashion is misleading (Ante-Diluvian, Patriarchal, Mosaic, Christian). It can give the impression that the Mosaic Age has been succeeded by another age; or that Israel is no longer relevant in the purpose of God. We might describe the latest age as the Age of the Church or the Kingdom Age, or just simply the New Age. A common proposal is that the Mosaic dispensation has been replaced by the dispensation of the Gospel; this is a gospel of preaching about a coming kingdom. But the preaching of the gospel is a beginning set within the Abrahamic framework as our model makes clear. This model is not replaced, nor has it come to an end – the kingdom age is part of the Abrahamic cone of history and serves as its conclusion. In fact, the original Adamic cone also comes to an end at this time when the last enemy is destroyed – death – at the conclusion of the kingdom (1 Cor 15:26).

How then should we place the resurrection of Christ? It is the actual beginning of a new creation, a spiritual basis of life. The contrast is with the old creation with its first man, but this creation is neither of Adam nor in Adam, it is solely in and of Christ who is a life-giving spirit. Clearly, the resurrection is of heaven and from heaven, whereas the ages of Adam are of the earth. Those who are resurrected will be ‘the heavenlies’ over the restored kingdom of God on earth (1 Cor 15:47-48; Eph 2:6). Thus, because the resurrection is ‘of heaven’, it is not part of the dispensational history of the earth.

[1] N. T. Wright, The Climax of the Covenant (London: T & T Clark, 1991), xi.

[2] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 1, 13.

[3] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 2; discussed and rejected by T. Gaston, “Some Thoughts on 1 Corinthians 8:6 and the Shema” CeJBI 10/1 (2016): 63-68. Also see J. Adey, “One God: The Shema in the Old and New Testaments” in One God, the Father (ed. T. Gaston: Sunderland: Willow Publications, 2103), 26-39.

[4] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 3.

[5] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 14; “Paul has not, however, simply substituted Christ (and his people) for the nation of Israel in current Jewish expectation.”, 36.

[6] The incidental point here is that the Abrahamic promises and the patriarchal stories are told with allusions to the account of man in Genesis 1 and plausibly post-date the tradition in Genesis 1. On this see A. Perry, Beginnings and Endings (2nd ed.; Sunderland: Willow Publications, 2006).

[7] See A. Perry, Isaiah 40-48 (3rd ed.; Sunderland: Willow Publications, 2015), 325-327.

[8] See A. Perry, Isaiah 49-57 (1st ed.; Sunderland: Willow Publications, 2015), 175-177, shows that Isaiah 55 is pre-exilic and refers to the monarchy; contra Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 23, “the kingless state of God’s people”.

[9] For an introduction see L. Goppelt, Typos: The Typological Interpretation of the Old Testament in the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982).

[10] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 26.

[11] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 26.

[12] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 36.

[13] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 37.

[14] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 38.

[15] A. Perry, “Psalm 110” CeJBI 2/2 (2008): 24-29.

[16] These are set out in J. Adey, “Psalm 110” CeJBI 2/3 (2008): 38-42.

[17] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 29.

[18] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 30, has no credible answer to this point. He says, “It is of course true that if vv. 23-8 were all we had of Paul’s christology we might well draw some such conclusion. But there is a tell-tale sign that Paul is aware of the problem, and is building in to his exposition here…a hint of the fuller christology which we will see in other passages.” The so-called ‘hint’ is Paul’s use of ‘son’ for Christ, but Wright is just trying to deflect the problem of the passage and projecting his own problem onto Paul. Paul’s Christology is typological and consistent; Wright’s incarnational Christology is the one with the ‘problem’.

[19] Wright doesn’t see how ‘first’ is related to ‘last’ and makes the mistake of saying “The task of the second Adam was not merely to replace the first Adam.”, The Climax of the Covenant, 37.

[20] The diplomatic titles are used in Isaiah in the context of political policy, i.e. they are titles of diplomats who propose policy and predict what will happen in the affairs of a nation. Hence, Yahweh appropriates these titles to Himself as the one who can truly make prophecy. And so they are used by Christ in the Apocalypse because that is his revelation of what is shortly to come to pass.

