Introduction

L. Bedwell advocates[1] the Septuagint [LXX[2]], a Greek OT translation of the Hebrew Bible, as the source for the theological vocabulary and propositions of 1 Peter. Bedwell is an advocate of the view that not only is “Peter an assiduous student of the Greek Old Testament” but that “in general [Peter] quotes from [this] Greek version of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint (LXX) rather than from the original Hebrew Scriptures”. Listing “Quotations in 1 Peter from the Septuagint” to support his view, he adds that they are “more or less direct quotations” from the LXX. Such observations, among others, determine that “Peter’s mind was saturated with the LXX…[that it] had become so much a part of his mentality that his letter was stamped with its impress”. Given Peter’s Jewish Galilean background, and the fact that the odd quotation could derive from the Hebrew Scriptures, or from either (Greek or Hebrew) OT version (e.g. Lev 11:44 in 1 Pet 1:16) he concludes that “…it is inescapable that Peter was familiar with the Old Testament in the Greek as well as in the Hebrew”.

This raises issues of fundamental concern. Foremost is how a view of verbal inspiration as expressed in a statement of faith such as the BASF could apply to, or see the NT as using, an uninspired translation. Bedwell’s[3] article favouring (what without differentiation he calls) the LXX, and advertised as ‘Echoes of the Septuagint’, is the most obvious of recent years to uncritically import scholarly views on the use of the LXX into the community.

My view-point is that this matter should not be left unchallenged, or dismissed as being of merely academic interest. Bedwell’s approach aligns with entrenched theological perspectives presented in commentaries, but does not benefit from intertextual insights, or caution, derived from specialised research. Since the beginning of the Brotherhood’s history brethren have made some, mostly minimal, use of the LXX;[4] yet its spiritual relevance or textual integrity are rarely questioned or qualified. Therefore, both a spiritual disinclination towards his case, or a challenge to it based on rigorous objections are sound responses.

Kurios

The LXX is a work (a heterogeneous collection, now as one corpus) that embodies much wrested Scripture: ‘adding to, or taking away from’ God’s inspired original meaning. An intertestamental translation is hardly likely to anticipate, or align with, New Covenant meaning in its deviations from the Hebrew Bible [i.e. MT]. I would contend, therefore, with similar data, that this accounts for how some NT quotations match the LXX:[5] post-NT editorial work interfacing with the NT created, or would relate to, what A. Rahlfs would call, “Christian additions”.[6] For example, the major use of kurios in the LXX,[7] that is no transcription of ‘Yhwh’ (in Hebrew characters) as in Qumran OT fragments or no Greek transliterations (like IAW), has been attributed by some to revisionary work in the LXX in the light of the NT.[8] This Judaeo-Hellenistic (ultimately ecclesiastical) product is not necessary for spiritual use; for academic interest, yes, in linguistic, theological and historical areas in relation to Judaic and later ‘Christian’ developments.

Convinced by our Scriptural ideology, resulting from using Scripture’s own proof procedure, we boldly challenge Christendom’s false doctrines, and yet some drift towards a conformist position over the claimed dependence of the NT on the LXX. However, such procedures are equally applicable to this, as to any matter. In response to this situation my selective remarks, both contend with Bedwell’s approach and have general application in this area.

1 Peter and the LXX

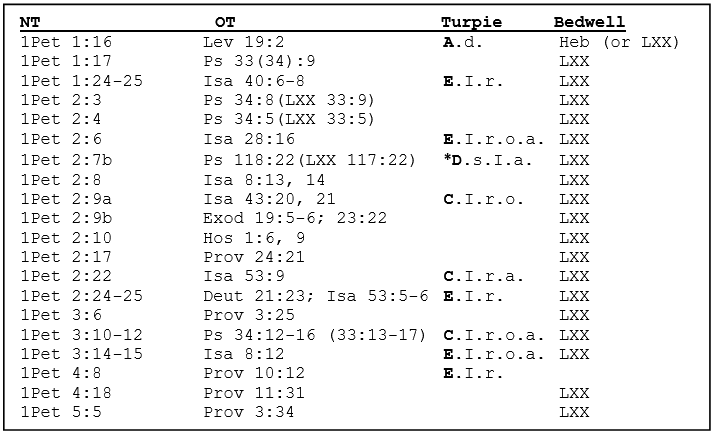

Once scholarly works are cited there is a need to reflect the range of opinion, contrary or otherwise, that might affect one’s conclusions. Bedwell’s presentation of Peter’s quotations as deriving generally from the LXX (see the listing in the table below his name) neglects certain standard works on quotation (e.g. Turpie’s, with his coding[9] of the proximity of NT to LXX or Hebrew, etc., in the list below) and more thorough textual analysis. He does not tell us, for example, what LXX version he is using (I suspect it is just Vaticanus, as in Brenton [Bagster, 1851]; see below), nor does he range through various manuscripts, or variant readings, within the LXX tradition. Lastly, his list of ‘quotations’ (below) do not show how he has decided that they are quotations:

