Background A Faithful Tradition

In the last article we showed how there was among certain descendents of Abraham a tradition of worship of the One True God, quite apart from the institutions of the nation of Israel. Our first example of one of these ‘Bene Kedem’ who was a faithful worshipper of God is Job. There is no doubt that Job was a worshipper of the True God, for the Scriptures tell us so; equally, there is no doubt that Job was not an Israelite. Since the promises to Abraham were passed on to Israel as a nation through Isaac and not Ishmael (father of the Bene Kedem), on what basis could Ishmael’s descendants such as Job worship God?

Our answer is that there could be one basis only for this worship – a sharing of the faith of Abraham. There is no other basis. The Bene Kedem could have been given no Law such as Israel received, by which they as a nation could have been called God’s people. For we are expressly told that Israel alone was God’s people, God’s holy nation. Anyone else who wished to worship God would have to do so on exactly the same basis as ourselves, believing the Abrahamic promises, understanding as individuals that salvation could only come by faith,and faith in an Israelite seed, son of promise through Isaac. Their only difference from ourselves in this would be that we see Jesus in history, and they saw him in prophecy. In later articles we propose to show that through the centuries some among the Bene Kedem did indeed have this faith; and here we look at Job from this point of view.

If it is understood that Job could not have been under law as the Israelites were under the Law of Moses, then one of the most common theories about the book of Job is seen to be impossible. It cannot be a treatise on faith and works, since the Bene Kedem could not have been put by God under a system of works. Job must have come to God through faith, and the book of Job must be seen with this in mind.

If the book is seen against its proper Arab background, it will be seen that certain other commonly held theories are equally out of place. Most of these theories arise because this essentially eastern book is interpreted in western terms. For example, some see it as a treatise on general human suffering, a working out in philosophical terms of the reason for pain and trouble. Some look on it as a literary comment on life as it is, without a moral message. Some are certain that it is nothing but a piece of fiction, since they believe that no one would actually talk in poetry. To propound all these ideas is to think like Greeks, like Europeans – not like Semites, and the book is a Semitic book. In order to understand the Semitic mind a little better, we need to go more closely into the background of Job and his people, before looking at the actual content of the book. This article on Job is in two parts, the first dealing with Job’s background, the second (in the next issue) dealing with the message of the book.

Job’s Background

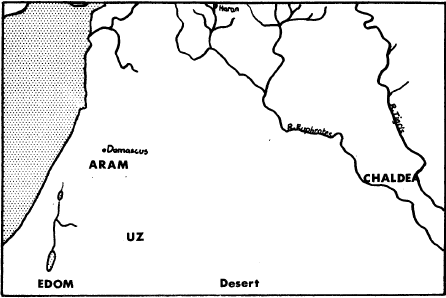

In the map you will see the probable position of the land of Uz. The Septuagint version of the book of Job adds as a gloss that the land of Uz was close to Edom and Arabia; the first Uz meationed in the Bible was a son of Aram whose lands surrounded the city of Damascus; and so it seems reasonable to place the land of Uz on the edge of the Arabian desert, north of Edom, and south of Aram (Syria). The fact that Job suffered attacks both from Chaldeans from the east, and Sabeans from South Arabia, supports this theory on the place of Job’s dwelling.

Uz, then, was part of the circle of steppe lands surrounding the Arabian desert, dwelling place of the sons of Abraham who were not descended from Isaac. The land was suitable for cattle, provided a nomadic life was lived; but the greatest of the men of this area would earn their living by the caravan trade, since they lived on the great highway from South Arabia to Damascus.

Job himself was called the greatest of the men of the east; moreover he lived in a house (42:11) and so did his sons. Though he kept herds (presumably in the lands outside his city), the fact that he possessed three thousand camels makes it clear that he was also a merchantman. He would, no doubt, live in one of the large caravan cities of the area, in which he was a leading citizen (29:7-8). It was a city which possessed nobles and princes (29:9-10), and was therefore no mean village. Like Abraham and other patriarchs, Job acted as priest for his family (1:5).

