E. The Kings and Governors of Palestine

As stated in the first article, Rome was not fortunate in her choice of those by whom the Jewish nation was ruled. This was not wholly the fault of the emperor since, in a world where men lust to make quick fortunes and exploit all the resources of bribery and extortion to fulfill their aims, the choice of men of honesty and good judgement is limited. The Emperor Tiberius appears to have recognized this problem since he allowed his provincial governors to continue in office for longer periods than his predecessor Augustus. When asked why he followed this policy, he is said to have justified it by the fable of the wounded man who lay by the roadside covered with blood-sucking insects. A compassionate passer-by who began to brush them off was begged to desist. “These flies”, said the wounded man, “are already sated with blood and are causing me no trouble now; but if they are driven off a fresh swarm of hungry ones will take their place, and I shall not survive their attentions”.1 [Note]\[Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 18, Chapter 6.5.] The rapacity of many provincial governors is only too well attested in Roman records.

Herod the Great

Of Herod the Great it can be said that it is a remarkable tribute to his charm, daring, political acumen and consummate diplomacy that he won praise from both the triumvirs Octavian and Antony, who were so” soon to divide in disastrous rivalry. The whole remarkable story is told in Josephus.2 [Note]\[Wars of the Jews, Book; Antiquities, 17.7.] Two years of tireless activity made him the master of his inheritance (his father Anticipate was procurator of Judea). “Caesar [Octavian] replied to him thus: ‘Nay thou shalt not only be in safety, but shalt be a king and that more firmly than thou wast before for thou art worthy to reign over a great many subjects, by reason of the fastness of thy friendship’ “.[Note]\[Wars,1.20.2.]

Herod was a ruthless fighter, but at the same time a cunning negotiator. A subtle diplomat and an opportunist, he was able to restrain his Roman helpers and simultaneously circumvent the Jews. To manage a situation so complex and to survive demanded uncommon ability and an ordered realm. Of his ability there is no doubt, and, indeed, he gave Palestine order, and opportunity for economic progress.

But there was a dark side to him. He was a cruel and implacable tyrant. His family and private life (he married nine or ten wives) were soiled and embittered by feuds, intrigues and murder. Only five days before his death he ordered his son Antipater to be slain, and shut up “all the principal men of the entire nation”, ordering that they should all be killed after his death (which was expected soon), that it might afford “the honour of a memorable mourning at his funeral”. The order was never carried out.’ It is thus easy to understand how it is in accord with his character that the enquiry made by the Wise Men, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews?”, should so arouse his jealous spirit that he “sent forth, and slew all the children that were in Bethlehem” (Mt. 2:2,16).

