The High Priests

Until the crisis precipitated by Antiochus IV, eighth king of the Seleucid dynasty (175-163 B.C.),1 and the kings immediately responsible for the outbreak of the Maccabean wars, the high priesthood had for many centuries been restricted to the house of Zadok.2 This house provided the chief priests in Solomon’s temple from its foundation until its destruction by the Babylonians in 587 B.C., and in the post-exilic temple onwards.

The last legitimate high priest of the house of Zadok to hold office was Onias III, who was deposed about 174 B.C. and assassinated three years later. He was replaced by his brother Jason, who promised to promote the king’s policy of bringing Greek thought and ways into the life of the Jewish people. He was deposed in 171 B.C. and replaced by Menelaus, who was not of Zadokite stock, and perhaps not of a priestly family. When he fell from favour Alcimus was appointed (161 B.C.) and, though not of Zadok, was recognised as a priest of Aaron’s line.

About this time Onias IV, son of Onias III, seeing there was no hope of a restoration of the legitimate high priesthood of Zadok, took himself off to Egypt, where Ptolemy VI allowed him to found a temple at Leontopolis, on the model of the Jerusalem temple. There he and his descendants maintained a succession of priests for 230 years, until their temple was closed by the Emperor Vespasian soon after the fall of Jerusalem in A.D. 70.

The Hasmonean line

Meanwhile, the high priesthood in Jerusalem fell into the hands of the Hasmoneans, to whom Judas the Maccabee and his brothers belonged. Their house was a priestly family of the order of Jehoiarib.3 When Simon, brother of Judas, succeeded as leader of the Jews a popular assembly in September 140 B.C. decreed that he be appointed ethnarch, commander-in-chief and hereditary high priest, “high priest for ever”4 as the decree phrased it. From Simon until the downfall of the Hasmoneans the high priesthood remained in that family, and was usually co-joined with the civil ruler ship. The Pharisees tolerated this situation under protest, but the community of Qumran found the situation so intolerable that they withdrew from association with a temple defiled by an illegitimate priesthood and maintained a theoretical loyalty to Zadok in their wilderness retreat by the Dead Sea.

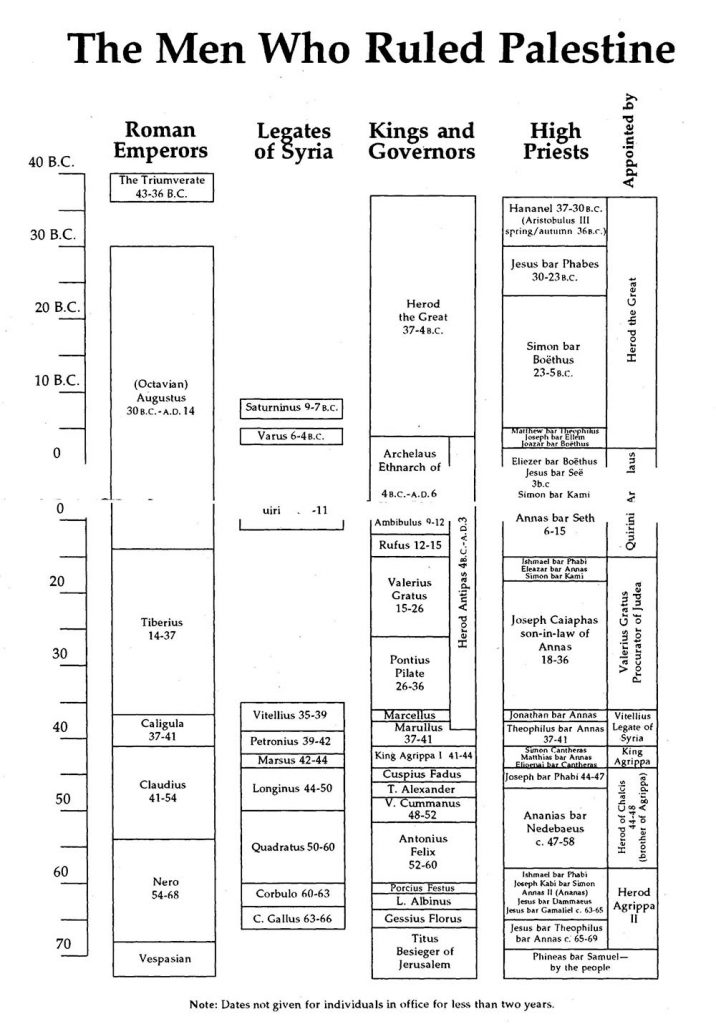

Herod the Great married Mariamne, in whom the line of the Hasmoneans came to an end and, by her marriage, passed into the Idumean line of the Herodians. From this time on, the high priests (no fewer than twenty-eight from the reign of Herod to the destruction of the temple by Titus, a period of 127 years) were deposed or appointed by Herodian kings or Roman procurators. Some of the latter, if not all, enriched themselves by these appointments.

