One feature of recurring interest in the study of the Bible is the way it illustrates the mystical value which the ancient nations attached to numbers. A well known example of this kind is recorded in the last verse of Rev. 13, where the mention of “six hundred three score and six, the number of the beast,” has provided a problem for expositors ever since the words were written. The most striking illustration, however, is the frequency with which the number seven is used with a significance other than that of its numerical value. Seven is associated with the idea of perfection or completion, probably because of the divine marking off of time in the beginning by the six days of creative action and the seventh of rest. Some such significance is evident. The clean animals sent into the ark by sevens, the seven years Jacob served for each of his waves, the seven branched lamp in the Tabernacle, the furnace of Nebuchadnezzar made seven times hotter, all these indicate this peculiarity. Prophetic symbolism, from the seven fat kine of Pharaoh,s dream to the seven vials full of the seven last plagues of John’s Revelation, is enriched by this same mystical usage.

Occasionally the significance appears when the number is introduced in apparently quite an accidental manner. In this category can be placed the epistles which the Apostle Paul wrote to ecclesias, or communities of called out ones, men and women called out from their worldly associations by their attachment to the Gospel of Christ. Paul wrote to seven of these churches. If the significant sense of this number be considered, it suggests that his presentation of the Gospel was perfect in its development of the whole counsel of God, which he did not shun to declare to all men. Or, the seven churches may be taken as a complete representation of all classes of men to whom the Gospel makes its appeal. Thus the use of the mystic number conveys the idea that the writings of the Apostle to the Gentiles present a complete system of instruction in righteousness, that the man of God may be perfectly prepared for the coming Kingdom of Christ.

The Churches written to were, of course, those at Rome, Corinth, Galatia, Ephesus, Philippi, Colosse, and Thessalonica. This is the order in which the epistles are arranged, and though it is not by any means the order in which they were written, they have always followed each other in this manner in the collection of books which make up the New Testament. The relative dates of their composition are thus missed; but more is gained than lost, for the order in which they have been arranged brings out a relationship between the epistles which is both interesting and instructive.

In referring to the Scriptures the apostle stated that “they were profitable for doctrine, reproof, correction and instruction in righteousness,” II. Tim. 3, 16. These qualities apply also to his own ecclesial letters. All give instruction in righteousness, but some are more doctrinal than others, and some are more conspicuous than others by their admonitory tone.

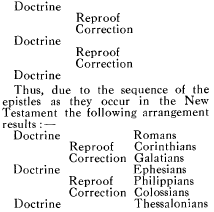

The seven epistles can be subdivided into three and four embodying these distinctions, three being doctrinal and four conveying reproof and correction. This subdivision is further arranged in this order.

In this order they bear a relationship to each other which is not the less interesting because it was quite unpremeditated. A certain standard of teaching was set up in Romans. The Corinthians were reproved, and the Galatians corrected because that standard was being obscured in those communities. So with the next set of Epistles. Ephesians sets up a doctrinal standard which the Philippians were reproved and the Colossians corrected for not observing. The doctrinal letter to the Thessalonians closes the sequence.

Distinction is made between reproof and correction, because the declension from the doctrinal standard in the one case was in conduct, while in the other it was in belief.

The three doctrinal epistles demonstrate a progressive development in the presentation of the Gospel of God. Without attempting anything more at present than a very brief review of these letters, it can be stated that the one to the Romans forms the foundation of the Gospel teaching, the ABC of Christian knowledge. It depicts the inherent evil of human nature, as the consequence of the entrance of sin into the world by the transgression of the parents of our race. Sin reigns as universal tyrant, faithfully paying wages to his servants, and “the wages of sin is death.” The divinely given law only made sin more manifest because none were able to keep it perfectly, so the Jew had no grounds for boasting against the Gentile. God love was manifested to all men in sending His Son in the likeness of sinful flesh to undo by his obedience the evil brought about by Adam’s disobedience. Jesus is set forth as a propitiation declaring the righteousness of God in the remission of sins that are past, on the principle of faith in the shed blood of Christ. This faith is manifested by baptism into Christ,s death. This act severs allegiance to the tyrant Sin, and a new life of service to God is entered upon with the promise of immortality to those who ‘henceforth walk not after the flesh but after the spirit.”

Justification by faith is the great principle of this letter. The Epistle to the Ephesians takes up the teaching from this point, and carries forward the idea of the relationship between the believer and his Lord. He is described as sitting in heavenly places in Christ, being brought out of a condition of ignorance and hopelessness to one of unity and peace with God. He puts on the new man which is created in righteousness and holiness. So he is sanctified to the service of the Lord.

The successful issue of this service leads to the glorification in Christ which is the burden of the epistle to the Thessalonians. The Apostle himself gloried in the church because of its patience and faith. He commended it to the rest that would be received when Christ, in the glory of His power, would come to be glorified in His saints.