Introduction

In a previous article we highlighted the fact that Biblical Hebrew is often employed to assign a date to OT books and we highlighted several methodological problems with this approach.[1]

A basic premise behind linguistic dating is that as languages evolve over time, they develop new words or syntax and incorporate loan words; in theory this allows a chronological time line to be established, which then can be used to date a specific piece of writing. This is important as it allows scholars to accord several biblical books a “late” date.

Books such as Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Job and many of the Psalms (and other books) are perceived to be “late” books, that is, they are dated after the burning of the temple (in 586 BCE) and after the Babylonian exile. Usually they are said to be dated in the Persian period (Ezra/Nehemiah) or even later. Does this matter? If the intertextual and contextual evidence of a Psalm or an OT book points to an earlier date then we have a problem. If the Hebrew language suggests a late date and the context suggests an earlier date then one of the two is wrong and this makes it impossible to reconstruct the original setting. For example, if the language of a Psalm suggests a “late” date of composition, but the context and ascription attributes a Psalm to David we face a “contradiction”.

The discipline of Biblical Hebrew linguistics includes philology, semantics, syntax, etymology, morphology etc. and is specialised and therefore the layperson is dependent on conclusions drawn by others. However, recent studies demonstrate that the scholarly consensus on the conclusions of linguistic dating is being challenged and starting to shift. The impetus for writing this article is as background for the two articles on the Songs of Degrees, or Songs of Ascent (Psalm 120-134); many of these Psalms are dated to the postexilic period, despite intertextual evidence for a much earlier date.

For example, the OT scholar, John Day, employs a linguistic argument to determine a late date for many of the Songs of Ascent:

An interesting example concerns the use of the Hebrew relative particle še instead of the normal classical Hebrew form ’ášer. Whilst this can be early, as its presence in Judges 5 suggests (cf. v.7), the fact that it became the regular relative particle in Mishnaic Hebrew proves that it could also be a late form, and such it surely is when it occurs in the Psalter. It appears there in some of the Psalms of ascent or steps (Pss 122.3; 123.2; 124.1, 2, 6; 129.6, 7; 133.2, 3), as well as in Pss 135.2, 8, 10; 136.23, 137.8, 9 and 144.15. Of these Psalms 124, 133 and 144.12-15 already appear in Hurvitz’s list of indubitably late psalms and Psalm 135 has been adjudged post-exilic above on the basis of its reference to the ‘house of Aaron’ in v.19 (cf. Ps.133.2), whilst Psalm 137 clearly reflects the experience of exile. Add to this the observation that all the instances of še in Psalms occur in the last third of the Psalter, where cumulative evidence indicates that a large number of late psalms are concentrated, and the case becomes overwhelming that all psalms containing še are no earlier than the exile, and apart from Psalm 137[2] are very likely post-exilic.[3]

The classical study on this topic referred to in scholarship (see Day above) is by Avi Hurvitz, who examined the linguistic signature of much of the OT literature and devoted a study to the Psalms published in the Hebrew language.[4] This is the foundational study for Hurvitz’s method of identifying “Late Biblical Hebrew” (LBH). A summary, focusing on methodology, was published in English.[5] More recently Hurvitz’s methodology has been challenged by G. A. Rendsburg,[6] I. Young,[7] R. Rezetko, and M. Ehrensvärd.[8] Whereas the traditional opinion, represented by Avi Hurvitz, believes that Late Biblical Hebrew was distinct from Early Biblical Hebrew (EBH) and thus one can date biblical texts on linguistic grounds, the more recent view argues that Early and Late Biblical Hebrew were merely stylistic choices through the entire biblical period. Young and Rezetko state,

LBH [is] merely one style of Hebrew in the Second Temple and quite possibly First Temple periods. Both EBH and LBH are styles with roots in preexilic Hebrew, which continue throughout the postexilic period. ‘Early’ BH and ‘Late’ BH therefore, do not represent different chronological periods in the history of BH, but instead represent coexisting styles of literary Hebrew throughout the biblical period.[9]

Moreover, the situation is complicated by dialect, colloquialisms and archaisms.

