C. The Emperors

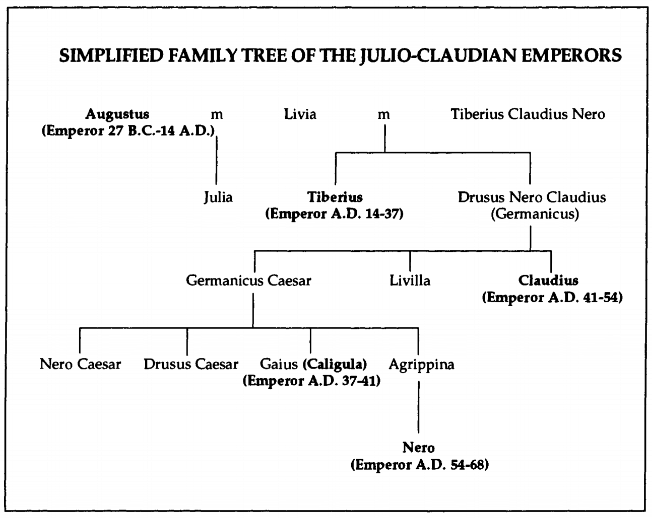

In 63 B.C. Palestine was added to the rapidly expanding Roman Empire by the Roman general Pompey. However, for numerous complex reasons Rome endured civil war for much of the first century B.C. Julius Caesar, who had conquered Gaul, fought successfully with Pompey for the supremacy and made himself dictator. When he was assassinated in 44 B.C., Brutus, Cassius and others responsible were executed by Mark Antony and Octavian (Julius Caesar Octavianus, born 63 B.C.), who subsequently fought each other for control of the empire. Octavian won at the battle of Actium in 31 B.C., added Egypt to the territory he controlled, and terminated the republic and instituted the empire. He was saluted Imperator by the senate, who conferred on him the title Augustus in 27 B.C. He ruled until A.D. 14, and was the first of the Julio-Claudian line, which lasted till A.D. 68.

The Lord Jesus was born during the reign of Augustus, and the New Testament era was inaugurated (Lk. 2:1). Under his successor Tiberius (A.D. 14-37) occurred the ministries of John the Baptist (Lk. 3:1) and the Lord Jesus, and he was the Caesar in question in the incidents of the tribute money (Mt. 22:17-21) and the veiled threat from the Jewish leaders to Pontius Pilate: “If thou let this man go, thou art not Caesar’s friend” (Jno. 19:12).

The Lord Jesus was born during the reign of Augustus, and the New Testament era was inaugurated (Lk. 2:1). Under his successor Tiberius (A.D. 14-37) occurred the ministries of John the Baptist (Lk. 3:1) and the Lord Jesus, and he was the Caesar in question in the incidents of the tribute money (Mt. 22:17-21) and the veiled threat from the Jewish leaders to Pontius Pilate: “If thou let this man go, thou art not Caesar’s friend” (Jno. 19:12).

Tiberius was followed by Caligula (Gaius) (37-41), who is not specifically mentioned in the New Testament. However, we learn from contemporary historians such as Josephus that his instructions to Publius Petronius, legate of Syria (39-42) to set up a gigantic statue of himself in the Jerusalem temple caused great concern to both Jewish and Christian communities in the city. Only through the timely intervention of Herod Agrippa I was the order rescinded and much bloodshed avoided.

Gaius was succeeded by Claudius, fourth Roman emperor (41-54) and nephew of Tiberius. A weak, vacillating man, he was poisoned by his second wife Agrippina in A.D. 54. Herod Agrippa I had assisted him much in his advancement to the rulership, and in consequence was given the whole of Palestine. Claudius also gave the Jews throughout the empire the right of religious worship, but later he banished all Jews from Rome (Acts 18:2). During the reign of Claudius Britain was conquered and Paul conducted his great missionary campaigns. The famine foretold by Agabus occurred in the reign of Claudius (Acts 11:28).

Under Nero (54-68) Rome was burned, the Christians were persecuted and Paul was put to death. The son of a distinguished family of the old Roman aristocracy, the Domitii, and on his mother’s side the great-great-grandson of Augustus, he was adopted by Claudius as his heir, and duly took his place in the Caesarian succession in A.D. 54. His atrocities and feebleness finally destroyed the credit of his house, whose long ascendancy he finally brought to an end with his suicide in the face of the revolts of A.D. 68. While not specifically mentioned by name, he was the Caesar of Acts 25:11 and the Augustus of Acts 25:25.

In this connection two interesting terms for Roman royalty are used in Acts 25. The first is sebastos, meaning ‘revered’ or ‘august’, and is used in the New Testament only in Acts 25:21,25 and 27:1. The other term is ;kyrics, meaning ‘lord’, and is used of the emperor in Acts 25:26. Both Augustus and Tiberius refused this title for themselves because they felt it exalted them too highly, and implied a relationship of master and slave. But, by the time of Paul’s appeal to Caesar, Nero was ruler, and ‘lord’ was much more commonly used of the Caesar.