Turpie has identified quotations from text that are self-evidently the OT reused, or because they have some introductory formula. Below, I give the totals for each quotation type and explain what that type is. (I just use Turpie’s initial letter, e.g. ‘C’, not “C. I. r. o”, to specify quotational type.)

Number of instances per quotational type:

- one (‘A’ type) quotation which shows the NT in alignment with both the LXX and Hebrew [MT];

- three (‘C’ type) quotations where the NT does not align with LXX and MT, but where LXX and MT agree;

- one (*’D’ type) quotation where the LXX and NT agree and they both differ from the Hebrew (viz.1 Pet 2:7b from Ps 118:22 (LXXPs 117:22);

- five (‘E’ type) quotations which divert from both LXX and MT, themselves not agreeing.

Note: NT aligning with MT only (‘B’ group) is not listed.

So, unlike Bedwell’s generalised approach: “Peter in general quotes from…the Septuagint (LXX) rather than the Hebrew Scriptures…[in these] more or less direct quotations” (p. 181), Turpie’s account is much more specific and contrary to Bedwell’s claim. Turpie gives just one quotation (Type ‘D’) as being in strict agreement with the LXX. Turpie’s list is typical of the problem scholars have over the NT quotations. They want to have it that the NT’s use of the LXX is one of the assured results of nineteenth century scholarship, but they are faced with the problem that the majority of quotations actually divert from the LXX and the MT.

According to Turpie’s classifying of quotations in 1 Peter, 80% of them show the NT to have diverted (lexically, grammatically, syntactically, etc.) from the OT (‘E’ 5 + ‘C’ 3 = 8). Attention to the other ‘quotations’ Bedwell gives as being from the LXX, and not covered by Turpie’s list, would equally breakdown into such differentiated categories, or options.

Bedwell adds other quotations in his main text. Some like “peace be multiplied” (1 Pet 1:2 from Dan 3:31 (4:1) and 6:25(26)) are used to reiterate that the LXX “had become so much a part of [Peter’s] mentality that his letter was stamped with its impress” (p.181). Yet had he checked the Aramaic of Daniel, (although a remark on p.180 suggests that he may not have known the original Bible languages), he would have seen that this form of words is actually in the original text. Thus, there is no necessary dependence upon the LXX. Finding this in the Aramaic might have complemented his urge to add that “Peter knew and used the Hebrew Scriptures as well”. However, he is ambiguous, or not analytically decisive, about a particular case he cites, 1 Pet 1:16: “It might have been taken from the Hebrew or the Greek, although it seems nearer the Hebrew….” Nevertheless, returning to his main emphasis, “the advantages in Peter’s knowledge of the LXX” (p.182), he asserts: “the conclusion is inescapable…Peter was familiar with the Old Testament in the Greek as well as in the Hebrew (p.181)”.

There are precedents in the Old Testament for mentioning by name books not included in the OT corpus. Similarly, in the NT, sayings of unnamed Greek poets are briefly cited,[10] but where is there a reference to ‘the Septuagint’ (or to a Greek OT translation at all)? These poets’ words have only strategic approval in the inspired apostle’s argument; Divine inspiration did not produce their remark. Divine sanction is not conferred upon their work(s). If the LXX is not named, does it come under the heading of ‘Holy Scripture’?! How could it? First, prove that the NT uses LXX material then prove that such usage implies, or guarantees, the Spirit’s imprimatur for that use.

