An Old Favourite

In Reviewing the first edition of The Protesters in The Testimony in 1977, the late Brother Bert Salter chose to let the book speak largely for itself, by quoting liberally both from the author’s commentary and from the extensive source-material reproduced in the book. Indeed, the principal feature of The Protesters, in both its first and second editions, is the range and extent of the author’s quotations from the original materials which he has assembled through thirty years of assiduous research into the history of the Truth from the twelfth century to the present day. Brother Eyre’s great achievement, as those who have read the first edition will already know, is the expert synthesis of this vast array of materials, from different countries and from different ages, into a unified thematic history which, in the author’s own words, tells “how a number of little-known individuals, groups and religious communities strove to preserve or revive the original Christianity of apostolic times”. The author’s success in this basic objective is indicated by the popularity of his book in our community hence the publication of this second edition less than a decade after the appearance of the first. It will be the aim of this review not simply to assess the extent and value of the additional material now contained in the new edition, but also, in the process, to remind those who already knew, and to convince those who may not yet appreciate it, that The Protesters is everything that a worthwhile book should be: informative, authoritative, compulsive and uplifting

What’s new?

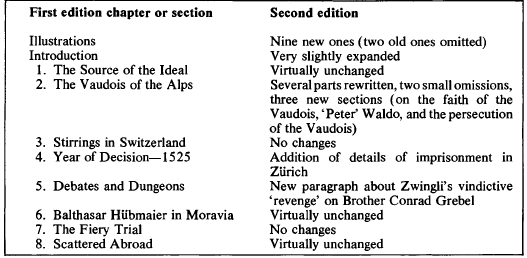

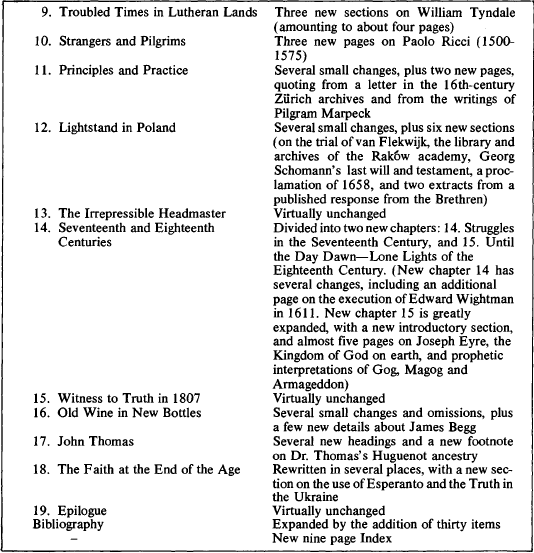

It is clear from the amount of new material in this second edition that in the years intervening between the two editions the author has kept up his research activities—a fact confirmed by his recent publication of a companion volume to The Protesters, Brethren in Christ (reviewed in The Testimony, June 1984). It has been estimated that The Protesters now contains 15 per cent more material than when it was first published; but this bald statistic gives no indication of the nature or value of the additions. It is hoped, therefore, that the following analysis, based on a careful comparison of the two editions, will give readers a clearer idea of the differences, and may help them to decide, perhaps, that they ought to obtain and read the new edition, even if they already have the first.

The effect of all these changes is to increase the usefulness of the book as a source of reference about the history of those believers who have “dared to be different” in earlier centuries. And, as Brother John Morris explains in his “Note to the 1985 Edition”, the new sections in particular “extend the history of the movements of the brethren who took the Gospel to Romania and Russia, and … expand the period between the 1660 European expulsions and the 19th century”.

Highlights of the new material

The new edition has been rendered infinitely more serviceable by the addition of an excellent index, which incorporates not only personal and place names, but also, especially helpfully, doctrinal subjects and titles of all books, pamphlets and periodicals mentioned in the text. Thus, the heading “Baptism” yields no less than twenty-seven principal page references which could well provide much basic material for use in private study or public discussion. Other major topics like “Breaking of Bread”, “Ecclesial Organisation”, “Jesus Christ”, “Kingdom of God” and “Mortality of Man” are similarly indexed with references that could be put to much good use.

That apart, the new material itself has many highlights, from which a selection will serve to whet the reader’s appetite and convey the special flavour of the book as a whole. From the expanded chapter on the Vaudois comes interesting evidence that “in general the Vaudois believed the Scriptural doctrines of the mortality of the soul and the resurrection”, a contemporary pointer to this fact being the ancient inscription which still persists at the entrance to a Vaudois cemetery in the Italian Alpine village of Torre Pellice: “The dead in Christ shall rise”. With reference to ‘Peter’ Waldo comes this ironic remark about his 12th-century burial place: “Waldo died in Bohemia. He was interred on a hilltop in southern Czechoslovakia which is still called Waldhaus, although today’s Marxist population has no idea why”.