Thus the high priests of New Testament times were not of the succession of Zadok (they were in Egypt). They were men of wealth, political opportunists. In fact, wealthy families, which provided most of the high priests from Simon son of Boethus (23-5 B.C.) to A.D. 70, also provided the captains of the temple (having charge of the temple guard) and the temple treasurers. This resulted in a concentration of power in the hands of a few rich and influential families. A snippet preserved in the Talmud expresses the attitude of the man in the street to this situation:

“For they are the high priests; their sons are the treasurers; their sons-in-law are temple-officers; and their servants beat the people with cudgels”.5

First-century priests

The first name in the chart which attracts our attention is Annas the son of Seth, appointed by Quirinius in A.D. 6. He became the head of one of the most influential high priestly families in the closing decades of the Second Temple. Five of his sons, Eleazar (A.D. 16-17), Jonathan (36-7), Theophilus (37-41), Matthias (42-3) and Annas II (61-2), one grandson, Matthias, son of Theophilus (65-8), and a son-in-law, Joseph Caiaphas (1836), became high priests. He himself ‘ retained the priesthood from A.D. 6 to A.D. 15, when he was deposed by the procurator Valerius Gratus in favour of Ishmael, son of Phabi, who, in a second period of office (58-60), apparently was the last high priest to slay the red heifer as required by Numbers 19:1-7.

Not withstanding his deposition, Annas remained the power behind the throne for many years after, playing a leading part in the preparations for arraigning the Lord Jesus Christ before Pilate (Jno. 18:13,24). Luke also ascribes to him a leading part in the early attempts by the Jewish authorities to repress the preaching of the apostles in Jerusalem (Acts 4:6).

Between Annas and Caiaphas three high priests held office in as many years, one of them being Eleazar son of Annas. But on conferring the office on Caiaphas in A.D. 18 Valerius Gratus left him as high priest for eight years, and his position was confirmed by Pontius Pilate when he arrived in A.D. 26. Thus Caiaphas and Pilate held their respective offices concurrently for ten years, and were deposed within a month or two of each other. That Caiaphas held the high priesthood for the considerable period of eighteen years may have been due in part to his personal diplomacy, and also to his wealthy connections. It would appear that no rival could outbid him as long as Gratus and Pilate governed Judea.

He was deposed by Vitellius, legate of Syria, and replaced by Jonathan, another son of Annas. He appears to have had some sense of the holiness of the office and his unworthiness because, when he was offered a second period by Herod Agrippa I, he declined, saying that it was sufficient for him to have worn the sacred vestments once.6 Jonathan was succeeded by Theophilus son of Annas. He was the high priest of Acts 9:1 from whom Saul received the “letters to Damascus to the synagogues”. Some six years after him there was appointed another high priest with whom the apostle had to do, namely Ananias son of Nedebaeus (A.D. 47-58). He was rebuked by Paul as a “whited wall” (Acts 23:3). Tradition tells us of his rapacious conduct in seizing for himself the sacrifices which ought to have gone to the other priests. This scandalous behavior was ridiculed in a parody of Psalm 24:

“Lift up your heads, ye gates, that Yohanan ben Narbi, Panqai’s7disciples.may enter,and fill his belly with heaven’s holy things!”.

Ananias lived for eight years after being deposed, and was killed by the Zealots at the beginning of the war in September 66.

The final priests

Six priests were appointed by Agrippa H in the remaining years of the Jewish dispensation. The first of these was Ishmael son of Phabi, another rapacious individual like Ananias. Josephus writes of sedition between the high priests and the principal men of Jerusalem, which disorders “were [done] after a licentious manner in the city, as if it had no government over it”.8 But the most notable of Agrippa’s appointments was the son of Annas, who bore his father’s name. This younger Annas (Aztanus) was, as we have already seen, the high priest who exceeded his authority to execute James the Just. He died at the hands of the Zealots in early A.D. 68, and his body, along with that of another high priest, Jesus the son of Gamaliel, lay exposed in the streets of Jerusalem.’ 9

The last high priest to hold office before the temple was destroyed was a priest of peasant stock, Phineas son of Samuel, who was appointed by lot.[Note]Wars, 4.3.6-8.[/note] Josephus rages against this, but so do all wealthy people who see those whom they regard as underlings elevated into the positions they regard as theirs by right. His appointment was by no means more unworthy than those made in the century that had passed away!

- 1Macc. 1:10;6:16.

- See 2 sam. 8:17;1 Chron. 15:11;2 Sam. 15;24;17:15; 1 Kgs. 1:8,44,45;2:35.

- See 1 Chronicles 24:7, where the course of Jehoiarib is the first of twenty-four.

- 1Macc.14;41.

- Babylonian Talmud, Pesharim 579.

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book 19, chapter 6.4.

- Phinehas the reprobate son of Eli; 1 Samuel 2:13-17

- Antiquities, 20.8.8.

- Wars of the Jews,4.5.2.