Commentators use NT quotations which they claim derive from ‘the LXX’ as proof that the NT uses the LXX. This is obviously circular reasoning until it is proved to be the case that the NT uses the LXX. T. S. Green (1842) was actually more cautious about the NT’s resort to the LXX being confirmed by the NT quotations:

[The NT writers’, et al] acquaintance with the Septuagint or Alexandrian version is here assumed from its high intrinsic probability. A proof drawn from the quotations made in the New Testament could hardly be conclusive, on account of the possibility of an alteration of the text of the Septuagint by Christian hands, combined with the fact of the greater agreement between the quotations and the text of the Alexandrian MS than that of the Vatican. This alteration may not have arisen from a fraudulent motive, since there would be less scruple in interfering with a translation than an original, and it might be done with a desire to improve it in particular places on the authority of inspired writers. If any proof is attempted, it should be founded on passages, which, containing allusions rather that actual quotations, give no ground for suspecting intentional alterations.[11]

Bedwell’s simplistic embrace of the standard view of the LXX and intertextual relations does not raise such possibilities. A less narrow scan of commentaries and academic journals would reveal observations scattered throughout the literature which cumulatively give weight to Green’s view. This is not systematically addressed, however. Instead, when the possibility of NT influenced interpolation in the LXX is mentioned, the scholar concerned will foreclose (or sabotage) any enquiry by relying on the consensus view (e.g. C. Stanley, 1992[12]).

In fact, J. Ramsey Michaels, in his commentary on 1 Peter, although taking the standard line, at least mentions that the possibility of interpolation in 1 Pet 2:6 has been proposed:

So apt in fact is ep auto [‘upon him’] as a reference to Christ that some (e.g., Goppelt, 148) have regarded it as a Christian interpolation in the LXX (it is lacking in the MT and in LXXB).[13]

What role do we assign to the Holy Spirit in the production of Scripture? Is it seemingly all left to Peter, or such formative influences upon him, his mind being saturated with the LXX (as an “assiduous student” of the LXX)? Commitment to this way of representing the production of 1 Peter would not easily be dissociated from such views as: ‘Peter quotes from (his fallible) memory, or selectively from other works, this is why so many of his quotations diverge from the OT’. On the other hand, verbal inspiration understands God to be present in Peter interpretative transpositions, or to be revealing new (Christological) aspects to former expression. This is part of the concept of Biblical ‘quotation’.

The Holy Spirit given to Christ, to the NT preachers, believers (e.g. those speaking in tongues) and writers would not require use of a Hellenic translation in Greek to mediate the Spirit’s meaning in (or from) the original Hebrew. In any case, even on the natural plane, theirs was an Hebraic (or Semitic) milieu, not an exclusively Hellenistic one. Until Acts 10, Peter operated within the Jewish scope of his Lord’s ministry. Peter’s own reluctance to take the Gospel to the ‘common’ Graecised Gentiles is proof that he had not been modified by perspectives, propaganda policies, or exegesis, accepted today as present in the LXX. What evidence is there that he read the Greek LXX?

In Acts 4:13, Peter (with John) is described as “unlearned and ignorant” such that his audience “marvelled and took knowledge of [him] that [he] had been with Jesus”. In common with his Lord, he “taught with authority not as the scribes” (Matt 7:29).

The Greek word for ‘unlearned’ relates to someone who is not ‘lettered’, or not educated as a scribe would be; the scribes were learned. ‘Ignorant’ (Acts 4:13) is used of those who are uninitiated in some area of learning (1 Cor 14:23). So Peter was uninitiated in the kind of (approach to, or body of) learning which typified the lettered scribes. (Perhaps, the scribes might have encountered, or studied, the then extant form of the LXX, or Hebraizing revisions of it that some scholars now propose as possible sources for quotations which deviate from the ‘standard’ LXX). Peter through his Lord and Scripture was “taught of God” (John 6:45; cf. Isa 54:13). It would certainly be strange, therefore, if Peter had been, as Bedwell claims, “an assiduous student of the Greek Old Testament” (p.181); that it had contributed to his theological understanding.

Current research is much more cautious about assigning the name ‘Septuagint’ to a particular Greek OT translation; but this is rarely the case in theological commentaries.[14] Manuscripts or textual forms are classified in a more differentiated way. Since we have no copies of an original archetype (or whatever view is subscribed to of Septuagintal origins), scholarly interest has centred around isolating the ‘Old Greek’ in manuscript fragments, or in hypothetical reconstructions of the LXX utilising the ‘Christian’ codices of 4th-5th centuries A.D, and early Greek OT fragments mainly from the Judean desert. It is difficult to determine just how much of the Old Greek (original ‘LXX’) is reflected in the current text of the codices assigned the name ‘‘Septuagint’. It is also not yet finally clear how much of this version was available in NT times.