The new material on Tyndale alone would have made this second edition worthwhile. Brother Eyre has transformed a rather sketchy few paragraphs about Tyndale in the earlier version of this chapter into a substantial explanation of Tyndale’ s persecution and execration by Romanists and early Anglicans alike. He concludes that it “now seems more than likely that Tyndale died at Vilvoorde (where he was “strangled and burnt in the prison courtyard”) not because he translated and printed the Bible—for Bibles in English were already legal by then—but because he believed and understood its truth”. In this connection, too, we are treated to a number of quotations from Tyndale’s own writings which quite clearly demonstrate Brother Eyre’s assertion that Tyndale “came to realise that not only was Roman Catholic Christendom hopelessly astray but the newly-arisen Protestant Reformers were very little better!”

The new sections in chapter 10 introduce us to the Sicilian-born 16th-century ‘heretic’ Paolo Ricci, who suffered much at the hands of the Inquisition in Italy but who escaped to the Alpine valleys and spent the rest of his life building up the communities of the Brethren there. His major ‘crimes’ were to teach that Christ bore our “sinful flesh”, inherited from Adam, that no-one will enter God’s Kingdom until after the resurrection and judgement, and that independent, personal Bible study rather than recourse to the ‘church’ is the only way for men to find the Truth. The fact that he “managed to avoid all trinitarian formulas in his correspondence” was an additional feature which did not endear him to either the papal or the Protestant authorities.

From the writings of Pilgram Marpeck (1531) comes a delightfully worded explanation of the nature of Christ as viewed by the Swiss Brethren; from Georg Schomann’s will comes a moving account of the faith and work of the Polish Brethren; and from the indictment and sentence passed on Edward Wightman at Lichfield in 1611 comes an amazingly Christadelphian’ list of’ heresies’, said to have been “by the instinct of Satan by ( Wightman) excogitated and holden”. Many interesting pages are added about the published views of a certain Joseph Eyre (no relation!) who, in 1771, set forth clearly some “very detailed expositions of Bible teaching on the Promises to the Fathers, the Hope of Israel, Christ’s return and the millennial reign of Christ on earth”. And what the 18th-century Eyre has to say about the reasons for the neglect of Bible prophecy by Christianity in general can suitably serve as a typical example of the attitude of all those whose Bible-centred lives are memorialised in this book: “When the church, by an accession of wealth and power, was so corrupted as to mind little else but enriching itself, to the neglect of scriptural studies in general, it is not strange that the study of the Prophecies should be discouraged, and almost wholly neglected. During the Papal tyranny, we have so very few, and those erroneous, explications of Scripture prophecies in general. But when the Reformation began to take place, and the sacred Scripture, which had so long been shut up from the people, was again laid open for the perusal of all Christians, the study of the prophetical parts began to revive”.

Reassuring history

It is a source of great reassurance to 20th-century ‘Protesters’ to know, in such abundant detail, that they are not alone in having “dared to be different” from the prevailing theology of their day; and the new edition of Brother Eyre’s book has brought much additional and helpful evidence about our earlier counterparts in bygone centuries. Such men and women were not “cranks, religious maniacs, fools, masochists in love with martyrdom”. Instead, it comes as a genuine comfort to know that it was their unswerving loyalty to the Word of God, their inextinguishable love of God and His Son, and the strength of their fellowship together in Christ which enabled them to ‘protest’, and helped them to form “a redemptive society that (was) as the savour of salt in a world of corruption”.

The Protesters is a really excellent book. If it is still (to some extent inevitably) sketchy in one or two places, even after all the improvements of this second edition, it is nevertheless a history book with a wholly worthwhile didactic purpose. Every modern brother and sister in Christ should find it, as the reviewer did, a real pleasure to read history written from the point of view of Bible Truth. Such books are too few and far between to be overlooked. Because it is so well researched, The Protesters is both informative and authoritative—and even more so now in this new edition. And because it concerns the life and faith of men and women like ourselves, it is compulsive reading. But, above all, because it challenges our faith with so many examples of patient endurance in tribulation, it can uplift us by spurring our consciences to greater witness to the truths which we believe. As the author writes: “If the faith of Christ means anything at all, it is worthy of our highest and our all. This, more than any other, is the basic message of this book