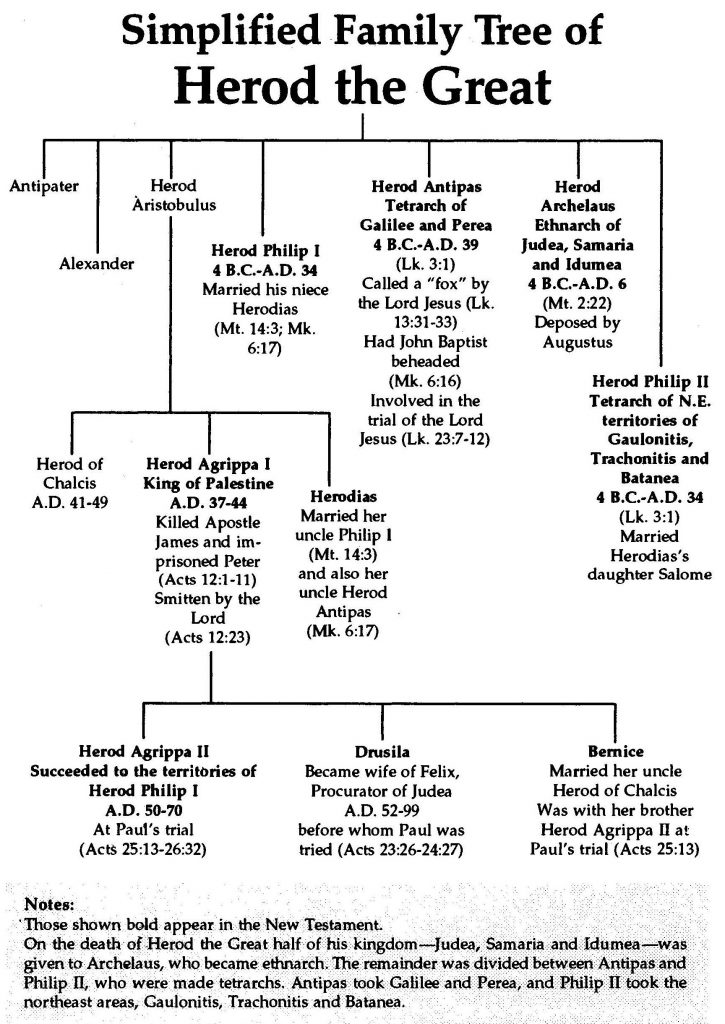

In the simplified chart of Herod’s family the names of those specifically mentioned in the New Testament are accompanied by the Scripture references.

Herod’s will divided the kingdom; Archelaus took Judea and Idumea, by far the choicest share. He inherited his father’s vices without his ability, took the title king (Augustus refused him royalty and made him ethnarch), and bloodily quelled the disorders that broke out in Jerusalem. The result was widespread disorder which required the intervention of Varus, legate of Syria. It was at this time that Joseph and Mary returned from Egypt with the young Lord Jesus: “But when he heard that Archelaus did reign in Judwa in the room of his father Herod, he was afraid to go thither” (Mt. 2:22). Archelaus maintained his stupid and tyrannical reign for ten years, but in A.D. 6 a Jewish embassy finally secured his deposition and banishment to Gaul.

Roman governors

Coponius, a Roman knight, was appointed to rule as governor. As indicated in the previous article, a tax census was the first administrative necessity, and this precipitated the revolt of Judas of Gamala and the emergence of the Zealots as a sinister force in Jewish politics.

In addition to other prerogatives held by Archelaus, and by Herod before him, Coponius took over the custody of the high priest’s vestments, which were kept in the Antonia Fortress, the headquarters of the Roman Garrison in Jerusalem. The high priest was allowed to take them out seven days before the Day of Atonement and the great pilgrimage festivals so that they might be ceremonially purified before being worn for these sacred occasions.

In A.D. 36 Lucius Vitellius, legate of Syria, as a conciliatory gesture to the Jews, obtained permission from the Emperor Tiberius to restore the custody of the vestments to the temple authorities.1 This privilege was confirmed to the Jews by the Emperor Claudius after the death of Herod Agrippa I in A.D. 44 when the procurator Cuspius Fadus (see below) tried to have them deposited as before in the Antonia Fortress under his control.2

Coponius was replaced about A.D. 9 by Marcus Ambivius, and he made way about three years later for Annius Rufus, who. was in office when Augustus died (19 August A.D. 14). About A.D. 15 Tiberius sent Valerius Gratus to govern Judea, and he held office for eleven years. Since the king or governor had yet another prerogative, that of appointing the high priests, he deposed four and appointed another four, perhaps his own particular way of enriching himself.

The last high priest he appointed was Joseph Caiaphas, son-in-law of Annas, the latter being in office when Gratus arrived in Judea.

The governorship of Pontius Pilate

Gratus was succeeded by Pontius Pilate, the only one of the earlier prefects of whom we have detailed information owing to the part he plays in the New Testament and the account of his governorship given by Josephus. In addition there is a description of his character and conduct in a letter written by Herod Agrippa I to the Emperor Caligula in A.D. 40. In it he is described as “naturally inflexible, a blend of self will and relentlessness”?3

It is an interesting fact that Pilate’s patron appears to have been the evil genius Sejanus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard and, in the years immediately preceding his downfall, the most powerful man in Rome. His ascendancy even over the Emperor Tiberius was at its height in the early years of Pilate’s governorship, and the fact that he was bitterly anti-Jewish could well explain Pilate’s provocatively inflexible attitude to the Jews. Had Sejanus remained in power but a few years longer this might well have radically altered Pilate’s approach to the trial of the Lord Jesus Christ. But Sejanus fell from power in A.D. 31, and this changed situation would have made Pilate particularly sensitive to the chief priests’ scarcely veiled menace at the trial of the Lord Jesus: “If thou let this man go, thou art not Caesar’s friend” (Jno. 19:12).

