Introduction

The Biblical drama of Job has proven a long-standing enigma. A faithful disciple is seemingly tortured at the hands of his God, apparently so that the Deity might win a barter. It sounds like the most deplorable of Greek myths, yet the drama rests within the Bible, the central text of Christianity! Reaction to this Old Testament (OT) book has generated many varied emotions, to say the least. Many Christians simply avoid the book altogether, or conclude that the God of the Old and New Testament (NT) are very different.

The central feature of my interpretation, as the title of this article implies, is that one can actually present the behavior of God in a praiseworthy light throughout the Joban drama, without distorting the text, introducing extraneous ideas, or minimizing Job’s suffering. This approach is distinctively different to other expositions which, perhaps in somewhat defensive mindset, tend to either conclude that God’s restoration of Job is sufficient to recompense for His destruction of him, or that the Joban drama teaches that we must not question God. This latter conclusion reminds me of the generic defense lawyer who does not permit the questioning of his client, quite possibly because he believes that any close questioning might readily expose his client’s guilt!

Synopsis of the Biblical Drama of Job

Prologue (chapters 1-2, prose): God invites a character termed “the Satan”[1] to consider the piety of his servant Job. The Satan counters that God has failed to realize Job is only pious because he is well blessed in riches and, were he deprived, he would curse God. God allows the Satan’s demands to be met and God Himself destroys Job’s fortunes, family and ultimately health. Yet Job does not curse God; the Satan loses the barter.

Debate (chapters 3-31, poetry): Job’s three friends, Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar come to sympathize but, ultimately, they chastise Job. A debate ensues, where each speaker attacks Job in turn, calling upon him to acknowledge the sins they believe must have triggered his destruction, and Job replies in self-defense. In all fourteen speeches and rebuttals are voiced, with the debate growing ever more heated and culminating in lengthy speeches from Job appealing to God to appear so that his (Job’s) righteousness can be revealed.

Intervention (chapters 32-41, poetry): Instead, a young witness, Elihu, speaks out. He too is critical of Job, yet limits his criticism to Job’s recent words, not lifestyle, all the while defending God as righteous.

Then God speaks (His longest speeches in all scripture!). He first presents a tour of creation, focusing especially on wild animals, observing that He can control them where Job cannot. When Job briefly responds, God rebukes him and launches a second speech focused wholly on His ability to control two beasts whose descriptions seem other-worldly. Job’s latter response states he has ‘seen God’ and avers a new life direction.

Epilogue (chapter 42, prose): God rebukes the three friends for not speaking correctly about Him; praises Job for succeeding in that regard; and directs Job to intercede in prayer for his friends for God to forgive them. God then restores Job: he receives double of his previous blessings yet, while he receives twice as many flocks and herds as previously, he is only blessed to receive as many children as before.

Understandably, the plotline forms a mystery – arguably several mysteries!

Theme: To Speak Well of God

The underlying theme of the Joban drama is how one speaks about God. ‘Who God is’ is the most prevalent theme within the drama. A further subtle indicator of this theme is that the first and last spoken words of the drama concern how one speaks about God, with the entire drama sandwiched between. The first words spoken are by Job: he sacrifices for his children in case they have spoken ill of his God. Similarly the last spoken words, spoken by God, chastise Eliphaz and his two friends for not speaking well of God where Job did. (Job’s sacrificing for his children also showed he had chosen for himself the lifestyle of a priest.) The drama of Job vicariously challenges each of us similarly as we witness his destruction. Job, from the crumpled carnage of his life, still manages to speak well of his God. But will we?

Enter Satan

The identification of Satan is critical to any interpretation of the unfolding drama. I propose[2] that the Satan throughout the Bible is a metaphorical character who represents human pride—and in this specific drama of Job the Satan is the distilled pride of the three friends. This proposal is based on a number of observations (and the assumption that the canon of scripture communicates a consistent message):

- The word ‘Satan’ is a Hebrew word meaning ‘opponent’ and is referenced with the definite article (i.e. The Satan). This suggests ‘the Satan’ may be a metaphorical character, not a proper name.

