Introduction

The Use of ‘leopard’ stretches from Genesis to the Revelation in a narrow theme involving falsely deified men in enchanting political and religious systems. Preaching and prophetic connections run across lands and cultures to show a united devilish concept which, although varying in detail, emerges periodically to threaten true interpretation of God.

Nimrod’s meaning

The name Nimrod comes from two words. N-m-r is the stem for ‘leopard’ in the Old Testament; and the Ebla tablets support this same sense, and so attest to a 3rd millennium B.C. usage for ‘leopard’. (The mound on which the Ebla empire was centered Tel Mardikh reflects in its name the Akkadian form for ‘Nimrod’: ‘Mardikh’, related to the later ‘Marduk’ and Merodach. Marduk was supposedly the son of God (the god Enlil) who as divine king breaks bread with men who worship the moon (Ur). No doubt Abraham, living at the time of these myths, would contrast his leaving Ur and partaking of Melchizedek’s bread with their pagan counterpart.) The second aspect of ‘Nimrod’ is the remaining ‘d’; this is taken from the Sumerian word for ‘god’ (dinger represented by a star-sign). In this way ‘Nimrod’ reflects the idea of a deified leopard, ‘made flesh’ in the man Nimrod. Clearly this had its centre in the cult of hunting and the attached ritual: “He was a mighty hunter faced against Yahweh” (Gen. 10:9; ‘faced against’ accurately renders the Hebrew lpny, for which the AV has the figurative “before”).

Spotting the leopard

Jeremiah indicates a detail of later form of this cult: “Can the Ethiopian change his skin, or the leopard his spots?” (Jer. 13:23). Of course, “Ethiopia” translates the Hebrew Cush. Cush was the father of Nimrod, a genealogy which Genesis places immediately before Nimrod’s hunting prowess (Gen. 10:8). Like father like son: Nimrod had his father’s skin, and was a leopard. This has its matching presence in the Near Eastern cults, which had also spread to Ethiopia from where leopards were supplied for ritual hunting and sport (this source was used later by the Parthians and earlier by Asia Minor). Jeremiah presents the leopard symbolism not only as a religious indictment, but also as an apt political description of the nations thus represented.

The foregoing mixture of the political and the mythical in society has its direct treatment in Isaiah 47. In Isaiah 47:9 the word “enchantments” is the same stem as the term translated “spots” in Jeremiah 13:23. It is not the standard word for ‘spots’, but a rare special designation whose origin identifies with magic and idolatry. This fits in with the leopard: the spots are characteristic typical marks uniting the whore with her ‘deified’ offspring (so the same Hebrew word is used for “fellows” of an idol in Isaiah 44:11). All these senses are the inverted antithesis of the true Biblical symbolism of marriage and union with God (as with “companion” in Malachi 2:14, and “coupling” in Exodus 26:4, where the Hebrew stem is the same as above). The Babylonian whore sits not as a confessed widow in the city Nimrod built (Gen. 10:10), yet God states: “But these two things shall come to thee in a moment in one day . . . for the great abundance of thine enchantments” (Isa. 47:9). (Parts of these expressions are quoted in Revelation 18:1,7,8. Here the leopard has its final hunt.)

So from this we see how apt it was that Nimrod—the head of whose kingdom was Babylon (Gen. 10:10) should share his typical spots with the Babylonian whore. This reflects the choice of the leopard in Daniel 7 and Revelation 13. But in these passages the leopard appears to stand for Greece and Greek influences. Why?

Nimrod and Dionysus

In early Greek sources Dionysus is a god which originates in the east. Euripides’s Bacchae (a tragedy not performed until just after his death in 405 B.C.) is centred on the coming of Dionysus to Greece from the east; this draws from myths ancient at the time Euripides wrote. In Minoan Linear A, about the time of Abraham, the name Dionysus means ‘The Son of God’; and in the Bacchae Dionysus’s supposed divine nature is called into question. ( Scholars variously claim that the Bacchae condemns or glorifies Dionysus. But it seems that the author intentionally offers both aspects.)