Another matter of interest (already referred to in Part 1) is that of Pilate raiding the temple treasury to obtain money for the construction of an aqueduct to augment the city’s water supply.4 Crowds of indignant Jews gathered in protest against this sacrilege, but their demonstration was forcibly broken up. It has been suggested that this may well have been the setting of the incident in Luke 13:1, when Pilate’s troops attacked a number of Galilean pilgrims in the temple court so that their blood was mixed with the blood of their sacrifices. In any case, the incident illustrates the unrest of the period and the insensitive attitude of Pilate. The Galileans were not Pilate’s subjects although they were temporarily under his jurisdiction when they visited Jerusalem. But his attack on them probably contributed to the personal hostility between Pilate and Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee, whose subjects they were, which Luke refers to in 23:12.

Immediately after referring to the incident of the Galilean pilgrims, Luke mentions the death of eighteen men when a tower in Siloam (in the southeast corner of Jerusalem) fell and crushed them. This may have been a tragic accident, but the context in which it appears suggests that it relates to an attempt at insurrection around this time by a group of militants, who were crushed in the fall of a tower when the Romans undermined it.

Pilate was finally despatched to Rome to give an account of his actions to the emperor by Lucius Vitellius, legate of Syria, who then appointed one of his lieutenants, Marcellus, acting procurator. Pilate set out for Rome without delay, but by the time he reached the capital Tiberius was dead. Pilate was not confirmed in office by the new Emperor Caligula; a new man Marullus was appointed, and he retained his office throughout Caligula’s reign. He was followed, not by another Roman governor, but by a Jewish king, Herod Agrippa I.

The rule of Herod Agrippa I

It was an act of great political wisdom on the part of the incoming Emperor Claudius to appoint Herod Agrippa as king of the Jews, for, unlike his grandfather Herod, he was accepted by the Jews as one of them because of the fact that he was a Hasmonean through his grandmother Mariamne, who was in turn granddaughter of the former high priest Hyrcanus II. He in turn was the great-grandson of Simon, brother of Judas the Maccabee.

Outside the purely Jewish areas of his kingdom he was no more restrained by Jewish religious scruples than his grandfather had been. However, he had rendered great service to the Jewish people in that he had dissuaded the unbalanced Caligula from his plan to erect an image of himself in the temple at Jerusalem, and thus avoided much bloodshed; for Petronius, legate of Syria at that time, had been assured by a deputation of the Jews that the whole Jewish nation would rise as one man and die as one man sooner than allow the temple to be desecrated by the Imperial statue.5

Agrippa came into conflict with the legate, Vibius Marsus, who replaced Petronius. One of the occasions concerned the Third Wall which Agrippa began to build to the north of Jerusalem so as to enclose the suburb of Bezetha north of the temple area. Marsus suspected that the strength and height of the wall were such as to encourage excessive feelings of independence among the people of Jerusalem, and he sent instructions to Agrippa to carry it no further.°6

Agrippa is the Herod of Acts 12 who executed James the brother of John and imprisoned Peter, and who, “upon a set day”, probably Claudius’s birthday celebrations, “made an oration” (v. 21). Josephus describes how the king took his seat in the theatre at daybreak, wearing a robe woven with silver thread, which reflected the rays of the rising sun so that the people invoked him as a god. Luke says that he made a speech from his throne which was greeted with the shout, “It is the voice of a god, and not of a man” (v. 22). Both writers agree that it was at that moment that he was seized by mortal pain, and indicate that this was because he did not repudiate the divine honours accorded him by the crowd. He was carried home and died five days later.

