Introduction[1]

[1] The Lachish Letters. Unearthed in the twentieth century, the Letters form one of the most important groups of pre-exilic Hebrew inscriptions known today.[2] They add much to our knowledge of Judea at the end of the First Temple period, including both social and historical aspects.[3]

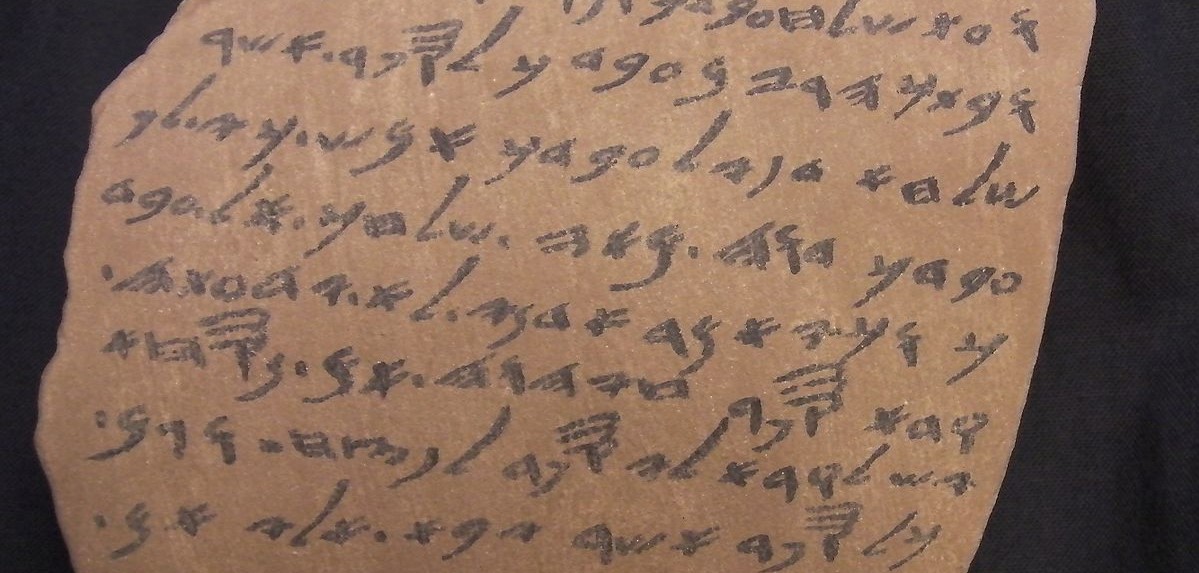

Possibly in early summer 589 BCE, prior to the Babylonian invasion of Judea (begun in January 588) by Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BCE), correspondence between two (military or administrative) officials, was penned onto potsherds (ostraca).[4] These ostraca came to light at Tell ed-Duweir, acknowledged as the site of the ancient Judean city of Lachish[5], during the British excavations led by J. L. Starkey in 1935-1938.[6] They were found in a burnt layer (Level IIC) dated to the Babylonian destruction of the city in 587/6 BCE, in or near the main gate complex at the south-west corner of the city wall.[7]

Lachish, the most important city in Judah after Jerusalem, is about 40 km (25 miles) south-west of Jerusalem. Its strategic and fortified hill-top location meant it could guard the approaches to Jerusalem from the Mediterranean coast, the Shephelah, and through the Judean hills. It was amply supplied with water and surrounded with fertile farmland. The Hebrew Bible (HB) and the Lachish Letters (LL) present a complementary picture of the end of the Judean monarchy period.

It was N. H. Tur-Sinai (formerly Torczyner), in his 1938 editio princeps, who gave the name “Lachish Letters” to the eighteen ostraca originally unearthed in 1935. Since then, the whole collection, comprising twenty-two ostraca, three added in 1938 (Tur-Sinai) and one more in 1966 (Aharoni 1968), has become commonly dubbed with this label. However, with Pardee (1982),[8] I take twelve definitely to be letters in various states of preservation. Dobbs-Allsopp (2005) also says that the label ‘Lachish Letters’ is only “appropriate” to these twelve.[9] The non-letter inscriptions range from names, lists (of rations, or goods) to indecipherable fragments.

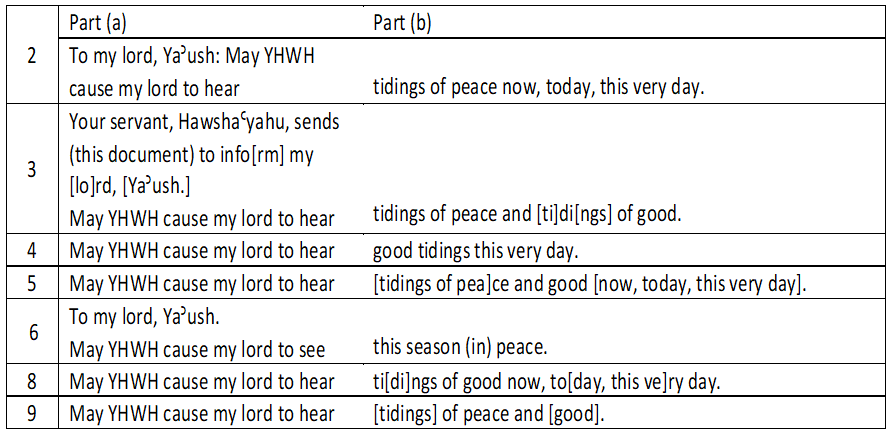

Tables [1] and [2] show why these inscriptions are (the twelve) letters. Table [3] is only to show two possible letter remnants. These tables are cited at points during this paper.