However, within this framework the parallels with Nimrod are direct: Dionysus comes from the east with a procession of leopards; and the Bacchae presents Dionysus in a leopard skin and head-dress. Dionysus is the main element in a hunter-cult which concentrates on ritual hunting and the alleged divinity of the deity. And there is an insidious feminine aspect to Dionysus which matches the Babylonian whore, as well as the Egyptian parallel development of the hunter

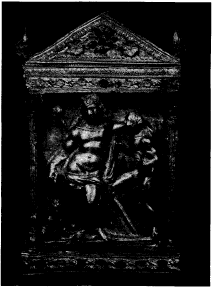

Dionysus is here drunk with ecstasy, supported by a satyr, with a young leopard on symbolic guard. The ceremonial staff behind him is the emblem of Dionysus performing as the booze god (Bacchus). The whole scene is set in a model of a cult temple to memorialise the country cult of dedication involving drunks and fornication. In this way the picture is parallel with the Old Testament ‘grove’, with Baal and Ashtaroth. This adds to the role of the satyr part goat, part man: this was also an Old Testament period devil mentioned in the Bible. (Due acknowledgement to the Athens National Museum.)

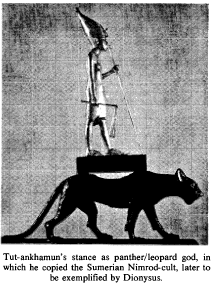

man-god. (This is illustrated in Tut-ankhamun’s hermaphrodite statue astride the ritual leopard/ panther, which reflects the same cultic associations as Dionysus and Nimrod. In most Near Eastern languages, including many Indian, the leopard and panther are indicated by a single term1) For example, Dionysus’s women disciples are said to manifest this god (using the same root term phaneros as 2 Corinthians 4:2, cf. v.4; here the New Testament is attacking false god-manifestation) as they ritually tear one of their sons apart,2 while yet just previously having breast-fed animals which are also torn limb from limb. These phenomena were specifically absorbed into Euripides’s tragedy from cultic practice; the Dionysiac cult also relied heavily on sexual orgy and drug-induced ecstatic dances, not unlike some current vogues in pop-art and ballet From comparisons with early Near Eastern tablets it is likely that the Dionysiac cult matched the Nimrod cult in detail. In this perspective we can appreciate that early BabyIonian mythology had been transported to Greece. Thebes in Greece was a centre for Dionysus, as were Delphi, Eleusis and Athens; Thebes where in recent excavations Babylonian tablets have been found from before the time of the Exodus.3

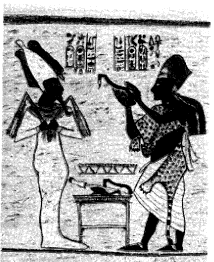

Doris Collett made this sketch of an unphotographable relief in which a sem-high priest wears the magical leopard skin characteristic of his office. The relief exists in Tut-ankhamun’s tomb over the place where his sarcophagus was found. The priest ministers to the dead pharaoh as though he is the incarnation of his god. (Thanks are due to the above artist for permission to reproduce this sketch.)

The Greek leopard

Much was made by the ancients of Alexander’s similarity to Dionysus, as he sped through the Middle East to an early death through too much drink. (Bacchus the god of wine had not protected him.) Yet Alexander was merely conforming to a pattern of cultural origins laid centuries before by his ancestors. The drunken mythology of spiritual fornication had oozed into Greece’s foundations soon after the time of Nimrod. Dionysus is not to be discarded as a minor eccentric mythology; by the ancients and scholars the deity has been acknowledged as the main model for the dramatic centrepiece which is Greek culture: the tragedy of the Bacchae. In the relevant sense Dionysus was Greece. This is a sickness which infected the man of Europe, and especially England; a ‘divine’ ambiguous leopard with unchanging spots of enchantment.

Therefore it is appropriate that the leopard should perform as the symbol, first, for Greece in the prophecy of Daniel; and, secondly, that the leopard should properly map the mainstream Christian religion as pagan cult and political animal in the carnival of symbols celebrated in Revelation 13.4

References

- Hence the late-fifth-century A.D. writer Nonnos, in the late phase of literary decay of writing about Dionysus (in the Dionysiaca XIV), has a panther with spots.

- For a parallel with this and 2 Kings 2:24 see the article “Animals of the Mind”, The Testimony, October 1984, p. 305, section A bear market.

- It is probable that both sea and overland routes brought the leopard cult to For the latter there is evidence in the site at Catal Huyuk in Turkey, where a leopard cult was developed in rock caverns with carvings of leopards and people dressed as leopards in ritual hunt context (see J. Mellart catal Hayilk (London, 1967)).

- It is interesting that the god Dionysus had a near-namesake to whom Paul preached (Acts 17:34); Dionysius (both names were sometimes written in the same way) accepted the gospel in a city and opposite the cult centre where Euripides had himself been shunned for his criticism of Dionysus. Paul’s earlier condemnation of the Athenians as devil-fearers had its correct terminus in his conversion of Dionysius from the devil to Christ.