[21] Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 33.

[22] Contra J. D. G. Dunn, Christology in the Making (London: SCM Press, 1980), 107.

[23] Contra Wright, The Climax of the Covenant, 39. This also explains why the Jewish Scriptures do not present Israel as a ‘Last Adam’ (39).

[24] See Perry, Beginnings and Endings, 151-170.

[25] Humans think of time in a linear way, but the model here is of the Deity inserting and wrapping the Abrahamic cone around the innermost cone of the seed of the woman.

[26] For example, D. W. Pao offers a common argument: “Similarly, in the development of the identity of the early Christian movement, the appropriation of ancient Israel’s foundation story [the exodus] provides grounds for a claim by the early Christian community to be the true people of God in the face of other competing voices.” Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2000), 5, 33, 39, (my emphasis).

[27] The implication of this is that, with the withdrawal of the Spirit, Christ has no church on earth today, but rather there are individuals who have gathered together believing in the Abrahamic and Biblical Unitarian faith left behind by the apostles.

[28] There is a tension between the concepts of a ‘new creation’ and ‘restoration’. If we say that there is a new Israel, we can hardly say that there has been a restoration of Israel.

[29] This typological use of the twelve has been emphasized in scholarship; see Goppelt, Typos, 107-110; J. P. Meier, “Jesus, the Twelve and the Restoration of Israel” in Restoration: Old Testament, Jewish, & Christian Perspectives (ed. J. M. Scott; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2001), 365-404.

[30] For example, E. P. Sanders, Jesus and Judaism (London: SCM Press, 1985), 77-119; M. M. B. Turner, Power from on High: The Spirit in Israel’s Restoration and Witness in Luke-Acts (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995), 244-249; R. I. Denova, The Things Accomplished Among Us (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1997), 231, and M. Fuller, The Restoration of Israel (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2006).

[31] This historical reconstruction has been popularized by N. T. Wright since the 1980s, but it appears in many scholarly monographs, for example, it appears in Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus, 30, 34.

[32] Turner, Power from on High, 314-315; the restoration program “is largely complete by Acts 15”, 419.

[33] The evidence is set out in C. A. Evans, “Jesus & the Continuing Exile of Israel in Jesus & the Restoration of Israel (ed. C. C. Newman; Downers grove, IL: Paternoster, 1999), 76-100.

[34] There are many studies ‘out there’ of the use of Isaiah in parts of the NT, but an introduction is afforded by S. Moyise & M. J. J. Menken, Isaiah in the New Testament (London: T & T Clark, 2005).

[35] Later allusions to Isa 40:3 through the term ‘salvation’ are Acts 13:26; 28:28.

[36] This is set out in Perry, Isaiah 40-48, chap. 5.

[37] The conditional is implied in ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord…and the glory of the Lord will be revealed’. If they did not ‘prepare’, the glory would not be revealed.

[38] This is the social and political nature of prophecy – see M. de Jong, Isaiah among the Ancient Near Eastern Prophets: A Comparative Study of the Earliest Stages of the Isaiah Tradition (VTSup 117; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2007).

[39] Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus, 46.

[40] To establish a new ‘era’ we require the use of time-concepts: in Acts 1:7, the ‘times’ are reserved in the Father’s hand; in Acts 3:20-21, Jesus is said to be in heaven until ‘the times’ of the restitution of all things.

[41] Turner, Power from on High, 247.

[42] Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus, 51.

[43] In Malachi, the first person is used, ‘he shall prepare the way before me’ but in Mark it is the second person. The quotation of Mal 3:1 by Jesus (Luke 7:27) uses the second person and this explains Mark: the variation of person identifies the lord who will come. The messenger is the voice crying in the wilderness.

[44] Perry, Isaiah 49-57, 128-133.

[45] The expression ‘great deep’ does not occur in Genesis 1; this is not the target for the allusion.

[46] It ties the two chapters together as from the same context.

[47] Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus, 53.

[48] Pao, Acts and the Isaianic New Exodus, 65.