Table: [1] The address and/or the greeting praescriptio show these to be letters:

The following translations and transcriptions are adapted mainly from F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, 2005: 299-333).

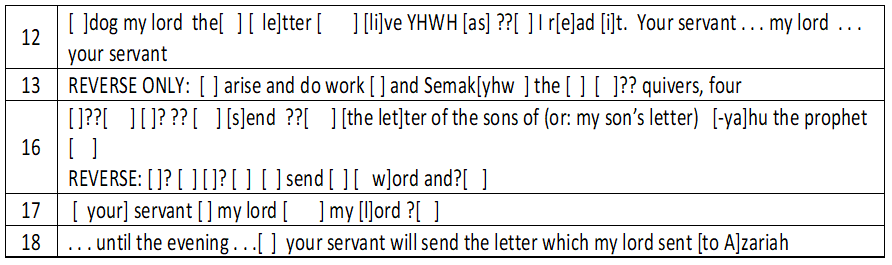

Table: [2] No preserved greeting praescriptio, but the content suggests they are letters:

Table: [3] These may each be a remnant of a letter (‘letter’ is a reconstruction):

My paper focuses on the twelve inscriptions identified above as letters, which I label, e.g., ‘LL2’ (‘Lachish Letter 2’ [or, II]). I use LO1 for non-letter ‘Lachish Ostracon 1’, etc.

Lachish Ostracon 1

(The British Museum)

All these texts, not just the letters, were written in alphabetic paleo-Hebrew script with a reed pen using black iron-carbide ink. LL3 (1.003)[10], a “practically complete ostracon, is the longest of what should probably be called a paleo-Hebrew letter from the First Temple period.”[11]

[2] Historical context. In the superpower rivalry for the Levant, Babylon was in the ascendancy over Egypt. Nebuchadnezzar’s victory over Pharaoh Necho II (610-595 BCE) at Carchemish in 605 BCE forced Egypt to abandon its imperial interests in Syro-Palestine.[12]

The Babylonian Chronicle records the seizure and first fall of Jerusalem (16 March 597 BCE), an event also recorded in 2 Kings 24:10-17, which identifies the deposed king as Jehoiakin (‘Jehoiachin’), who was exiled with the elite of Judah[13], and names Nebuchadnezzar’s nominee Zedekiah as Judah’s last king (597-587 BCE).[14]

Ussishkin has shown that Lachish was abandoned for several decades after Sennacherib’s decimation of the Level III city, conventionally dated 701 BCE.[15] Against the view that Lachish was rebuilt in Josiah’s reign, Tatum (2003) argues that this happened earlier in the closing years of Manasseh’s reign linked to a re-emergent centralisation of Judea (cf. 2 Chron 33:14).[16] It was, though, a smaller and less defensible fortified town than the Level III city.[17]

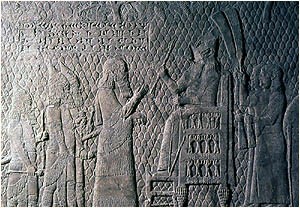

Sennacherib sits on his throne at Lachish receiving the capitulation of the city

(The British Museum)

It has been suggested that writing was beginning to have a new and important function in the later Judean, Jerusalem-centred, monarchy. Although not pursued here, some have said that it is not fortuitous that the Josianic religious reforms were predicated on a written text found in the temple (cf. 1 Kgs 22-23).[18]

However, Sennacherib’s attack on ancient Israel and his triumphant conquest of Lachish (see above, pictured on his palace walls at Nineveh)[19] set the trend of subservience to the empires of Mesopotamia that culminated with the destruction of the Jerusalem temple by Nebuchadnezzar in 587/6 BCE.

Social aspects of the Lachish Letters

The LL offer a fragmentary but unparalleled picture of the day-to-day concerns of an inferior, (a soldier?) Hawsha‛yahu[20] (Hosha‛yahu), as he corresponds, possibly from a location near Lachish, with his superior, Ya’ush (Ya’osh), perhaps Lachish’s commander[21], who has an administrative role, on the eve of the Babylonian attack.

W. G. Dever (2003), in “Social Structure in Palestine in the Iron II Period on the Eve of Destruction”, observes that there are numerous poignant passages (e.g., Isa 5:8 and Mic 2:2) in the prophets of Israel and Judah that involve “prophetic protest” against social inequality and exploitation. This, he says, is “an eloquent commentary on the social stratification that existed in Iron Age Israel”. He lists eleven indications of social classes from the HB (royalty, courtly circle, the military, nobles and landed gentry, and so on, down to slaves and outcast persons).[22]

Dever’s purpose is to advance a recent trend that addresses the secular history of ancient Israel, including the social context of the events in biblical history. He advocates that this approach should be developed in conjunction with the critical use of the HB and modern archaeological data, thus:

. . . with newer research designs oriented more toward social archaeology, the potential of archaeology can only increase.[23]

With an eye on correspondences with the Book of Jeremiah, I take the LL, as archaeological data, to make a unique contribution to this social orientation. Using the LL as evidence of Judahite literacy has social implications. (Orality, or its interface with literacy, is not discussed.) For my purposes, I do not (need to) assess the arguments about the origin and purpose of the LL (e.g., did they originate at Lachish? Are they originals or copies? Who was stationed where?).[24] Instead:

Literacy is a social issue; archaeology is well suited to address these types of social issues. . . . The changes in the social fabric of Judah are well known to archaeologists but have scarcely been recognised by text scholars . . . Obviously, literacy was concentrated in certain social strata as among bureaucrats, the military, priests, and merchants . . . Two army officers (as in Lachish 3) would not have been discussing their ability to read in Egypt or Mesopotamia. Lachish 3 is one of many pieces of evidence that literacy broadened beyond narrow scribal schools. . . . Seals, signatures, and jar inscriptions often represent the most mundane types of literacy. Letters often, though not always (e.g., Mecad „ashavyahu), indicate more advanced literacy.[25]

Letters are a form of social expression. The looseness or tightness of a social network may affect speech/writing patterns adopted by a speaker. I take ‘social’ to be about human interaction, whether interpersonal or intergroup, that is constitutive of a cohering society. The unique character of the LL is their interpersonal exchange,[26] although they have generally been referred to as ‘military correspondence’.[27] In different social contexts, ‘letter’ may also cover ‘document’ or ‘memoranda’ (e.g., as sent to Eliashib at near contemporary Arad requesting him to authorise the release of goods to the Kittim).[28]

The most obvious correlate of social status in language behaviour is in the use of particular terms of address and personal pronouns (Lyons, 1977).[29] The LL offer period-specific social-status statements, in their saturated use of ‘my lord’ and ‘your servant’, contrasted with their user’s rare use of the first person pronoun. In these respects the Arad ‘letters’ to Eliashib are different from the LL. Even on the one occasion when Eliashib is addressed as ‘my lord’,[30] the fragment contains no instance of ‘your servant’ by the sender. (No hint of an exchange of correspondence relates to their purpose.)

In this epistolary context, apart from the atypical address formula of LL3.1-4,[31] ‘your servant’ (often with an ‘epistolary perfect’[32] or ‘performative perfect’[33]) stands where the first person would be expected in socially less formal, or other forms of, communication.[34]

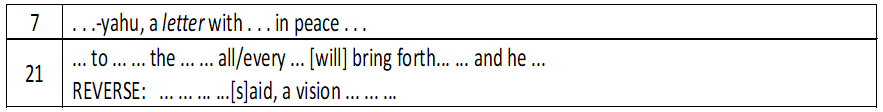

Table [4]: shows the number of deferential expressions per LL:

| Letter | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Totals |

| My lord | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | – | – | 2 | 1 | 28 |

| Your servant | 1 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 3 | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 23 |

| Totals | 5 | 13 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 51 |

Table [5]: shows the number of uses of the first person pronoun per LL:

| Letter | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 17 | 18 | Total |

|

Use of ‘I’ / ‘me’ pronoun |

1 me |

2 | 2 | – |

1 me |

– | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 7 |

Ya’ush, is first addressed in LL2 (‘in classic epistolary style’[35]), then in 3 and 6 (see Table [1], above). The sender Hawsha‛yahu[36] only has his name on LL3.[37] Unfortunately, only his ostracon-letter exchanges have survived. For now, I have assumed that all deferential references by the writer as ‘your servant’ (‛bdyk) to ‘my lord’ (’dny), as in Table [4], are Hawsha‛yahu addressing Ya´ush. I believe that, although “[t]heir content is varied . . . the letters are similar in style and tone, often using variants of the same formulas and clichés”.[38]

The social graces of the LL feature within an assumed common occupational hierarchical structure. This is not so with the two judicial letters (ca. 7th century) both recorded on ostraca to their respective ‘governor’ (hSr), one a reaper’s petition from Mecad „ashavyahu (Yavneh Yam)[39], and the other, the widow’s plea from the Moussaïeff collection.[40] Nevertheless, both observe socially-ordered deference; she with ‘your maidservant’ (´mTK) and the reaper with ‘my lord’ and ‘your servant’.[41]

With the inclusion of Hawsha‛yahu’s reactions to Ya’ush’s insinuations, which he argues are unfounded, the accident of history has preserved a unit for social analysis of two interacting pre-exilic persons. The one who is lower in the (military?) social order reacts in a manner verging on insubordination, and as in a live dramatic performance, emotional tone and personality surface. Hawsha‛yahu’s behaviour, with his self centre-staged, in LL3, fits the frame of social-psychology. One profile is:

Hosha‛yahu comes across as a blunt-speaking, professional soldier, confident in his own ability and utterly tactless in the face of authority. He is given to emotional outbursts, sarcasm, and heavy-handed irony . . . [he expresses] insubordinate criticism of royal officials in Jerusalem, possibly all the way to the king himself. . . .[42]

What is remarkable is not just that we have Hawsha‛yahu’s letters, but that we come into contact with his feelings (LL3);[43] the expressed thoughts of a socially aware Judean, possibly a military man, from the First Temple period. His use of social conventions, ‘your servant’ and ‘my lord’, mirrors cases in the HB (cf. 2 Sam 19:19-20, 26-28), as do his emotive and Yahwistic affirmational expressions,[44] which, typically, closely relate to communicational experience:

Who is your servant, a (mere) dog that my lord has remembered his [se]rvant? (LL2.3-4 [cf. LL5.3-4; 6.2-3; 12.1].

This self-abasement expression is reminiscent of 2 Kgs 8:13.

Or,

By the life of YHWH, no one has tried to read a letter to me—ever! (LL3.9-10).