The “shin” particle

We will look at a case study on the “shin” particle še (שׁ) as this is often employed for dating purposes in the scholarly literature (again, see Day above). Many of us read the KJV version of the Bible; the language is beautiful, as it is the English of Shakespeare. Unfortunately, many of the terms are archaic English as the meaning of the word has changed in the evolution of the language. Let us say that we found a few lines of a poem that used the pronouns “thee” and “thou” instead of “you”. Could this poem be contemporary with Shakespeare? Yes, it might be, but it could also be a deliberate stylistic choice. The poet may be introducing “archaisms” for stylistic reasons. Then again it might be written by a native Yorkshire man from the older generation who still uses “thee” and “thou” in everyday speech. In that case we are speaking of a dialect or a colloquialism.

We have chosen the “shin” particle še (v) as a case study as it is frequently referred to in scholarly literature as an indicator of a “late” post-exilic date. The comments below are a synopsis from two articles by R. D. Holmstedt and the reader is referred there for a comprehensive treatment of the subject.

The data suggests that ’ášer was gradually replaced with še and therefore occurrences of še suggest a late date. While there are about 5,500 ášer clauses in the Hebrew Bible, there are only 139 occurrences of še. Of these, 68 are in Qoheleth and 32 are in Song of Songs;[10] 21 are in various psalms from Psalm 122 onward, and the remaining 18 are scattered in the Hebrew Bible, literally, from beginning to end.[11] In his 2006 study Holmstedt argues that ášer has a single function throughout ancient Hebrew: to nominalise clauses,

In other words, in relative clauses ášer nominalises a clause so that it may function as an adjective-like modifier of a noun (e.g., the man that….), and in complement clauses ášer nominalises a clause so that it may function as a complement noun (e.g., the fact that…) or verb (e.g., he swore that…).[12]

Holmstedt concludes that,

Concerning the extreme few examples of ášer that are often analysed as something other than relatives or complements, all but a handful can be analysed as relatives (either simple, null-head, or extraposed). And second, it does not appear that there are any demonstrable changes in the use of the word from the earliest attested stage of Hebrew through to the Mishnah; in other words, ancient Hebrew ášer did not undergo reanalysis.[13]

Perhaps his most important observation is the following:

In fact, given the numerous recent challenges to the three-stage model, as well as the greater interest in identifying remnants of a northern dialect of Hebrew in the biblical material, we should perhaps refrain from making any strong statements on the supposed grammaticalisation of ášer from the early to the later stages.[14]

In other words the introduction of še (from northern origins) did not change the use of ášer (no grammaticalisation) either in early or late Hebrew. It would seem then that ášer and še were employed side by side (interchangeably?) without necessitating syntactical transformation (which we would expect with a substitution). On the origins of še Holmstedt has the following to say,

Accounting for the variation between rva and v/ typically weaves diachrony, dialect, and stylistics together. Since Gotthelf Bergsträsser’s (1909) “Das hebräische Präfix v,” it has been the scholarly consensus to trace the etymology of Hebrew v from the Akkadian relative ša. It has since become generally accepted that the route between Akkadian ša and what we find in the Hebrew Bible goes through northern Canaanite (for example, Phoenician) and then northern Hebrew. The northern connection has been suggested in particular to account for the appearance of v in Judges 5–8 (5:7; 6:17; 7:12; 8:26), as well as the single occurrence in 2 Kgs 6:11. By combining the northern origin view with diachrony, the following reconstruction is common: v became the relative word of choice (perhaps originally by borrowing from Phoenician), by change and diffusion, within some Hebrew grammar in the north (which presumably also already had rva), from which it influenced some southern grammar, particularly after 722 B.C.E., so that eventually it replaced rva (see Kutscher 1982: 32, §45; Davila 1990; Rendsburg 2006; compare Bergsträsser 1909).

Alongside the dialectal and diachronic perspectives (and in some tension with them) are the register and style proposals. For register, some have identified v as the colloquial Hebrew relative word and dva as the literary choice (Bendavid 1967: 77; see also Joüon 1923: 89; Segal 1927: 42–43). Taking this a step further, Gary Rendsburg has situated this variation within a diglossia analysis, suggesting that rva reflects the “High” variety and v reflects the Low” variety that had somehow made its way into a formal, written context (Rendsburg 1990: 116–18; Davila 1994). For style, Davila has suggested that the use of both rva and v is a literary device: “the impression we get [of the author of Qoheleth] is that he was a proud iconoclast, and it is not hard to imagine him as a sage who insisted on talking like real folks and not the highbrows in Jerusalem” (Davila 1994). In Young and Rezetko 2008, the stylistic analysis is taken a step further: the use of v is identified as “substandard” Hebrew in the service of the “unconventional writing” of an “unconventional thinker” (2008: 2.65) and denied any diachronic relevance (2008: 1.214, 227, 247)”.[15]