When Nero did accept the title ‘lord’ he had not yet gone to the excesses that characterised his later reign. At this juncture Nero was reputed to have been a fair-minded ruler. Luke’s accuracy should be noted in his use of these titles.

The death of Nero, by now infamous, inaugurated another power struggle. The final result was that Vespasian, who had taken charge of the Roman armies following the destruction of the forces of Cestius Gallus, was proclaimed emperor, and he began the Flavian line. Three Flavian emperors ruled: Vespasian (69-79), during whose reign Jerusalem was destroyed in A.D. 70; and his two sons, Titus (79-81), the destroyer of Jerusalem, and Domitian (81-96). Under Domitian, who had a predilection for being styled Dominus et Deus Noster, meaning ‘Our Lord and God’ (a title which would have been regarded as plain blasphemy by the disciples of the Lord Jesus), persecution of the brethren and sisters took place, and the Apostle John was exiled to Patmos.

D. The Legates Of Syria

The usual fate of a country conquered by Rome was to become a subject province governed directly from Rome by officers sent out for that purpose. Sometimes, however, petty sovereigns were left in power (for example, Herod the Great). Judea knew both states as, when Archelaus was deposed and banished by Augustus in A.D. 6, it became a Roman province.

The governor of a minor province such as Judea was regularly drawn from the equestrian order, the second order in Roman society, whilst governors of larger and more important provinces were drawn from the senatorial order, which was the first. The troops which a governor of a minor province had under his control were auxiliary cohorts, not legionary troops. In an emergency beyond the capacity of these forces legionary troops could be provided by the legate of Syria, who appears to have exercised some control over the prefect of Judea. This supervision was called for only when the prefect of Judea was involved in serious trouble with the people of the province, as happened with Pilate (A.D. 36), Cumanus (A.D. 52) and, above all, Florus, under whom the Jews revolted against Rome (A.D. 66).

The legate of Syria at the time of the deposition of Archelaus was Publius Sulpicius Quirinius (the Cyrenius of Luke 2:1). He had the task of liquidating the estate of Archelaus and holding a census to determine the amount of tribute which the new province of Judea might be expected to pay into the imperial exchequer.1 It was this census that provoked the rising under Judas the Galilean, and gave birth to the Zealot movement.

Some have raised problems about the references to Quirinius in Luke 2:2,2 but there is in fact no problem. As indicated above, Quirinius was sent to liquidate the estate of Archelaus. Now that Archaelaus’ ethnarchy had become a Roman province a census was held to determine taxable income. A record was also required of those liable to pay tax, hence the census; but it was an earlier, ad hoc census, not one of the regular censuses, to which Luke is referring in Luke 2:2. The confusion arises out of the translation of the Greek word prate, rendered in the AV as “first” in Luke 2:2, but as “before” in John 1:15 and 15:18. Superior scholars translate as “before”, and render Luke’s statement: “This was the census that took place before Quirinius was governor of Syria”.

By the time of the appointment sixty years later of Cestius Gallus as legate of Syria (A.D. 63-6) events in Palestine were really boiling over. Disputes in Caesarea between the Jewish and Gentile inhabitants of that city are rightly reckoned by Josephus3 as being among the causes of the war against Rome which broke out in September 66. But the immediate cause of the war must be sought in Jerusalem, and the man chiefly responsible for precipitating it then was Gessius Florus, procurator of Judea in the closing years of the Jewish nation.

The Zealots who had wrested the fortress of Masada from the Romans, learning of the revolt in Jerusalem, marched on the city, no doubt thinking this to be the hour for which they had long been waiting. It may seem incredible that the insurgents should have hoped for any success in resisting the might of Rome, but the victories of Judas the Maccabee4 (‘The Hammerer’) and his brothers were only a century-and-a-half old. They too had taken the field repeatedly against overwhelmingly larger forces, and won independence for Israel. What had been done then could be done again, and indeed it might well have appeared that history was repeating itself when Cestius Gallus and his legionary forces were ambushed by the insurgents in the pass of Beth-horon where Judas ‘The Hammerer’ had won more than one victory over the larger and more heavily armed forces of the hated enemy.

This initial success of the revolt discredited the moderates and leaders of the peace party and encouraged the insurgents to organise the whole Jewish population of Palestine for the war of liberation.5

- Antiquities of the Jews, Book 17, chapter 13.5; Book 18, chapter 1.1ff.

- See, for example, entries under ‘Quirenius’ in The New Bible Dictionary and The New International Dictionary of the Bible. Also New Testament History, F. F. Bruce, p. 30, note 1.

- Antiquities, 9.9.

- Judas the Maccabee, not Judaeus Maccabeus, which is the Greek form of his name. Since he gave his life in fighting the spread of Greek culture in Judea he would have abhorred this form of his name.

- Wars, 19.8-9