Job was a believer in God, and so were his friends; but he lived in an area where the traditional gods of Arabia, the sun and moon, were also worshipped (31:26-27). The likelihood was that he and his friends were all descendants of Abraham, and still clung to the faith of their father, amid the idolatry of those who had originally lived in the North Arabian lands. Job and his friends normally use the ancient form of the name of God, ‘El’, or ‘Eloah’, the form which continued to be used in the area for centuries afterwards, becoming ‘Allah’ of the Moslems.

Heritage from Abraham

Job and his friends, then, were almost certainly descendants of Abraham’s sons by Hagar and Keturah. These had all left the land of Canaan, and moved into the North Arabian steppe lands, to become the fathers of the North Arabians. Since the time in which the action of the book took place was not far removed from the time of Abraham, it is not surprising to find the actors living much as Abraham lived, and even thinking like Abraham thought. This last point we hope to examine in more detail in the next study.

Virtually from the time of Abraham the history of those descended from Isaac, and those descended from Ishmael and the sons of Keturah, became separate. However, the mode of life of Abraham was eventually followed not by the children of Isaac, but by those of Ishmael and Keturah. The sons of Isaac, by going into Egypt, became settled town and country dwellers; while the others continued to live the kind of life lived by Abraham – the life of a nomad.

The two different ways of life were forced on these descendants of Abraham by the type of land in which each group dwelt. Isaac’s descendants, living in the fertile agricultural lands of Goshen, turned to settled dairy farming, and eventually were forced into the cities to become slave labour. On the other hand, the meagre steppe lands surrounding the fertile crescent kept Abraham’s other descendants fixed to the pattern of life practised by Abraham himself.

This had the effect of virtually fossilising the culture of Abraham on his steppe-dwelling sons for so long as they lived in this area. Not only Abraham’s way of life, but even Abraham’s form of speech, became preserved more rigidly among the nomads than among the children of Israel in Egypt (who adopted Egyptian words and constructions into their language, and later assimilated some from the Canaanite nations of Palestine). Nevertheless, for many years the two languages continued to be understood by those from either branch For example, Moses appears to have had no difficulty in understanding the Ridianite speech of Jethro.

Arabian Oral Culture

The nomadic way of life does not encourage literacy. The wandering life does not mix with the acquisition of large, heavy books; nor is the need to write strongly felt. We have no record which suggests that Abraham could read or write (though this is not impossible). It is the town life which encourages writing, and originally commerce provided the drive to literacy. Records were necessary in order to keep a tally of transactions; it was only later that writing began to be used for recording religious details; and later still – much later, the need was felt to make records of cultural compositions

Where there is little or no literary culture, there is certain to be a strong oral culture. All historical information goes to show that while the North Arabians have always had a strong oral tradition, only very late in history (800 – 900AD) did some of this tradition find its way into writing. The great holy book of the North Arabians, the Koran, though uttered by the “prophet” Muhammad round about 600 – 700 AD, was not written down until some years later.

The culture of the North Arabians, then, was an oral culture. That is, any composition of importance was recited verbally, and then remembered and passed on to others.

In this kind of culture, two important things occur. First, the form of words used in oral culture tends to be poetic. This is because sentences with rhythm and verbal connections are much easier to remember than flat prose. A people who have only an oral culture tend to be fluent poets, to speak poetically in their normal speech, and to have poetry ingrained, as it were, into their very minds. This addiction to poetry has made the Arab people famous both for the fluency of their actual speech, and for the beauty of their more formal compositions. Poetry, when once ingrained in the life of a people, takes an extraordinary time to be eradicated. For example, long after Israel in the land were almost fully literate as a people, the prophets and prophetesses still used occasional poetic forms for their Spirit-guided utterances. This poetic turn of speech was not a conscious composition, but flowed naturally from inspiration. Not until New Testament times did this natural poetic fluency forsake God’s people. There is hardly a fragment of poetry in the New Testament – but, of course, it was intended for a literary, proiaic people.

The second important result in the life of a people of oral culture is that prodigious memories are developed. Their culture depends on memory – therefore memory is trained to make use of culture.