- The natural reading of the prologue indicates that the ‘opponent’ is the opponent of God.

- While many take the Satan to be an angel, either benign or malign, Peter’s NT writing excludes this possibility; revealing angels do not slander righteous men (as the Satan does to Job).

- All other scriptures indicate that the opponent of God is invariably the stubborn, proud heart of man (e.g. Genesis 6; Jeremiah 17; Mark 7).

- The Satan is stupid! The entire basis of the Satan’s argument is that he is cleverer than God and has observed something God has missed. This characteristic arrogance points strongly at human pride as the source.

- The scriptural template of God interacting with Satan follows three generic points: 1) God speaks a truth; 2) Satan counters with an untruth, which forms an accusation against a righteous man; and 3) God rebukes the Satan. (E.g. Genesis 2-3 & Revelation 12; Matthew 16; Ezra 1-4 & Zechariah 3). This template is consistently fulfilled in Job if we understand the Satan as the pride of the three friends, because their untruths concerning God’s character form accusations against righteous Job and their pride-filled rhetoric is rebuked by God at the end.

I interpret the ‘conversation’ between God and the Satan as a literary device. Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar “present themselves before the Lord”, and they see Job in the assembly and, because of his wealth, the sight of him causes their blood to boil with the sense of perceived injustice. God hears the slanderous evaluations of their hearts as clearly as if they had been words shouted aloud. His response is recorded in the drama’s text but, I suggest, God’s words are not heard by the three friends. In other words, the Satan is unaware that he is in ‘conversation’ with God, even as the conversation proceeds. This satisfies the essential requirement that the three friends have no knowledge of the events of the prologue; else the subsequent debate about why Job is suffering would not occur.

I understand the ‘conversation’ in Job as a poetic recapitulation of the events where God responds to the thoughts he sees in the hearts of prideful men. This literary device is an attractive way to reveal to the reader how God works in human lives, bringing situations we need to experience to bear, as He works to fashion more godly disciples and gently chafe away the rough edges that do not reflect Him.

The affliction brought upon Job is explained similarly. The friends see Job and think: “How could God allow this injustice? Doesn’t He see that the only reason Job is pious is because of all the material blessings He has given him?” God ‘replies’—though the three men never hear the words—”I see what you’re thinking. You think that if Job loses his material possessions he’ll curse Me. I have something to teach you. I’ll empower your wicked thoughts and act on them. I’ll bring destruction on Job, just as your jealousy wants, and you will see, through the perseverance of my servant, the type of God I am and what I am working to ultimately achieve”. This demonstrates God brought the affliction, but the Satan is to blame for the affliction, both of which details are specified in the text.

The all-important consequence of this interpretation of the Satan is that it dramatically changes our appreciation of who God is. By peeking to the end of the story we see that the three friends are brought to salvation by what happens to Job, so we are enabled to realize that the reason God entered the ‘barter’ with the Satan was because He had a specific intent of bringing salvation, even to those infected by that Satan! This is of critical importance, as this interpretation demonstrates the love of God, to save even those under the influence of the Satan (pride), more powerfully than any other interpretation (cf. John 3:16).

The Wilderness Journey

Investigating the genealogies of the characters reveals that Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar are all children of Abraham, while Job is likely a Gentile. This sets the precedent that there are children of Abraham self-righteously and falsely accusing a righteous man whose father’s lineage did not trace through Abraham; just as the Pharisees would later do to Jesus of Nazareth. The implied message, even back in OT times, is that to be a child of God is determined by one’s lifestyle, not one’s lineage.

Job’s genealogy is blatantly obscured in the drama. He is never listed with his lineage and, reinforcing the contrast, Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite and Zophar the Naamathite are never listed without theirs.

Researching the ‘when and where’ places the drama during the wilderness wanderings of Israel under Moses, both geographically and chronologically. The land of Uz is in the desert south of the Promised Land. As for timing, comparisons between Job’s statements and the prophet Isaiah show Job speaks about the destruction of Egypt in the Red Sea during the Israelite Exodus. This implies that Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar, children of Abraham, are part of the wandering multitude.