This case for literacy, then, is as much a social case. The extent of literacy in late Judean society, in its social layers or institutions, has been an issue of debate in recent years. However, the LL, as texts that come to us without editorial filtering, exhibit Hawsha‛yahu’s and Ya’ush’s effective level of literate competence in social communication. Presumably, this was developed in their social background(s) or upbringing. For them this may simply mean (informal) schooling rather than schools.[45]

A contemporary incomplete Abecedary fragment found at Lachish[46] may indicate a child’s or pupil’s practice, as with an earlier “schoolboy’s exercise” found at the site.[47] Taking this and other types of inscriptional data as examples of both literacy and numeracy, A. Lemaire (1981) argued that schools existed in ancient Israel, expanding in the “early eighth century BC [implying] that by the end of the monarchy period literacy was extending to the villages and the common people”.[48] G. I. Davies (1995), considering biblical evidence, allowing for the chance finds of archaeology, and after noting the strengths and weaknesses of approaches to this matter, concludes:

[T]here is at present insufficient evidence for envisaging such a widespread educational system as that sketched by Lemaire . . . As literacy became more widespread, it may have been disseminated informally, outside of a formal school setting. But the more technical scribal skills were probably passed on, as elsewhere, through schools.[49]

Professional scribal services were on call within the social or administrative infrastructure.[50] We gather this from Ya’ush ordering Hawsha‛yahu, about which he protests (LL3.9-10), to call a scribe to read (assist his understanding of) the letter. (N.B. There is no mention of his needing a scribe to write for him. He uses a writing-tablet.)[51] Thus, on any reasonable definition of (ancient) literacy,[52] he qualifies as literate, as does his superior Ya´ush, whom Hawsha‛yahu urges to write to those causing problems in the royal court.[53] In this action, Hawsha‛yahu unintentionally provides a postal profile that brings us “within the heart of the administrative and military structure of the kingdom of Judah”.[54]

Mention is made of writers or senders of letters from the highest stratum of Judean society downwards: the king – hmlK (LL6.3-4); princes – hSrym (LL6.4); Tobijah (†Byhw), the servant of the king – `BD hmlK (LL3-4)[55], whose letter, which came to Shallum the son of Jaddua from the prophet, was subsequently sent on by Hawsha‛yahu to Ya’ush (LL3.5).[56]

Finally, even if these two LL correspondents were not literati, their scripted and read HB-matching expressions offer some contemporary indicator of other strands within Judean society who were able to engage with the sort of literary composition found in the HB.[57]

Historical aspects of the Lachish Letters

Unintended, the LL have bequeathed to us ‘insider’ angles on Judah’s last days. In this (unintentional) respect they contrast with commemorative reliefs intended for boasting of conquest, or with a monarch’s scribal chronicling of events, mundane or memorable. Nevertheless, although the manner in which information is communicated in the LL differs from the self-conscious reportage in the other kinds of texts, history is still present(ed).

I shall take historical aspects of the LL, in the Judean context immediately prior to 587 BCE, to be about events and their causal or participant actors and agencies. Regarding the contribution of the LL to historical aspects of Jeremiah’s time, Sarfatti (1982) observed that passages from the Lachish letters “could be interpolated into the Book of Jeremiah with no noticeable difference”.[58] With the social correspondences between the LL and Jeremiah, we can now emphasise historical ones.

After 587 BCE, no local king ruled in Israel until the Hasmonean period (2nd-1st century BCE).[59] Nebuchadnezzar now appointed a ‘governor’, Gedaliah the son of Ahikam, over the Judean remnant (Jer 40:11-12). Mention in the LL of the existing monarchy dates them to before the removal of the last king, Zedekiah, and the exile to Babylon.

The same can be supportively inferred from the title of the seal owner of the Shebanyahu bn/‛bd hmlk bulla (Lachish Str. II), since both titles are restricted to the monarchy period.[60] Palaeography and the archaeological destruction layer in which this bulla and the LL were found mean they cannot be dated after 587 BCE. History and historicity combine.

LO20 has an inscribed date “in the ninth (year)”, which could be that of cidqiyahu/Zedekiah (cf. Jer 39:1; Ezek 24:2), that is 589/8 BCE.[61] This can be connected to LL5 which mentions a harvest, perhaps the summer of 589 BCE. And, Ya’ush is asked whether Tobiah was going to get grain to the (still enthroned) king.

Fire-signals were a sign-system in ominous times, or had a tactical communication role (Judg 20:38-40). The term mś’t – ‘fire-signal’ – in LL4 (reverse: line 2), has contemporary usage in Jer 6:1: ‘raise a signal on Beth-hakkerem; for evil looms out of the north, and great destruction’.[62]

Jeremiah 34:7 says that only Lachish and Azekah remained of the fortified cities of Judah. LL4 (see inset ‘LL4 reverse’) ‘we cannot see Azekah’ was interpreted initially by N. H. Torczyner (1938[63]) to mean Azekah has (now) fallen; sequencing Jer 34:7 chronologically before LL4. However, recently, Z. B. Begin (2002) attempted to harmonise LL4 with Jer 34:7.[64] Azekah had not yet fallen. He argued that the writer, sending letters to his superior, Ya’ush, in Lachish[65], was based 5km north in Maresha[66] from where, it being physically impossible to see Azekah, and relying on codes given him, he says: ‘we are watching for’ (N. H. Tur-Sinai; and J. A. Emerton 2001[67]) Lachish’s signals.