Some commentators who cite what they call ‘the Septuagint’ do not seem to be aware of these matters, or if they are it does not, as it should, affect their approach or conclusions. Bedwell’s material is reminiscent of Bagster’s 1851 publication of the LXX (with Lancelot Lee Brenton’s English translation), which is essentially Vaticanus (with its missing parts, e.g. Gen 1-46:28; Ps 105:27-137:6, supplied from other manuscripts). He does not cite critical editions, like Rahlfs’ (1935), or the more recent and respected Göttingen editions, so far produced. Stanley’s following remarks are wisely considered in any approach to ‘the Septuagint’:

The Greek version known today as “the Septuagint” is best regarded not as a single translation, but rather as a collection of translations prepared over the course of perhaps two and a half centuries, whose language, style, and mode of translation vary widely from book to book.[15]

It is said that the NT quotations claimed to derive from the Septuagint align more often with LXXA (i.e., Alexandrinus) rather than LXXB (i.e. Vaticanus 1209.) However, the 4th-5th century A.D. codices Vaticanus, Alexandrinus and Sinaiticus, often diverge from the Hebrew Bible, from each other, and often vary in OT passages quoted in the NT. The problem for scholars is not the few quotations which seem to agree with ‘the’ LXX, but the greater number which do not. Statistically, the NT diverges more from both the LXX and the MT and often when they are both in agreement.

“All Scripture” (2 Tim. 3:16) in both the Statement of Faith, or in “A Declaration” (1974) is taken implicitly to mean the Hebrew and Aramaic OT, and the Greek NT, since these ‘are’ (i.e., they represent in their present form) the Spirit’s originals. [‘Verbal’] Inspiration applies to the linguistic medium in which Divine revelation was delivered or recorded. This precludes a translation of the sacred text being inspired since those who produced it were not “moved by the Holy Spirit” to do so; God did not speak by, or in, them. This does not, of course, rule against inspired translation occurring within a sacred text, like the NT.[16] So, translations of the Hebrew OT and Greek NT (like English versions KJV, RSV, NEB, etc.) are not inspired, but where they are faithful to the originals are nevertheless truth preserving.

Since we maintain that there is theological (or Christological) symmetry between the Hebrew OT, which contains the “spirit of Christ” (1 Pet 1:11; cf. Luke 24:44-48) and Jesus as “the Word (of God) made flesh”, it would be incongruous (to say the least) to identify a Greek OT translation (with all its attendant corruptions and complex transmission history) as having such symmetry with “the Spirit of Christ” or with Christ as “the Word of God”.

If our approach to the LXX is governed by our perspective (as in B.A.S.F.) on inspiration, then the LXX should be treated as one would treat any Bible translation. Its merits would be determined through comparative linguistic examination, and any theological predilection(s) of the translators advertised, or detected, taken into account. If we did not consult the Septuagint there would be no loss: after all it is only a translation. Contrariwise, if spiritual advantage is to be gained from its use, then this should be established and the current Statement of Faith modified accordingly. As is customary, scriptural passages would be required to incline us to this view about (e.g., English) translations in general, or about the LXX in particular.

Perhaps we should compare any tendency to elevate the LXX with Roman Catholic history. Final acceptance of Jerome’s Vulgate, in a politically provocative historical climate, came with the decree of the Council of Trent. In the papal statement the Septuagint continued to be ranked with inspired (original) texts:

The decree of the Council of Trent on April 8, 1546, was of epoch-making significance for the later history of the Vulgate: it declared the Vulgate, in contrast to the burgeoning variety of new versions, to be the authentic Bible of the Catholic Church “i.e., authoritative in matters of faith and morals, without any implication of rejecting or forbidding either the Septuagint or the original Hebrew text, or in the New Testament the Greek text”.[17]

It is difficult to avoid giving some weight to the possibility that the traditional Roman Catholic view of the Septuagint has influenced the academic establishment on the use of the LXX in the NT. Perhaps we should be alert to the possibility that this influence is more pervasive than we have hitherto realised?

Conclusion

There are many other matters we might add to our discussion of inspiration, quotation and the LXX, not least about the nature of Biblical ‘quotation’. Further research is needed into how the Bible reuses itself (if I may put it that way).[18] At this stage this essay is only a preliminary and programmatic outline of the theological consequences of following the common commentary line that NT writers such as Peter use the LXX.

[1] W. L. Bedwell, “Echoes of the Septuagint” The Christadelphian (May 1996): 179-182.