This timing and geography influences the spiritual vista. Israel is at their lowest spiritual ebb. It has been ~500 years since Jacob (Israel) left Beth-el (house of God); and Joshua (Hebrew: Jesus) is yet to lead them back. So we can understand, though not excuse, the moral emptiness of the three friends’ arguments, from the backdrop of the literal and spiritual homelessness of the people.

The scene of the drama is the wilderness; the interplay that the Satan will clash head to head with the Righteous Man there. An important theme is emerging.

Satan in the Wilderness: The Debate

Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar’s speeches reveal they believe in the doctrine of retribution: a simplistic tenet that states anyone who suffers does so because God is punishing them for their sins. Their speeches ultimately blossom in demanding Job to confess the sins they believe he must have committed. As each speaker takes the podium he attacks Job more determinedly than the preceding one and likewise Job feels driven to defend himself ever more stridently. Job succeeds in rebutting their false accusations, so the three friends lose the debate. But Job’s victory is pyrrhic: he is now as haughty as the friends. He denounces God’s treatment of him and effectively subpoenas God, demanding an audience with Him so he can display his own righteousness.

God will now not speak to Job, to protect him from misunderstanding that the Creator is answerable to His Creation at any time the latter demands.

The winner of the debate is, curiously, the Satan; because human pride is now dominant throughout all four speakers. Satan struggles against a righteous man in the wilderness – and Satan wins! This gives a fascinating education to all disciples who likewise struggle in their own wilderness: righteous conduct will not defeat the Satan.

My Messenger

The Debate’s finale requires that another character arrive, to vacate the subpoena Job has unwisely issued, freeing Job so he can hear from God without misunderstanding that God was required to obey his demands.

Thus, the entrance of Elihu, which happens at this point, should no longer be thought erratic or inexplicable, as it is in most expositor’s works. I believe the evidence shows Elihu is a good man whose character and conduct are dramatically opposed to the three friends’. I propose the following reasons for this view:

- Elihu calls for God to be praised; the three friends remain silent on this matter. The importance of this distinction is amplified when seeing ‘Speaking Well of God’ as a central, underlying thesis to the drama.

- Elihu ascribes his wisdom to God; the three friends claim (ironically accurately) their wisdom is their own.

- Elihu explicitly states his desire is that Job be found innocent; the friends have already pronounced Job guilty.

- Elihu is not criticized by God; the three friends are.

I hypothesize Elihu should be understood as a type of John the Baptist who is preparing the way for the Word of God’s arrival. Comparisons between Elihu and John show these distinctive parameters:

- Introducing the arrival of the Word of God.

- Having a purpose of ‘straightening the way’, as Isaiah states it: i.e. correcting misperceptions in the audience, so that when the Word of God comes the audience will be best placed to understand Him. Specifically, Elihu flatly disagrees with the three friends’ arguments and also corrects Job’s few errors, elucidating that God is present, does answer prayer and does not pervert justice. This is Elihu’s work, to vacate Job’s subpoena, allowing Job to hear from God.

- Anticipating the themes of the Word of God even to the extent of explicitly voicing them. John the Baptist correctly anticipates the theme of repentance in preparation for the kingdom of heaven. Elihu specifically comments on God’s authority via His thundering voice, that He controls the elements of the weather and that His principal task is to deliver man from pride, all three of which correctly anticipate God’s revelations to Job.

- Fading away when their job is done, as is the signature of the herald. Elihu’s disappearance, which perplexes most expositors, becomes understandable using John the Baptist’s explanation of his own role: “He [the one I introduce] must increase and I must decrease”.

God Speaks

Almost every expositor suggests either that God does not answer Job’s cries for help, or that God’s speeches are designed to communicate solely His Supremacy and that Job has no right to question Him. I contend instead God answers Job’s cries for help; and in a style which also reveals truths Job had not appreciated.

The divine point, of which Job is unaware, is that Job is now infected with pride—caught in the jaws of the Satan. God sees this Satan as a rampaging Wild Beast which He will later label Leviathan. God’s desire is to save Job; that is His character. It is with compassion for Job’s situation that He asks Job in His first speech: “Are you as good as I am at controlling wild beasts, Job?”