This interpretation is compatible with the perspective of the LL. Movement around Judea is still possible, including going up (y‛lhw) to the capital (e.g., getting grain to the king [LL5], or Shemaiah taking Semachiah there [LL4]), and the captain of the army (Sr hcb’ ), Coniah the son of Elnathan, going down (yrd) to Egypt (LL3. Cf. Ezek 17:12-15). Jerusalem has political troubles (LL3 and LL6), but there is no hint that this is a response to Azekah having fallen.

I believe that the linguistic register of ‘we cannot see Azekah’ and co-text does not express what the concern-level, or consequences for the Lachish locality, would have been if that fort had fallen! Furthermore, nor do the Letters’ greetings (Tables [1] and [2], above), or the concern that Ya’ush might have a good harvest. If the ‘evil from the north’ had taken Azekah, just 17km north of Lachish, the LL (if then still written) would surely have quite a different atmosphere or set of referring terms.

Zedekiah’s rebellion had provoked Nebuchadnezzar’s military action; he had withheld tribute from Babylon and sided with Egypt (to whom, under Necho, Judah had formerly paid tribute). According to the HB, some of Zedekiah’s advisers and princes persuaded him to do this despite the prophet Jeremiah’s warnings (Jer 27:8-12; 37:6-8). Jeremiah, who spoke apolitically as YHWH’s prophet, was marked by the pro-Egypt party for seeming to side with the pro-Babylon faction. He proclaimed YHWH’s message that Judah should befriend Babylon since Nebuchadnezzar was (for now) YHWH’s servant (Jer 25:9; 27:6; 43:10).[68]

“The factionalism and political manoeuvring in the capital [Jerusalem] at the time”,[69] was read by Hawsha‛yahu to require damage limitation or countering. Based on letters that he had read that came from the royal court, and counting on Ya’ush’s standing, he urges Ya’ush to write to the princes causing the king problems in Jerusalem (see ‘Part of LL6’, above).

Tantalisingly, LL16.5 [-ya]hu hnb’[70] almost gives us a prophet (hnb’: ‘the prophet’) with a Yahwistic theophoric name that could connect with Jeremiah, or with Hananiah whose career of opposing Jeremiah was short-lived (Jer 28:15-17).[71] LL16.5’s ‘the prophet’ may be the one who in LL3.20 gives the warning ‘Beware!’ – hšmr – reported by Tobiah, a royal official in the palace. Hawsha‛yahu said of the princes that they were ‘weakening the hands’ (LL6). Coincidently, in Jer 38:4, the princes allege this is what Jeremiah is doing!

These linguistic and locational aspects aided the temptation to connect ‘the prophet’ to Jeremiah (yrmyhw). However, as striking as these possibilities are, D. Winton Thomas (1946)[72] shows that such data make no direct connections. Who ‘the prophet’ is remains unsolved.

Nevertheless, what is not in question is that Hawsha‛yahu (LL3), in pre-exilic Judea, considered this ‘prophet’ category to have a present occupant. This is extra-biblical historical testimony to this role.

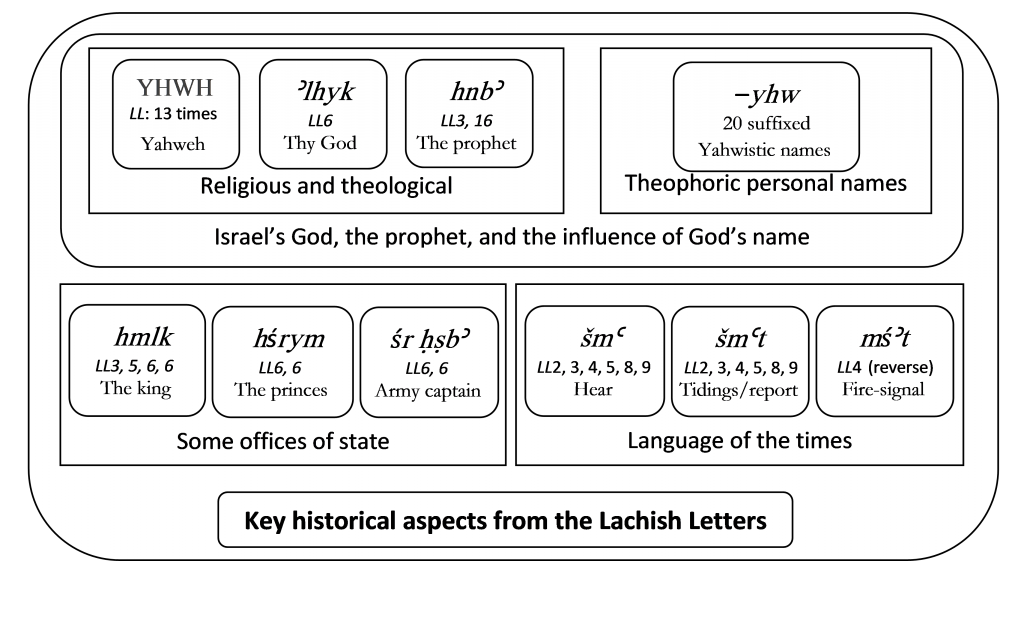

The terms from the Lachish ostraca, categorised and grouped in the diagram (below), serve as historical indicators of this late Judahite monarchy period, and in the HB some (hnb’/hnby’; –yhw names; šm‛ derivatives especially) correlate with Jeremiah’s text.

