The coming to the British Museum of relics from the tomb of the Egyptian Pharaoh, Tutankhamun, is a signal event for all who are interested in the archaeology of Bible lands and it may be helpful to some visitors to the Exhibition to indicate the historical background which accompanied the monarch’s reign and contributed to his life and death.

The period of history concerned was marked by a great religious conflict in Egypt. The story starts in the city of Thebes which was, for generations, the headquarters of the priests of Amun, whose name means “the hidden one”. The priests dominated the Egyptian scene, and even the monarchs had to respect their authority. This fact is illustrated by an inscription on an obelisk erected by Queen Hatshepsut at Karnak, across the Nile from Thebes, described as “a world of temples”. The inscription reads:

“Concerning the two great obelisks, which my majesty has had covered with electrum for my father Amun, that my name may live for ever in this temple throughout the centuries, they are hewn from a single stone, which is of hard granite with no joints … I have shown my devotion to Amun as a king does to all the gods. It was my wish to have them cast in electrum (as this was not possible) I have, at least, placed a surface (of electrum) upon them.”

According to Bible records, the Exodus took place 480 years before the fourth year of King Solomon’s reign, about 957 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1); and the time when the Israelites were refused entry into the country of the Amorites, during their journey from Egypt to the Promised Land, was 300 years before the time of Jephthah, which was about 1100 B.C. These figures indicate that the date of the going out was about 1440 B.C. In this case it seems not unlikely that Hatshepsut was the princess who took the infant Moses from the Nile.

Hatshepsut was “the first great woman of whom we have knowledge”. She reigned with all the attributes of a Pharaoh and one of those most affected by her strong rule was her brother Tuthmosis, who was under her tutelage. After many years of this frustration he decided that she must be deposed in favour of himself. To bring this about he enlisted the support of the “king-makers”, the priests of Amun, and with their help he was able to ascend the throne as Tuthmosis III. Again, on the Scripture evidence, he would be perhaps the chief Pharaoh of the Oppression of the Hebrews. It •must be remembered that the Oppression lasted for many years and that several monardhs shared the guilt of it.

Tuthmosis, however, was not content to be entirely subject to the priests, and he was probably the first monarch to make a countermove to their domination. He warned them, by planning to erect an obelisk to the Sun god, that they could not do exactly as they liked. The immense stone needle to the rising sun was not erected during his lifetime, nor was it set up by his successor, Amenophis II. On the evidence already quoted Amenophis would be the Pharaoh of the Exodus.

Tuthmosis IV

The next Pharaoh was Tuthmosis IV. He erected the obelisk, prepared by his grandfather, and was apparently able to provide some kind of compromise between the priests of Amun and the scholar-priests of the sun, who worshipped at the city of the sun, Heliopolis (the On of the Bible). An interesting discovery about this monarch is at least in line with the possible date of the Exodus, already suggested. At the breast of the Great Sphinx at Gizeh, there is a monumental stele, or slab, placed there by Tuthmosis IV. The inscription on the stele indicates that he was not originally in the line of succession. It states that one day when he was hunting in the

Memphis area, he fell asleep at noon in the shadow of the Sphinx. Re-Harmakhis (Horus in the Horizon) appeared to him in a dream. The god was suffering beneath the heavy weight of sand and told Tuthmosis that, in exchange for deliverance from the intolerable burden, he would ensure that his benefactor would wear the double crown of the reigning monarch, Amenophis II. As soon as he awoke, Tuthmosis drove home and ordered that the god should be freed from the burden of sand. According to the legend, which may be the way in which Tuthmosis justified his claim to the throne, he forced the priests of Amun to hail him as the new Pharaoh. An earth-brick wall, built by Tuthmosis to keep the desert sands from the Sphinx has been unearthed. All the bricks bear his royal stamp.

Thus, Tuthmosis was not the crown prince and had, before his dream, no expectation of becoming Pharaoh. The crown prince could have been killed in the slaying of the firstborn as described in the Bible.

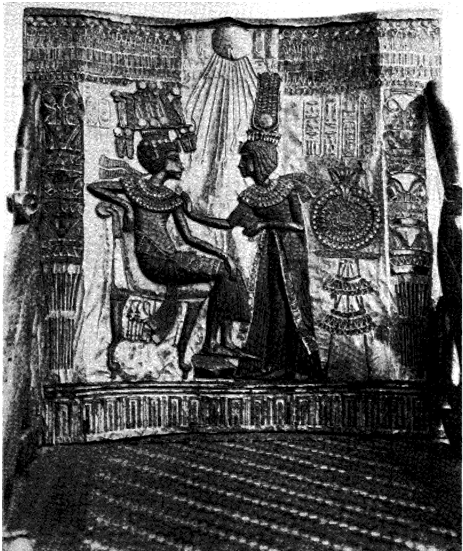

Gold panel from the back of throne depicting Tutankhamun and his queen Ankesenamun. Sheets of gold and silver are used with coloured glass paste, glazed ceramic and inlaid calcite.