Back to governors

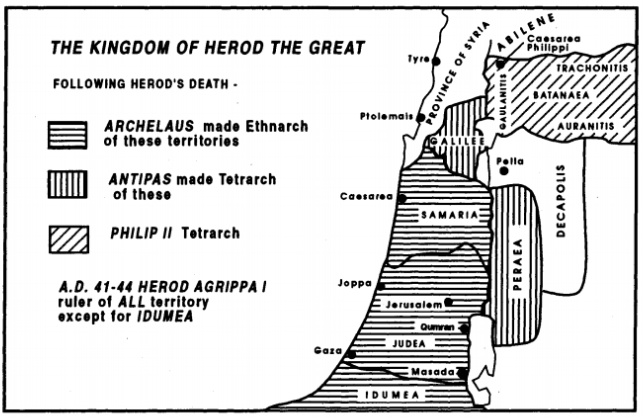

Agrippa’s death at the age of fifty-four was a tragedy for Judea. Had he lived as long as his grandfather the disasters of the following decades might well have been averted (I write after the manner of men—God rules in the kingdom of men!). His seventeen-year-old son Herod Agrippa II (the Agrippa of Acts 25:13—see chart) was refused his father’s kingdom on the grounds that he was too young to be entrusted with so difficult a realm as Judea. But subsequent events show that he could hardly have done a worse job than the procurators who were appointed. Cuspias Fadus, the first procurator to be appointed, took over all Agrippa’s kingdom, which was practically co-extensive with that of his grandfather, Herod the Great (see map), and thus Galilee became part of the province of Judea.

Fadus was followed by Tiberius Julius Alexander, member of a most illustrious Jewish Egyptian Alexandrian family and nephew of the philosopher Philo.7 However, his appointment was not acceptable to the Jews since Alexander was an apostate from Judaism and let this be known. When he arrived in Judea the province was suffering from the famine predicted by Agabus (Acts 11:28).

Another noteworthy event of his procurator-ship was his crucifixion of Jacob and Simon, two sons of Judas the Galilean, the originator of the Zealot party which Josephus refers to as the “Fourth Philosophy” and to which he traces all the ills which befell the Jews of Palestine in the following decades, culminating in the devastation of the land and the burning of the temple.”[Note]\[ Antiquities, 18.1.1.] Though he does not say so in so many words, it would appear that the “Fourth Philosophy” is identical with the Zealots, the other ‘philosophies’ being the parties of the Pharisees, Sadducees and Essenes.

Although we have no details of the ‘crimes’ of Jacob and Simon it is interesting to note that from A.D. 44 there was an increase in militant messianism. During the governorship of Fadus, one Theudas arose (not the one of Acts 5:36, who was much earlier), and in the governorship of Felix (52-60) there arose the Egyptian (Acts 21:38) who marched on Jerusalem. A movement similar to those led by Theudas and the Egyptian is recorded in the procuratorship of Festus (60-62).” 8Thus the tide of insurrection against Rome was growing.

Felix and Festus

The procuratorship of Ventidius Cummanus was punctuated by a succession of clashes which led to his deposition and banishment, and he was succeeded by Felix, a man well known to us because of his contact with the Apostle Paul. Although he was a freedman (made so by Claudius) he so impressed his superiors and the Jews alike that he was made procurator, an unheard-of promotion. However, the Jews, who had so welcomed his appointment, soon had reason to change their minds.

Felix makes a more sympathetic appearance in the New Testament (Acts 23:24-25:14) than he does elsewhere in ancient literature. Tacitus said of him that “he revelled in cruelty and lust, and wielded the power of a king with the mind of a slave”.” 9

Unrest increased under his rule, and he was merciless in crushing opposition. “Of the bandits whom he crucified”, says Josephus, “and of the common people who were convicted of association with them and likewise punished the number was incalculable”.10 He was susceptible to flattery, as the speech of Tertullus shows (Acts 24:2-8), and also to conviction of sin, as is demonstrated when Paul reasoned before him about “righteousness, temperance, and judgment to come” (Acts 24:25). However, his conviction faded, he procrastinated, and held Paul about two years, hoping the apostle would offer him a bribe for his freedom (v. 26).

He was replaced by Porcius Festus, of whom almost nothing is known before his appointment by Nero. He appears in Acts (24:27-26:32) principally in his relationship with the Apostle Paul. Festus was apparently a far better man than Felix, and more efficient. At the beginning of his governorship he took up Paul’s case and agreed with King Agrippa (Herod Agrippa II of Chalcis) that he could have been set free had he not appealed to Caesar. However, while he tried the apostle’s case with commendable alacrity (Acts 25:6), and was convinced of his innocence (26:31), he was prepared to sacrifice Paul to do the Jews a pleasure (25:9), hence the scandalous suggestion of a retrial in Jerusalem. Paul was constrained to appeal to Caesar in the face of an arrangement which would have put him in the power of his enemies.