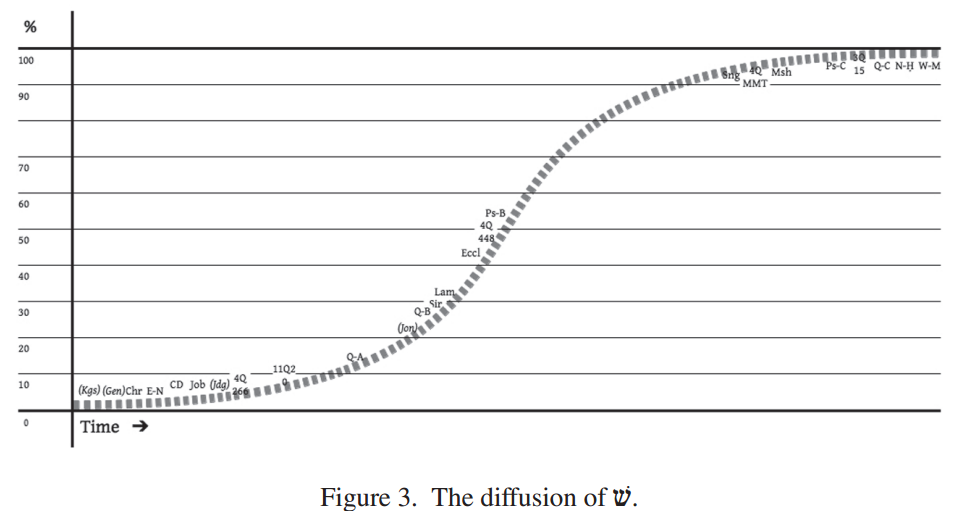

Holmstedt employs biblical and extra biblical sources (such as Qumran, Mishnah etc.) to plot the distribution of v and a typical S-curve emerges (see Figure 3 below).

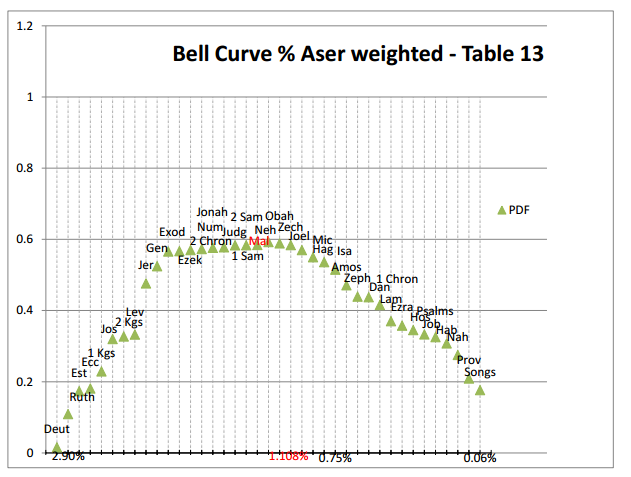

For the purpose of his analysis Holmstedt has split the Psalms into three different groups (Ps-A, Ps-B and Ps-C) and as we can see Ps-B and Ps-C groupings appear late on the S-curve. This seems to confirm his argument that, for example, the grouping of Ps-C is of late origins as it contains nearly the same percentage of “shin” particles as the Mishnah (MSH), which is known to be a late writing. Ecclesiastes (Ecc) and Songs (Sng) also seem to be “late” postexilic books. However, there are problems with the methodology and with the interpretation of the data. If the biblical data is weighed and analysed[16] as a PDF (Probability Density Function; see diagram below) a skewed platykurtic form of the normal distribution emerges demonstrating that both high and low occurrences of ášer fall within a standard population range and therefore do not indicate an increasing trend in the usage of ášer .[17]

Conclusion

Although linguistics is a useful tool and is probably helpful in establishing relative dates (books that are prior), without accompanying intertextual and socio-historic evidence, it cannot establish absolute dates. The available data is open to interpretations other than diffusion and care must be taken to avoid methodological errors that bias the presentation of the data. Using the same data we conclude that the emergence of the “shin” particle was not due to a slow diffuse process but rather by a rapid adoption of northern Israelite scribal practices (by Judean scribes) caused by the influx of northern refugees after the fall of Samaria and the Assyrian crisis during Hezekiah’s reign.[18]

[1] See P. Wyns “Song of Songs (Part 1)” CeJBI 7/3 (2013): 4-11.