Amenophis III

The successor of Tuthmosis IV was Amenophis III. There is evidence that, at least to some extent, he favoured the worship of the new god of the sun, Aten. He founded a temple called Gem-Aten and his royal barge, as well as one of his regiments, was called “Splendour of Aten”. His chief wife, Tiy, was a commoner; her parents Yuha and Thua were priestly dignitaries in the service of Amun. They were of Nubian origin, coming from the country to the south of Egypt. Although Amenophis had many wives, Queen Tiy remained the chief spouse and bore him a number of children. She seems to have been a forceful and energetic character. Her husband, who reigned for about 40 years, was rather more passive.

Akhenaten

From this time forward the march of events is obscure, and it is not possible to be certain exactly what happened. It seems likely, however, that toward the end of his reign Amenophis established a regency with the son presented to him by his wife Tiy. At that time the son’s name was Amenophis, and when his father died he ascended the throne as Amenophis IV. Like his father he seems to have married a commoner, Nefertiti, though a number of theories have been put forward as to her origin. Her portrait has been produced so many times that she is the best known of Egyptian queens, known to more people than her illustrious predecessor, Hatshepsut. Not many facts about her life are available, however, and she has been described as the most famous and least known of queens. She was one of the most beautiful women of her time. Her name means “The lovely one has come”.

With the advent of the new king, the struggle between the priests of Amun and the followers of the cult of Aten was intensified. From the first, Amenophis was a worshipper of Aten. At Karnak, just across the Nile from the headquarters of Amunism, he built a temple which he called “Aten is found in the house of Aten”. Soon, he went further and proscribed the worship of Amun and other state gods. He moved the capital from Thebes to a site on the banks of the Nile in Middle Egypt. Here he built a city, which, in spite of its hasty construction, was a dream of palaces, temples and small houses, nearly all surrounded by superb gardens. He called it Akhetaten, “The Horizon of Aten”: Aten was shown in sculptural representations as the sun’s disc, with rays ending in hands, holding the ankh or life sign. Amenophis changed his name to Akhenaten, “the glory of the solar globe” or, possibly “the effective spirit of the Aten”.

The teachings and moral principles of Atenism have not yet been discovered, even if they existed. The king constantly described himself as “Living in Truth”. He recognised at least, Moot, whose name means truth, truth being regarded as “order” or “reality”. The king’s purpose was at first supported by his wife, Nefertiti, and he extended her name with the words, “Fair is the goodness of Aten”. Tiy, the queen mother, also supported him, but she died during his reign. A further strong ally of the king was his vizier, Ay, whose origin is obscure. He was known as the “Divine Father”.

Towards the end of his seventeen years reign, Akhenaten suffered many set-backs. The priests of Amun were always hostile, and it seems that he had a disagreement with Nefertiti, who left the royal palace and went to live in the north part of Alchetaten. In the British Museum is an inscription which once bore the joint names of Akhenaten and his queen, but the latter’s name has been scored off.

During the reigns of Amenophis and Akhenaten, the prosperous empire which they had inherited began to decay, though Egypt had many vassal kings in Canaan and Mesopotamia. In Akhenaten’s time the correspondence of the Egyptian Foreign Office was carried on from Akhetaten.

The king’s endeavour to establish the worship of Aten did not long survive him. Soon, his magnificent capital was covered with sand and entirely lost. In 1887, however, there were discovered on the site (now called Tell el Amarna), in the House of the Royal Rolls, letters written in cuneiform (wedge-shaped) characters on clay tablets, three hundred in number.

The letters proved to be the communications received by Akhenaten from vassals in Canaan and Mesopotamia. Those received from Canaan are specially interesting, since among them are appeals for help from the local inhabitants against a people called the Habiri, who were ‘attacking them and capturing their cities. Biblical names are included such as Lachish, 1Gezer and Aijalon. Abdi-hiba, king of Jerusalem is one of the writers, and it is suggested that Abdi-hiba is the Hittite equivalent of Adoni-Zedek.

There is at least a possibility that the Habiri mentioned in the letters are the Hebrews. In fact J. W. Jack writes, “If the term Habiri does not mean Hebrew, then no name has been found in Babylonian or Assyrian to designate this important people”.