If Paul was now bound by his appeal, so likewise was Festus. Augustus had enacted the law Lex lulia de ui publica a few years after 30 B.C., which forbade any magistrate to kill, scourge, put in chains, torture or even sentence a Roman citizen who had appealed to Caesar, or to prevent him from going to Rome to lodge his appeal within a fixed time. Thus Paul was completely protected from his enemies. Apparently also the provincial judge was obliged to send to Rome an explanatory statement of the case along with the accused man. Festus was thus glad to have help from Herod Agrippa II in this case.

As an aside, F. F. Bruce suggests a deeper reason for Paul’s appeal, since from what we know of him his own safety was not the consideration always uppermost in his mind. Seven or eight ‘years earlier Paul had experienced the benevolent neutrality of Roman law in the decision of Gallio at Corinth (Acts 18:14-17). Gallio had ruled in effect that what was preached was a variety of Judaism and therefore not forbidden by Roman law. Thus the gospel could be preached without interference. But, thanks largely to Paul’s own activity, Christianity was becoming more Gentile than Jewish. In these circumstances a Gentile monarch might well be more favourably inclined than the Jewish authorities, and this being so he might win for the faith the right to be treated as a religion in its own right. F. F. Bruce concludes: “It would be precarious to set limits to Paul’s high hopes, however improbable they may appear in retrospect to us, who know more about Nero than Paul knew in A.D. 59”.11

After Festus

Festus died in office in A.D. 62, and three months elapsed before his successor Lucceius Albinus arrived. It was during this interval that James the Just and certain others were stoned to death in Jerusalem by sentence of a court illegally convened by the high priest Annas (Ananus) II. Josephus gives no hint of the nature of their alleged crimes but makes it plain that the high priest offended a lot of fair-minded people. Not only was this the case, but when the news of the stoning reached the new procurator he wrote an angry letter threatening to punish Annas and his associates for taking upon themselves the right of capital punishment which belonged to the procurator alone. To conciliate Albinus, Herod Agrippa II removed Annas from office.

Towards the end of the procuratorship of Albinus the restoration work on the temple, begun by Herod the Great over eighty years earlier, was completed. This threatened a large number of workmen (Josephus says “above eighteen thousand”17)[Note]\[Antiquities, 20.99.7.] with sudden unemployment, an undesirable situation in the prevailing unrest. Therefore, to provide new jobs, the authorities urged Herod Agrippa II to raise the height of the eastern colonnade, Solomon’s Portico, which overlooked the Kidron Valley. Agrippa refused to finance this operation, but agreed to pave the city with white marble. A year or two later, however, when the temple foundations showed signs of sinking, at great expense Agrippa imported wood from Lebanon to underpin them. The work was interrupted by the revolt against Rome which broke out in September A.D. 66, and the remainder of the wood was used for the defence of the temple area four years later when it was besieged by Titus.

Albinus was succeeded by Gessius Florus, who is said to have owed his appointment to his wife’s friendship with Poppaea Sabina, wife of the Emperor Nero. Josephus has nothing good to say about Albinus, but admits that, when they began to experience his successors’ mismanagement, the Jews looked back on Albinus as a public benefactor.”12 Florus’s lust for wealth was such that the resources of bribery and extortion were exploited to gratify it. Breaking point came when he raided the temple treasury and seized seventeen talents, claiming that they were required for the Imperial service. His action, sacrilegious in Jewish eyes, provoked a riotous demonstration which he treated as rebellion. He seized a number of leading citizens indiscriminately and crucified them, and handed over part of the city to his troops to plunder. It was thus under Gessius Florus that the revolt against Rome took place. His misrule provided the immediate causation for it.

- Antiquities, 18.2.3.

- Antiquities, 20.1.1.

- Antiquities, 18.3; 18.4.1; Wars, 2.99; Philo, Legatio,3.1.

- Wars, 2.9.4; Antiquities, 18.3.2

- Antiquities,18.8; Wars, 2.10.

- Antiquites, 19.7.2.

- Judaeus Philo (?20 B.C. – A.D. 54) was a Jewish philosopher, born in Alexandria, who sought to reconcile Judaism with Greek philosophy.

- Antiquities, 20,8.10.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus (?A.D. 55- ?A.D. 120) was a Roman historian and orator. His works include Annals, dealing with the period A.D. 14-68, and Histories, dealing with the period A.D. 68-96. The quotation is from Histories, 9.

- Wars, 2.13.2.

- New Testament History, Pickering and Inglis, Basingstoke, 1985.

- Wars,2.14.2.