[2] In February of 2012, Dr John A. L. Lee (Macquarie University, Sydney), gave ‘The Jeremie Septuagint Lecture 2012’ in Cambridge on “The Pentateuch Translators’ Collaboration.” (He is a former Jeremie essay prize winner and his 1970 Cambridge PhD was published as: A Lexical Study of the Septuagint Version of the Pentateuch, Vol. 14 Septuagint and Cognate Studies Series, Scholars Press, 1983). He focused on his specialist and lifetime accrued lexicographer’s perspective on the LXX Pentateuchal translators’ work. His view from lexicographical analysis is that, contrary to the legend of LXX origins, which claims 72 translators (whence 70 = ‘Septuagint’) rendered the Pentateuch into Greek (ca 250 B.C.), the internal textual evidence suggests it could have been just five translators who, as well as collaborating, translated a book each. This may turn the tide towards history since Aristeas’ account of LXX origins, as Tessa Rajak (2009) has described it, is “somewhere between myth and history.”

[3] The scholarly convention is to use the surname in subsequent references to a commentator; no disrespect is intended for the late Bro. Bedwell.

[4] H. A. Whittaker, without informed qualification, propagandises it as “one of the finest helps in Bible study available today” in: Bible Studies – An Anthology (Cannock: Biblia, 1987): section 10.16, 222-226, “The Septuagint Version – how useful is it?”

[5] D. McCalman Turpie, The Old Testament in the New: A contribution to Biblical Criticism and Interpretation (London, 1868). He gives 37 NT quotations out of 275 which show LXX and NT in exclusive alignment. Some give other figures. His work is still cited with approval for its valuable compilation of texts; see, e.g. the comments on Turpie’s contribution in: The Illustrated Bible Dictionary (Inter-Varsity Press 1980): 1312-1313.

[6] A. Rahlfs, Psalmi Cum Odis (1931), 30-32; Septuaginta (Stuttgart, 1935): xxii- xxxi. Also I. L Seeligmann, The Septuagint Version of Isaiah: A discussion of its problems (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1948): 24-30. C. Stanley, Paul’s Citation Technique (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 52 (see also n. 61); 87-88; 166 (see ‘B’); 185, n. 4, and 254, n.10.

[7] The LXX calls Yahweh (or LXX uses kurios [sic]) ‘the devil’ (diabolos) in 2 Reigns [2 Sam.]24:1 = Para l. A. [1Chron.] 21:1. Not a version to be recommended, surely! The case of transposing the Hebrew ‘satan’ for the Greek ‘devil’ reads as a misunderstood application of the relation of ‘devil’ and ‘satan’ found in the NT (in which not every ‘satan’ is a/the ‘devil’).

[8] J. A. Fitzmyer, A Wandering Aramean: Collected Aramaic Essays (Atlanta: JBL Monograph Series No. 25; Scholars Press, 1979), 121, “Moreover it seems clear that the widespread use of kurios in the so-called LXX manuscripts dating from Christian times is to be attributed to the habits of Christian scribes. Indeed, the widespread use may well have been influenced by the use of kurios for Yahweh in the NT itself…As far as I know, there is no earlier dated manuscript [than A.D. ±200] of the so-called LXX which uses kurios for Yahweh” (Fitzmyer’s italics); see also his n. 44 & n.51, 138-9. On this matter see J. W. Adey “Is Hebrews 10:5’s ‘body’ Language from the Septuagint?” CeJBI 1/4. (Oct 2007): Supplement.

[9] See (p. 34, n. 1), above.

[10] Acts 17:28 from Arastus, or Cleanthes; Tit 1:12 from Callimachus. Some say 1 Cor 15:33 is from Menader, but no mention is made of this being from a non-Biblical source.

[11] T. S. Green, A Treatise on the Grammar of New Testament Dialect (London: Samuel Bagster & Sons, 1842), 6.

[12] C. Stanley, Paul’s Citation Technique (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992): 67- 69; 109, n. 76.

[13] J. R. Michaels, 1 Peter (Word Biblical Commentary 49; Waco, TX: Word Books 1988), 104.

[14] L. Greenspoon, “The use and abuse of the term ‘LXX’ and related terminology in recent scholarship,” in BIOSCS 20 (1987): 21-29.

[15] Stanley, Paul’s Citation Technique, 49.

[16] Translation can apply to an original text (NT) quoting an original text (MT), or to the NT representing in Greek what Jesus and others may have spoken in Hebrew.

[17] Cited in E. Wurthwein, The Text of the Old Testament (London: SCM Press, 1979), 94.

[18] For my own preliminary contribution to this area, see: J. W. Adey, “Complementary Difference: Why New Testament quotations often differ from their Old Testament source”, Christadelphian EJournal of Biblical Interpretation 5/1 (Jan-Mar 2011): 10-27.