In this, we are not to think that a culture based on poetry and memory is inferior to one based on writing and literacy. After all, memory is the basis of meditation – surely, the failure of so many westerns Christians to meditate in the same sense as Old Testament believers, is due to this lack of remembered Scripture. David appears to have had the whole of the Law of Moses off by heart, and so was able to study it within his own mind in the night watches – and what a wealth of poetry this meditation inspired! On the other hand, ‘meditation’ as supposedly practised by many ‘Christian’ westerners is often no more than introspective emotionalism, unrelated to the truths of Scripture.

Indeed, an oral culture may be superior to a literary one, in the sense that while the knowledge of the literary man resides in books and writings, that committed to memory is in the mind. A little more effort of memory might help present day Christians considerably. It is not uncommon for a Christadelphian to speak enthusiastically of a study-address he has heard, and how the views of the speaker were entirely convincing; and when he is asked, “What did the speaker say?” there is an embarrassed silence, followed by a swift defence “Wells it’s all in my notes…….. ” This

is not to say we think the speaker should address his audience in poetry, however!

The speeches of the book of Job bear all the signs of having been produced by oral culture. This book (like all the poetic utterances in the Scripture) was surely never composed by a man sitting down sucking a pencil (or stylus or what have you). This is no artificial, formal type of composition. Its measured cadences, its force, its repetitions balanced against earlier statements-all this is clearly the work of a people who were naturally used to speaking in poetry, and its very sincerity suggests that it originated on an actual occasion. Job’s first elegaic lament is exactly what one would expect a man of his background to utter naturally from the deep poetry of suffering.

Our picture, then, of Job is of a man of the east, wealthy in flocks and herds, and in merchandise, a man who has lived in an important caravan city on the great north-south route in the east. This man suffers untold disasters and hardship, and when visited by terrible disease has to go outside the city to the place where rubbish is burnt, and to scrape himself with pieces of broken pot which lie on the heaps. Meanwhile, the whole of the East is agog with the matter. Why has this awful thing happened to Job? What has he done to deserve it? Above all, is the God Job worships really a living God – or is Job dwelling in a fools’ paradise,holding an empty hope to his shrivelled bosom? So Job’s three friends hear of the disaster, and come to mourn with him. The story moves with the slow tempo of the nomadic life of the east. They fix a time to meet, and then travel together from their meeting point to visit Job. When they find him, they are appalled, and sit down in silence.

Here, also, the men of the city come. For they are puzzled, not knowing whether Job is right or wrong, whether Job’s God is to be worshipped or not. And so we can picture men coming out to join the group, expecting the visit of the friends to resolve in some way the whole matter. This matter is worked out in public – Job is a public figure, whom God uses to show certain things – but these have to be worked out slowly, maybe even over many days, while men discuss, and Job continues to suffer.

The first part of the play (a living play, actually played out by men) is the discussionbetween Job and the friends, which crystallizes the difficulty, but does not solve it. Then from the back of the group of watchers a young man stands up, who carries the discussion one stage further. This man has been listening closely – he is himself a prophet with the great gift of instant memory, and he has carefully memorised the whole of the speeches up to that time. Now, under pressure of the Spirit of God, though young, he speaks out, and confounds the older men who had condemned Job, and yet had found no answer to his problem. Last of all, a whirlwind comes up from the desert, and out of that whirlwind a voice of thunder which comes to Job in a distinct voice; it is the voice of God. We do not believe the others necessarily also heard the Voice – like Paul’s companions, they may have heard the thunder, and not have been able to distinguish the words. But the message is clear enough when Job rises before the prostrate friends and makes atonement for them.

The actual meaning of the book we propose to look at in the next study. Two further details we examine now – the language of the book, and the means by which this essentially Arab book came into the Jewish canon.