[2] Day considers that Psalm 137 was written during the exile not afterwards.

[3] J. Day, “How Many Pre-Exilic Psalms Are There?” in In Search of Pre-Exilic Israel: Oxford Old Testament Seminar, (ed., John Day, London: Continuum, 2004), 243.

[4] Avi Hurvitz, The Transition Period in Biblical Hebrew: A Study of Post-Exilic Hebrew and its Implications for the Dating of Psalms, [Hebrew], (Jerusalem: Bialik, 1972).

[5] Avi Hurvitz, “Linguistic Criteria for Dating Problematic Biblical Texts” Hebrew Abstracts 14 (1973): 74-79.

[6] G. A. Rendsburg is best known for his attention to the northern Hebrew dialects within BH, and what he terms Israelian Hebrew (IH). He extends Hurvitz’ method of analyzing ‘Aramaisms’ to possible dialectal differences between the northern Israelian dialect and the southern Judean dialect. See his “Hurvitz Redux: On the Continued Scholarly Inattention to a Simple Principle of Hebrew Philology” in Biblical Hebrew: Studies in Chronology and Typology (ed. I. Young; London: T&T Clark, 2003), 104-128.

[7] Young argues against a linear development in his edited volume, Biblical Hebrew: Studies in Chronology and Typology.

[8] I. Young, R. Rezetko and M. Ehrensvärd Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts. An Introduction to Approaches and Problems (2 vols; London-Oakville: Equinox, 2008).

[9] Young & Rezetko, Linguistic Dating of Biblical Texts. An Introduction to Approaches and Problems, 2:96.

[10] Qoh 1:3, 7, 9 (4×), 10, 11 (2×), 14, 17; 2:7, 9, 11 (2×), 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 (3×), 19 (2×), 20, 21 (2×), 22, 24, 26; 3:13, 14, 15, 18 (šĕ), 22; 4:2, 10; 5:4, 14 (2×), 15 (2×), 17; 6:3, 10 (2×); 7:10, 14, 24; 8:7, 14 (2×), 17 (šel); 9:5, 12 (2×); 10:3, 5, 14, 16, 17; 11:3, 8; 12:3, 7, 9. Song 1:6 (3×), 7 (2×), 12; 2:7, 17; 3:1, 2, 3, 4 (4×), 5, 7, 11; 4:1, 2 (2×), 6; 5:2, 8,9; 6:5 (2×), 6 (2×); 8:4, 8, 12.

[11] Pss 122:3, 4; 123:2; 124:1, 2, 6; 129:6, 7; 133:2, 3; 135:2, 8, 10; 136:23; 137:8 (2×), 9; 144:15 (2×); 146:3, 5. Gen 6:3; Judg 5:7 (2×); 6:17; 7:12; 8:26; 2 Kgs 6:11; Jonah 1:7, 12; 4:10; Job 19:29; Lam 2:15, 16; 4:9; 5:18; Ezra 8:20; 1 Chron 5:20; 27:27.

[12] R. D. Holmstedt, “The Story of Ancient Hebrew ášer” ANES 43 (2006): 7-26 (14).

[13] Holmstedt, “The Story of Ancient Hebrew ášer”, 21.

[14] Holmstedt, “The Story of Ancient Hebrew ášer”, 13.

[15] R. D. Holmstedt, “Historical Linguistics and Biblical Hebrew” in Diachrony in Biblical Hebrew, (eds., Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé and Ziony Zevit, (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2012), 97-126 (116-117).

[16] Holmstedt’s non-biblical data has been omitted and the Psalms (although heterogeneous) have been analysed as a group.

[17] The data is analysed in a spreadsheet which (together with an explanation) is available for download.

[18] The conclusions in this article are based on statistical work; available as an Excel spreadsheet (Aser and Shin Distribution in the OT) on the ‘downloads’ page of the EJournal website.