A related historical aspect that should not be missed is the Yahwistic layer (see also the diagram) in the correspondents’ language and context. (This may also affect whether Jeremiah as ‘the prophet’ is likely. He was, after all, YHWH’s prophet: Jer 1:5; 37:2.)[73]

From LL6.12-13, it is clear that Hawsha‛yahu takes YHWH to be Ya’ush’s God: ‘by the life of YHWH, your God’. Six of the seven letters (see Table [1], above) begin ‘May YHWH cause my lord to hear’, and one, LL6, has ‘. . . to see’, each followed by: ‘tidings [šm‛t] of peace and tidings [šm‛t] of good’.[74] Later in LL5, lines 7-9, he invokes: ‘May YHWH cause you to see the harvest in prosperity [lit. good], today’. Hawsha‛yahu mostly adds when: ‘now, today, this very day’. These are actual days in late, pre-exilic, Judean history, and these were live actors in them.

Hawsha‛yahu, who himself uses ‘as YHWH lives’[75], makes a connection with Ya´ush’s Yahwism. Furthermore, Hawsha‛yahu must have assumed a common viewpoint, perhaps also of piety, in his asking Ya´ush to write to Jerusalem to stop the officials who were causing problems for the king and his house.

Conclusion

In context, the onomastic evidence of twenty persons (including Hawsha‛yahu) bearing YHW-suffixed theophoric personal names, in the letters and non-letter ostraca, also permits, with the absence of any other named deity, inferences about the religion of YHWH in this last Judean generation. Though this fragment should be related to the wider picture,

The onomastics of the pre-exilic period, whether biblical or epigraphic, confirm the primacy of YHWH in the national religion.[76]

This extra-biblical picture, then, reflects (putative) historical aspects of the Jerusalem-centred First Temple religion of Yahweh presented in Jeremiah:

The primary value of the ostraca is historical in the broad sense of the term: they provide epigraphic data which in general tenor reveal a situation much like that described in the bible . . . whatever the precise relationship of these letters with Jeremiah may have been, their general contributions to our knowledge of that prophet’s time is precious enough.[77]

[1] (i) Remaining mostly unchanged, this paper was written in 2009 supervised by Robert P. Gordon FBA, Cambridge Regius Professor of Hebrew. (ii) Through contact with Professor Yossi Garfinkel at UCL in February 2014, I learnt that Lachish is his next archaeological project, following seven successful seasons at another Judean site, Khirbet Qeiyafa. However, in an email in summer 2014, he told me that his first season at Lachish was cut short by the Gaza – Israeli conflict. In that time he had uncovered an earlier entrance to the city on the northeast side of the Tel.

[2] See: http://www.tau.ac.il/humanities/archaeology/projects/proj_past_lachish.html

http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-sites-places/biblical-archaeology-sites/khirbet-qeiyafa-and-tel-lachish-excavations-explore-early-kingdom-of-judah/

[3] See op cit., n.2, p. 35.

[4] At Masada, in first century CE, there is plenty of evidence of the continued practice of writing Hebrew on potsherds for daily purposes: names, ‘rations’ or ‘coupons’, etc. Cf. A. R. Millard Writing in the Time of Jesus (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 137-139.

[5] The arguments for Tell ed-Duweir being Lachish (lkyš) are presented by D. Ussishkin (The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973 – 1994) Volumes I to V. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University, 2004): Vol. I, 50-51. On 120-121 (ibid.), R. Zadok discusses ‘The name “Lachish”’, its antiquity (occurring on a papyrus document as early as the Egyptian 18th Dynasty [LBI]), and what the name may mean.

[6] Following the first excavation under Starkey, the second was conducted in the 1960s by Y. Aharoni, and the third by D. Ussishkin from 1973-1994 (the excavation proper ended in 1987). Cf. P. J. King “Why Lachish Matters: A Major Site Gets the Publication it Deserves (The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish by D. Ussishkin)” BAR (July/Aug 2005): 36-47 (36-38).

[7] Nos. 1-15 and 18 were discovered in the ‘guardroom’ and the others nearby. All are from the same archaeologically datable stratum (IIC). Cf. Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish, 4:2099-2113.

[8] D. Pardee, Handbook of Ancient Letters: A Study Edition. Chico (California: Scholars Press, 1982), 77-114.

[9] F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp, et. al., Hebrew Inscriptions: Texts from the Biblical Period of the Monarchy with Concordance (New Haven, Conn., London: Yale University Press, 2005), 299, titles all the inscriptions as, e.g., ‘Lach 3 (Ostracon)’.

[10] G. I. Davies Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 7.

[11] Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish, 4:2102.

[12] J. Maxwell Miller and J. H. Hayes History of Ancient Israel and Judah (2nd Rev. Ed.; London: SCM Press, 2006), 460.

[13] Regarding Jehoiachin, see 2 Kings 24:6; 25:27; Jer 52:31.

[14] Cf. ‘The Babylonian Chronicle’ in T. C. Mitchell The Bible in the British Museum – Interpreting the Evidence (London: The British Museum Press, 1996), 82.

[15] See especially, Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish, Vol. IV.

[16] L. Tatum “Jerusalem in Conflict: The Evidence for the Seventh-Century B. C. E. Religious Struggle over Jerusalem” in Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period (eds. A. G. Vaughn and A. E. Killebrew; Leiden: Brill, 2003), 291-306 (304-305).

[17] P. F. Jacobs “Lachish” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible (eds. D. N. Freedman, A. C. Myers, and A. B. Beck; Grand Rapids: W. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 783.

[18] W. M. Schniedewind, “Orality and Literacy in Ancient Israel” Religious Studies Review (2000): 327-332 (328).