Job is dismayed. His perspective is very different. So far he sees he has been cursed, evidently from God and then wrongly denounced by the hapless moralizing of his proud friends. He has hollered to the heavens for deliverance and received no answer. And now the Lord he has been seeking has finally appeared He seems to be sneering at Job for his inability to control the animal kingdom! Disconsolate, having misunderstood his Father’s currently obscured message, Job sulkily replies that he is aware of his inferiority.

But God is aware that His excellent disciple can hear the Word of God, so He speaks again. He continues the same theme, yet transitions from the natural creation to the spiritual creation, to reveal: “So how can you control THE Beast, Job? The rampaging beast that brings every man down? Do you recognize this beast? Let me describe him to you. Have you seen him anywhere recently?” And such is the resonance between the godly disciple Job and God’s Mind that, even on first hearing, Job understands!! Job realizes that the Beast Leviathan is the Satan who is human pride, whom he has been unsuccessfully wrestling. He sees only the Word of God can defeat this Beast. Job’s restoration, and the salvation of his three friends held by the Satan, can now begin in earnest.

God has presented the Beast of human pride in His second speech using two visions (Behemoth and Leviathan) which have the same interpretation. This mirrors the (recent) time of the Pharaoh when God sent two visions with the same meaning. The purpose, Joseph explained, was to communicate that God’s decision is certain and He will act soon. This hints that God’s restraint of the Satan will certainly occur, and soon; lending additional credence to seeing the three friends associated with the Satan, who are rebuked in the very next chapter.

The fact that the Satan can only be defeated by the Word of God has fascinating implications for the NT gospels. It teaches that Jesus, who struggles against the (same) Satan in the Wilderness— and wins!—does not win because he is a righteous man. The Joban drama teaches Jesus wins because he is the Word of God, a message in perfect harmony with John’s Gospel’s presentation of him. In fact, Jesus may have learned this from reading Job.

Importantly we see that God’s speeches are insightful, on topic and, above all, helpful to the cries for assistance from the disciple He loves. Did we really expect any different?

Salvation

Job is utilized by God to act as priest for his three friends, quite possibly because Job had chosen a priestly life, as we are shown in the prologue. Since Job is not descended from Levi, it must be the spiritual priesthood of Melchizedek into which God has enrolled him. The NT letter to the Hebrews explains the two identifiers of Melchizedek’s order: 1) they learn obedience through suffering; and 2) they have “neither father nor mother”, appearing essentially ‘out of the blue’. This latter feature explains why Job’s genealogy is deliberately obscured in the drama: to represent him as a priest in Melchizedek’s order.

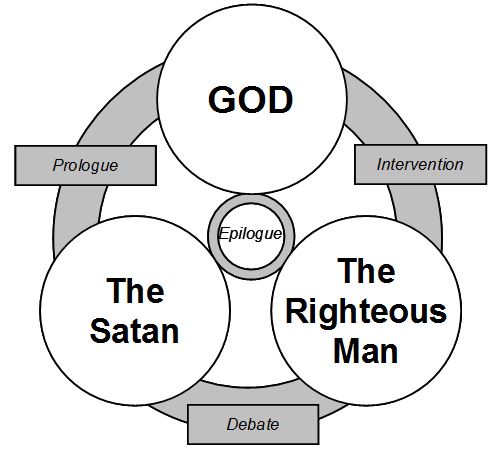

Figure 1: The Book of Job. Circles represent the characters, grey bars the interfaces between them.

Job’s ‘double-portion’ blessing seems only to be realized in receiving twice as many flocks and herds, yet not children. The beauty and subtlety of what God does here is profound. The only way Job can have fourteen sons and six daughters, twice what he had before, is if the original seven sons and three daughters can, in some way, be considered to be alive, in a way in which the equally deceased animals are not. I believe God is communicating the hope of resurrection to Job! And God sends this message in His characteristic way, via a very subtle play of numbers of flocks, herds and children: a message medium so gentle it will not even be noticed by any but the most careful listener. But Job is an extremely careful listener to God’s words, as the drama has shown. This is a unique and amazing promise given to a unique and amazing man. Most importantly of all, it enables us to speak well of God, as it powerfully illustrates the unfailing love our Father willingly displays towards His children, which flowers in the ultimate hope of resurrection for all His children.