Forms of Speech

We have said already that this is not a western book, argued out logically in western fashion, but an eastern book which was originally part of an oral culture. An Arab, even today, not only expresses himself poetically, but has not the brutal directness, the love of logical simplicity, of the Greek taught mind. It is necessary to remember sometimes that the problems of the book are often approached obliquely – for example, Job in his first speech begins by cursing not himself, or his father or mother, but the day he was born. Instead of saying “I wish I had never been born” he describes the events of his birth, and bemoans the fact that some accident did not occur at the time. This oblique kind of thought continues through the book; and misunderstandings sometimes arise when these statements are taken too directly.

For example, there are several places where Elihu appears to be making general statements about mankind. See for example, ch.32:8, “There is a spirit in man: and the inspiration of the Almighty giveth them understanding”

Elihu appears to be claiming that all men are inspired by God; yet he has just implied that the friends have failed to teach wisdom. In fact, the only sensible way to read this verse is to take it as an oblique reference to himself; he is saying, politely, “Some men know the right answer, because they have been inspired by God”, implying that he himself is the one inspired. (It may be worth noting that Muhammed does exactly the same kind of thing in the Koran.)

Another example may be seen in ch.33. Here Elihu appears to be describing ‘man’ in general being instructed by God (verse 14-22). Yet it is clear from the description of-the ‘man’ that he is not dealing with the case of man in general at all, but specifically describing Job’s own case – not directly, but obliquely, in the third person. The ‘man’ he is describing is one who has been brought almost to the grave with suffering; the most that we can concede is that a ‘man in Job’s case’ is being spoken of.

Western commentators, to whom philosophising about man in general is almost second nature, have picked on many of these ‘man’ statements and taken them as general philosophy. We suggest that the book was never intended to be read in this way, and that general philosophical statements were foreign to the type of persons who speak here – people to whom human relationships, and the relation of a man to his God, were the means by which wisdom was taught. This kind of teaching was the way in which Abraham learnt about resurrection – and we suggest that Job, like Abraham, understood the truth about this without having to set it out as a logical statement of faith. But this is to be looked at more closely next time.

Job and the Hebrew Scriptures

The question now remains; if this book is part of the religious culture of the Arab peoples who worshipped God like their father Abraham, then how did it come to be included in the Hebrew Scriptures?

We suggest that, as far as the Arabians were concerned, the poem of Job was probably never written in a book ( the reference to ‘book’ in ch.19: 23 seems to mean ‘graven on a monument’ – one of the few uses of writing commonly employed by the ancient Arabians); but it was remembered first by Elihu, and then recited from mouth to mouth by the priests and faithful men of the children of the east. The words of Job and his friends would be carefully memorised, and recited word-for-word, but the surrounding circumstances might well be described and told by the reciter in his own words, sometimes suiting his account to his audience. This would account for the difference in language between (a)the poetry of the speeches, and (b) the accounts of how it all happened, and how it ended. As time went on, the speeches would appear increasingly archaic; but the beginning and end of the tale would always be told in the normal language of the time.

However, the language of the prologue appears to be Hebrew rather than Aramaic. The word ‘Yahweh’ is used rather than ‘El’, or ‘Eloah’, the more common Arabian terms; in fact, it appears that the story of Job is being told for the benefit of Hebrews.

Our suggestion as to how this poem came into the literature of the Israelite people, then, is that in the time of Solomon, when Israel virtually ruled over the whole of the Arabian lands, Solomon gave audience to many of the wise men of the east in order to exchange wisdom with them (see 2 Chron. 9:22 & 23; 1 Kings 4:30). We suggest that on one of these occasions an Arabian was asked to recite the story of Job. In deference to his host, the reciter told the first part of the tale in Hebrew; but when it came to the speeches, he did not feel justified in putting these in ‘modern’ dress, and so recited the speeches of Job, his friends, Elihu and God, just as they had once been spoken, in the language of Abraham himself, a language which might sound archaic to the men of Solomon’s court, but which could still be understood. And Solomon, impressed, commanded his scribes to write down the whole story, and to keep it with the sacred records. This would account for its position in the canon, among the wisdom of David and Solomon’s day.

The fact of its inclusion meant that it was accepted by the Israelites as a divinely inspired record – and, indeed, underlines the truth that God required its preservation for believers of all ages, including ourselves.