[19] Another Lachish Relief (in the British Museum) from Nineveh depicts the deportation of the inhabitants of Lachish and contains the first extra-biblical mention of the term ‘Judahites’. (Cf. 2 Kgs 18:13–14, 17; 19:37; 2 Chron 32:21). See A. G. Vaughn “Is Biblical Archaeology Theologically Useful Today?” in Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology (eds. A. G. Vaughn, and A. E. Killebrew; Leiden: Brill, 2003), 407-430 (425).

[20] I adopt this form as the probable pre-exilic paleo-Hebrew pronunciation from J. A. Emerton “Were the Lachish Letters Sent to or From Lachish?” PEQ (2001): 2-15 (14, n. 1).

[21] Perhaps we see the nature of the times, or a military association, in LL13: ‘. . . and Semak[yhw ] the [ ] [ ]?? quivers, four’. (Cf. ‘quiver’ – ´šPh – in Jer 5:15-16).

[22] W. G. Dever “Social Structure in Palestine in the Iron II Period on the Eve of Destruction” in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land (ed. T. E. Levy; London: Continuum, 2003), 416-431 (427-429).

[23] Ibid, 421.

[24] However, see especially Emerton “Were the Lachish Letters Sent to or From Lachish?”, 2-15, for his cogent objections to Y. Yadin, “The Lachish Letters – originals or copies and drafts?” in Recent Archaeology in the Land of Israel (eds. H. Shanks and B. Mazar; Washington and Jerusalem: Biblical Archaeology Society, 1984), 179-186.

[25] Schniedewind, “Orality and Literacy in Ancient Israel”, 330-331.

[26] Pardee, Handbook of Ancient Letters: A Study Edition, 2, offers a (broad) definition of a ‘letter’ as “a written document effecting communication between two or more persons who cannot communicate orally.”

[27] P. Bordreuil, et al., “A King’s Cammand and a Widow’s Plea: Two New Hebrew Ostraca of the Biblical Period” Near Eastern Archaeology (March 1998): 2-13 (3).

[28] Dobbs-Allsopp, Hebrew Inscriptions: Texts from the Biblical Period of the Monarchy with Concordance, 8-41, Arad 1 (Ostracon) – 18 (Ostracon).

[29] J. Lyons, Semantics (2 vols; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 2:576.

[30] 2.018.1 in Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 17.

[31] Pardee, Handbook of Ancient Letters: A Study Edition, 87, says that this is “the only formula in an official letter of the pre-Christian era which includes the sender’s name.” See LL3.1-4 in Table [1].

[32] Pardee, Handbook of Ancient Letters: A Study Edition, 35, 49.

[33] M. Rogland, “The Hebrew ‘Epistolary Perfect’ Revisited.” Zeitschrift für Althebraistik (2000): 194-200; 197-198, n. 28 (which also cites 1 Kgs 15:19; 2 Kgs 5:6), and 199, n. 38.

[34] Cf. Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 268-269, (’dny), and 451-452 (‛bdk).

[35] W. M. Schniedewind, “Sociolinguistic Reflections on the Letter of a “literate” Soldier (Lachish 3)” Zeitschrift für Althebraistik 13 (2000): 157-167 (159).

[36] Davies Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 334; and G. I. Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions Vol. 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 153, record respectively, 22 and 13 artefacts bearing this theophoric name. Most are contemporary with the LL, like the 15 bullae from nearby Tell Beit Mirsim. ‘Hosha‛yah’ (‘Hawsha‛yah’) only, occurs in Jer 42:1; 43:2. Ya’ush is only recorded at Lachish.

[37] Emerton, “Were the Lachish Letters Sent to or From Lachish?”, 6-8, with comparative evidence from Arad, notes that “the names of the senders and the recipients were not always mentioned”.

[38] J. M. Lindenberger, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003), 117-118. I note that D. Winton Thomas, The Prophet in the Lachish Ostraca (London: The Tyndale Press, 1946), 19-20, was against theories which supposed the ostraca to be an interrelated group.

[39] 7.001 in Ibid, 76-77. Regarding the genre of this inscription, see F. W. Dobbs-Allsopp “The Genre of the Mecad „ashavyahu Ostracon” BASOR (1994): 49-55.

[40] Moussaïeff Hebrew Ostracon #2. Cf. Lindenberger, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, 110-111; Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions Vol. 2, 25-26, (99.008).

[41] Jeremiah 36 offers evidence of social and legal literate practices. In Jer 32:10-14, a purchase is sealed with a seal according to ‘commandment/law and statute/custom’.

[42] Lindenberger, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, 117-118.

[43] LL3: ‘. . . the heart of your [ser]vant has been sick ever since you sent (it:[the letter])’.

[44] ‘By the life of YHWH’ (Hy-YHWH) occurs 43x in the HB. In Jeremiah Hy-YHWH 8x, and Hy-´Dny YHWH 1x. Hos 4:15 is the only other case of Hy-YHWH in the Prophets, associating with ‘swear’ as in Jer 4:2; 5:2; 12:16.

[45] To date, bêt midrāš – “school” – is found no earlier than in post-exilic Sir. 51:23.

[46] 1.024.1 in Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 9, and 265 consists of the sequence: ´bgd {or ´bgr}.

[47] Ibid, 1.023, dated 8th cent.; A. Lemaire, “A Schoolboy’s Exercise on an Ostracon at Lachish” Tel Aviv (1976): 109-110 interprets it as a schoolboy’s exercise.