The drama has shown that the suffering of a righteous man has brought salvation to unrighteous men. In this statement alone we can see both a wonderful reason for that suffering—to save lives—and also whom Job foreshadows: the Christ. For if the suffering of one righteous man can bring salvation to three of his friends, how much more can the suffering of The Righteous Man bring redemption to all who will be his friend?

To Speak Well of God

The Joban drama is delightfully simple: just three characters and the all-too-revealing interactions deriving from their inherent natures. God is laying out before us the three fundamental forces in the spiritual universe: God; Good; and Evil and using the drama to teach us their true nature. The characters are:

- God (not counting his ‘armor-bearer’ Elihu as a separate character in his own right, which is appropriate).

- The Satan, Leviathan, human pride, the second most powerful force in the universe, who is in essential opposition to God. He is manifest in the triumvirate form of the three friends of Job; (yet the three friends are victims of Leviathan as much as they are unwitting promulgators of him).

- Job, the Righteous Man, who attempted to wrestle with the Satan; and through whose intense suffering God was able to free the three friends trapped in their own pride.

The drama can be summarized in four simple movements, where God sequentially steps through all four interactions that can exist in the spiritual universe (see Figure 1).

- Prologue: God interacts with the Satan. The subject is how the Righteous Man, Job, behaves.

- Debate: The Satan interacts with the Righteous Man. The subject is how God behaves.

- Intervention: God interacts with the Righteous Man (initially through one sent before to straighten the way and then directly). The subject is how the Satan, Leviathan, behaves.

- Epilogue: All three parties collide and the conclusion of the matter is revealed. God speaks concerning all parties. The Righteous Man speaks concerning God and himself. The Satan is left with nothing to say. I suspect it will also be this way at the ultimate conclusion, at the end of days.

Woven amid the dramatic interactions is the theme itself: “theology” (Greek: Theos = God; Logos = word), i.e. the words that a man, whether he in is opposition to God or in resonance with Him, i.e. whether he is satanic or righteous, will speak about his God.

Whence then Job’s suffering? Ironically, it was a consequence of sin, just as the three friends had said all along. But not his sin, as they had wrongly supposed: theirs—the intractable pride that kept them from union with their God. But because God loved them, and saw the persevering faith of His servant Job, He devised a plan by which their pride would be brought into such sharp relief that they would be able at last to recognize their error, repent and find grace; provided their priest was willing to intercede for them. And what an immense degree of suffering Job had to bear for this to happen! Such is the degree of damage human pride inflicts upon the world. Yet now that we can see the true source of the suffering—human pride—God is justified even as Job suffers.

It is the drama of Job which, perhaps in total opposite to its surface appearance, has revealed the true degree of care God has for all men, in that He attempts to bring salvation to everyone. Perhaps it is no wonder the drama is introduced with God’s curious invitation, aimed at any who truly want to know Him: Have you considered my servant Job?

[1] [ED JA] Translation note (and see n. 2): this use of “the Satan” is a mixed mode of presentation: part translation (‘the’), and part transliteration (capitalised ‘Satan’). Translations, ancient and modern, are variable when representing the Hebrew ‘S†n’ – !jf – family of terms, and in some cases advertise the imposition of diachronic, or other, presuppositions. The approach found recently in R. E. Stokes, “The Devil Made David Do it . . . Or Did He? The Nature, Identity, and Literary Origins of the Satan in 1 Chron 21:1” JBL 128 (2009): 91-106, connects, albeit in a preliminary way, with some aspects of the discussion needed.

[2] [ED AP/JA] This proposal is one point of view in the Christadelphian community. However, there are many issues to investigate and address, such as, the exact linguistics of the term and whether “(the) Satan” is a metaphor in all biblical texts, exactly what type of metaphor, and how other levels of meaning are present in some texts, and how all the texts cohere under tradition-historical umbrella, is a subject that it is hoped will be addressed in future articles.