Whether Akhenaten would ever have been able to establish his worship of Alen for an indefinite period seems very doubtful, but, in any case, his reign was not long enough to make it possible.

Smenkhare and Tutankhamun

It appears that, in the last few years of his rule, Akhenaten associated a young man, Smenkhare, with himself as co-regent. Who this young man was is not clear, but a modern examination of the skeletons of Smenkhare and Tutankhamun suggests very strongly that they were brothers and, very possibly, half-brothers of Akhenaten.

When Akhenaten died, Smenkhare, being the eldest of the two brothers, became Pharaoh. He did not reign for long, however; he died in the same year as Akhenaten, leaving the throne vacant for Tutankhamun, then a boy of about nine years old. He reigned for only nine years. The presence of so young a ruler gave the priests of Amun the opportunity to endeavour to restore their authority. Even during the shorl reign of Smenkhare, negotiations had begun and the “Divine Father”, Ay, possibly with a view to promoting his own interests, supported them. The original name of Tutankhamun had been Tutankhaten, but early in his reign, the king forsook Akhetaten and moved to Thebes with his queen. He changed his name to the one by which he is so well known. His queen was Ankhesenamun, previously Ankhenespaaten. Little is known of the reign of Tutankhamun, yet he is the most famous of all Pharaohs because his tomb largely escaped the attentions of tomb-robbers.

Upper portion of the third mummiform coffin, that containing the body of Tutankhamun made of beaten 22 carat gold. Measurements 188ins. x 50ins. x 50ins.

Ay’s foresight stood him in good stead; he succeeded Tutankhamun and reigned for four years. It is possible that, in order to reinforce his claim to the throne, he married Tutankhamun’s widow, Ankhenesamun. One of the thief advisers of Tutankhamun was Horemheb.

This man had served Akhenaten in Lower Egypt and later had collected Tutankhamun’s revenues in Asia, particularly in Palestine.

Horemheb

When Ay died, Horemheb was ready to seize the throne. He was a far different character from his predecessors and began a new era of positive government in Egypt. He brought the prosperity of Akhetaten and Akhenaten’s attempt to instal the worship of Aten to an end. The names of the monarch were eradicated from the records of the laws and his name was also hacked out of texts wherever it occurred. The city was dismantled with many of its buildings. Moreover, Horemheb did his utmost to obliterate Tutankhamun from human memory. He removed his name from statues Which he had made and substituted his own. One statue of Tutankhamun, wearing a leopard skin and standing before Amun in the attitude of a monarch who had just lost his father, he smashed. Curiously enough, Tutankhamun’s tomb was not sacked, and this fact, together with the modern activities of Lord Carnarvon and Mr. Howard Carter, shows that the curse of Horemheb ion the young Pharaoh was futile; ironically, Tutankhamun became the most famous of all the rulers of Egypt.

Ankhenesamun, who had survived three husbands—Akhenaten (her father), Tutankhamun and Ay—was now threatened with the possibility of marrying Horemheb, a commoner. The prospect filled her with dismay. She did not, she said, wish to take a “servant” as a husband. To avoid this she entered into negotiations with the Hittites to marry their prince, Zanannza, who would thus become Pharaoh. The negotiations had started when Ay was on the throne, and were most likely encouraged by him. Horemheb was aware of what was taking place, and when Zanannza set out for Egypt he was met by the agents of Horemheb and murdered. Whether the widow ever married Horemheb is not known. At this point she disappears from history, perhaps also murdered by the ruthless Pharaoh.

Was Tutankhamun murdered ?

Two matters of interest, among many others, arise from Tutankhamun’s tomb. The X-ray pictures of his mummy revealed a small piece of bone in the left side of the skull cavity, and they also suggest that the piece is fused with the overlying skull. This is consistent with a depressed fracture which had healed. These facts could mean that he died of a brain haemorrhage caused by a blow from a blunt instrument. The monarch was only eighteen when he died. Was he murdered? He had many enemies, including the ambitious Horembeb.

Another mystery arises from the fact that some of Smenkhare’s burial furnishings were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb. These include little golden sarcophagi containing Tutankhamun’s viscera. On these were still visible traces of the name of Smenkhare. There were also gold bands, binding Tutankhamun’s shroud, from which the name of Smenkhare has been scratched out.

The “Divine Father”, Ay, was responsible for the burial of Tutankhamun. It is hard to see why anyone should have chosen for the boy monarch things so intimately associated with the mummy and viscera of his predecessor. The young king, whose treasure was so vast, had no need to steal from a corpse.