[48] A. Lemaire, Les Écoles et la formation de la Bible dans l’ancien Israël (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1981), especially 7-33, cited in G. I. Davies “Were there schools in ancient Israel?” in Wisdom in Ancient Israel (eds. J. Day, R. P. Gordon, and H. G. M. Williamson; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 199-211 (204-205).

[49] Davies “Were there schools in ancient Israel?”, 210-211.

[50] Jer 52:25 (cf. 2 Kgs 25:19) the ‘captain of the army’ – Sr hcB´ – had his own scribe. See “sōpēr” in G. J. Botterweck, et al, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 318-326; note, 324, regarding Jer 36:10, 20 ‘the chamber of the scribe’.

[51] LL4.3 includes ‘I have written on the tablet’ (ktbty `l hdlt). The word dlt is associated with writing in Biblical Hebrew in Jer 36:23.

[52] See C. A. Rollston, “The Phoenician Script of the Tel Zayit Abecedary and Putative Evidence for Israelite Literacy” in Literate Culture and Tenth-Century Canaan: The Tel Zayit Abecedary in Context (eds. R. E. Tappy and P. K. McCarter; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2008), 61-96 (61-63), for a definition of literacy for the southern Levant during antiquity.

[53] See R. Deutsch, Messages from the Past: Hebrew Bullae from the Time of Isaiah Through the Destruction of the First Temple (Tel Aviv: Archaeological Center Publications, 1999), 15, regarding inscriptional evidence for a large literate population in this First Temple period.

[54] I. Young Diversity in Pre-exilic Hebrew (Forschungen zum Alten Testament 5; Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1993), 110.

[55] P. G. van der Veen, The Final Phase of Iron Age IIC and the Babylonian Conquest (Bristol: PhD., Bristol University, 2005), 20, takes `BD hmlK/`BD mlK to be a title of a courtier. I thank Dr. van der Veen for providing me with a copy of his work.

[56] In LL3.13-14 it may be Hawsha‛yahu who was ‘told’ – hgd (cf. lhgd in LL3.1-2) –, by word of mouth and not by letter about Coniah, the son of Elnathan and captain of the army – Sr hcB´ – going down into Egypt.

[57] Regarding social levels of literacy, intelligibility and the HB, see Dever “Social Structure in Palestine in the Iron II Period on the Eve of Destruction”, 426.

[58] G. B. Sarfatti “Hebrew Inscriptions of the First Temple Period: A Survey and Some Linguistic Comments” Maarav (1982): 55-83 (58).

[59] P. G. van der Veen, “Gedaliah ben Ahiqam” in New Seals and Inscriptions, Hebrew, Idumean, and Cuneiform (ed. M. Lubetski; Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2007), 55-70.

[60] Van der Veen, The Final Phase of Iron Age IIC and the Babylonian Conquest, 246. Cf. Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 154, Lachish bulla 100.257 (late 7th cent.)

[61] Ussishkin, The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish, 4:2113.

[62] LXX has shmei/on for tafm/mś´t.

[63] N. H. Tur-Sinai [Torczyner], Lachish I: The Lachish Letters (London: Oxford University Press, 1938).

[64] Z. B. Begin, “Does Lachish Letter 4 Contradict Jeremiah XXXIV?” VT (2002): 166-147. For another recent view see Lindenberger, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, 117.

[65] So Emerton, “Were the Lachish Letters Sent to or From Lachish?”, 14.

[66] Mareshah was one of the cities suggested by D. Winton Thomas, The Prophet in the Lachish Ostraca, 11-12. Begin supports his case by citing a Hebrew ostracon recently found in Mareshah, reported in Eretz-Israel (1999):147-150, that attests the presence of Judahites there in the 7th century BCE. Micah 1:14-15 mentions ‘Mareshah’ and connects with ‘the houses of Achzib’. LL8 (reverse) has ‘house of Achzib’.

[67] Emerton, “Were the Lachish Letters Sent to or From Lachish?”, 4-5.

[68] K. A. D. Smelik, “An Approach to the Book of Jeremiah” in Reading the Book of Jeremiah: A Search for Coherence (ed. M. Kessler; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2004), 1-12, (1).

[69] Lindenberger, Ancient Aramaic and Hebrew Letters, 116.

[70] The biblical näbî´ (נָבִיא) is spelt with the mater lectionis ‘yod’ (י), but such an omission is common in inscriptional paleo-Hebrew. However, two bullae have been found in Lachish, dated “late 7th cent.” Having ‘nby[ ]’ with ‘yod’, but the final ‘aleph’ is missing (cf. Davies, Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions, 437, 100.258.3).

[71] Uriah, who prophesies earlier (Jer 26:20), has a Yahwistic theophoric name. He is not called a prophet.

[72] D. W. Thomas, The Prophet in the Lachish Ostraca, 21.

[73] In the HB, ‘the prophet’ – hnby´ – occurs 123 times, but Jeremiah has the highest concentration of uses, 44 times. In other Prophetic books the next highest is 5x in Ezekiel and in Haggai. Jeremiah is ‘Jeremiah the prophet’ 32 times.

[74] Jeremiah has by far the highest concentration of šm‛-related words in the HB. Their deployment argues for ‘hear(ken)’ being a key theme.

[75] „y YHWH occurs 8x in Jer 4:2; 5:2; 12:16; 16:14, 15; 23:7, 8; 38:16. Other prophets: Hos 4:15, only.

[76] R. P. Gordon, The God of Israel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 3.

[77] Pardee, Handbook of Ancient Letters: A Study Edition, 77-78.