Introduction

Previous articles on the Fourth Gospel (4G) suggested that the Gospel was written to the Diaspora at Ephesus and discovered links between the 4G and Luke-Acts.[1] Luke is regarded as Paul’s companion and biographer; therefore his employment of underlying Johannine sources helps in establishing the early provenance of the Fourth Gospel – before the segregation of a distinct “Christian” ecclesia at Ephesus (founded by Paul).

The following article will attempt to demonstrate that the Epistle to the Hebrews was written to the same audience (Diaspora Jews at Ephesus), probably after the death of Paul. Hebrews shows the same concerns about baptism as the 4G; however, in Hebrews the situation is in danger of degenerating into outright apostasy.

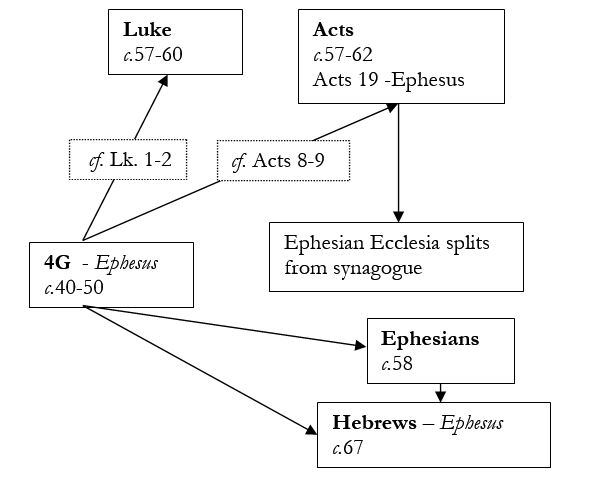

The relationship between the books might be represented as follows:[2]

The Doctrine of Baptisms

The unusual plural phrase, “of the doctrine of baptisms” (baptismw/n didach/j), is listed in Heb 6:2 among the rudimentary teachings of Christ. How then are we to understand such baptisms? Is this contrasting the baptism of John and Christian baptism? J. D. G. Dunn believes that those addressed are most probably converts from Judaism:

The initial preaching to them having taken up what was valid in their old belief. This is the best explanation of the non-(specifically)-Christian list of six points: they describe an area of overlap between Judaism and Christianity in terms common to both…[3]

R. Beasley-Murray states,

Since the plural ‘baptisms’ is so unusual in the New Testament, we may safely set aside the view that repeated immersions are thereby intended. The employment of baptismo,j instead of the usual ba,ptisma confirms what in any case most naturally occurs to the reader, that the writer implies a contrast between Christian baptism and other religious ‘washings’. The term is wide enough to include the ritual washings of the Old Testament and every kind of baptism by initiates known in the writer’s time, including the baptism of John, the baptism practised in the Jordan Valley and by the Dead Sea, Jewish proselyte baptism, and whatever ritual washings existed among the various Mystery Religions.[4]

Previously, we have argued that the baptism of John and Christian baptism were essentially the same. The baptisms in Heb 6:2 are set in the context of “laying again the foundation of repentance from dead works” (Heb 6:1). The foundation of repentance can only refer to the baptism of John, whose baptism of repentance was the cornerstone or founding element of what would become the fully developed Christian baptism. We suppose that the letter’s warning against apostasy concerned those who had experienced the baptism of John and had consequently received the Spirit through the laying on of hands (cf. Heb 6:2) or, who had been re-baptised (like the disciples of the Baptist found at Ephesus in Acts 19:1-7). They were in danger of drifting back to Judaism. J. A. T. Robinson states that,

…just as disciples of John transferred their allegiance to the Christian church (as John 1 asserts and Acts 18-19 presupposes), so John himself is best explained on the hypothesis (however guardedly stated) that he had perhaps earlier been brought up in the Qumran community, or at any rate that his baptism of repentance is more fully understandable against that background than that of the other contemporary Baptist sects.[5]

This is entirely plausible as the Qumran community also practised lustrations and attached importance to the Isaiah oracles.[6] The Qumran community was hostile towards the Jerusalem priests whom they regarded as evil and impure. The only rituals available to them (outside the Temple cult) were the baths and lustrations practised in the Old Testament. The Qumran covenanters had an eschatological orientation and by applying texts such as Isa 40:3, saw themselves as preparers of the way.

John the Baptist may or may not have grown up, or been influenced by the Qumran community; what is clear, however, is that his baptism was unique. It can be differentiated from the multiple Qumran baptisms in that it was a one off rite, concerned with repentance and manifesting the Messiah, rather than external purity. John’s baptism differentiated itself so substantially from Qumran that it required further probing from the Jerusalem temple elite (John 1:19) – an investigation that would be uncalled for if it was simply an extension of Qumran covenanting. Nevertheless, John’s baptism would readily lend itself to Judaists who attempted to subvert his former disciples back to the ritual purity of the Torah (water pots for purifying the Jews—John 2:6). The lapsed were ‘once enlightened’ and had ‘tasted the heavenly gift’ (Heb 6:4-5).

These last phrases often have exegetes in a quandary,[7] largely due to a failure to recognise the chiastic structure and the correspondence with the 4G:

A who were once enlightened, and have tasted the heavenly gift,

B and have become partakers of the Holy Spirit,

A’ and have tasted the good word of God

B’ and the powers of the age to come.

The ‘power of the age to come’ is obviously synonymous with the ‘Holy Spirit’, which is the eschatological Spirit par excellence. Similarly, the ‘tasting of the heavenly gift’ is synonymous with, ‘tasting the good word of God’ and this experience is equated with ‘enlightenment’. Our suggestion is that the heavenly gift is the bread from heaven, and scholars fail to recognise the Johannine idiom—it speaks of partaking of the bread and wine:

| John | Hebrews |

|---|---|

| 1:26 I (John) baptize with water…. | 1. Foundation of repentance |

|

1:5 The light shines in the darkness…. 1:9 The true Light which gives light…. |

2. Once enlightened |

| 4:10 If you knew the gift of God…. | 4. Tasted the heavenly gift |

| 6:53 Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood…….. | 5. Tasted the good word of God |

| 14:26 But the Helper, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in My name….. | 6. The powers of the age to come |

Common Themes between Hebrews and John

The letter to the Hebrews demonstrates familiarity with many of the themes that interested the Fourth Evangelist.

1) The centrality of the figure of Moses (Heb 3:2f, 5, 16; 7:14; 8:5; 9:19; 11:23f; 12:21: John 1:17, 45; 3:14; 5:45f; 6:32; 7:19, 22f; 8:5; 9:29). This corresponds to the veneration of Moses in Hellenistic Judaism of the Diaspora,[8] which understood Moses as unique because of his unmediated access to the presence of God (cf. John 1:18).

2) The particular contrast between the shadow (type) and true fulfilment is also a typically Johannine mode of idiom (the copy and shadow of the heavenly things (Heb 8:5); true tabernacle (Heb 8:2); copies of the true (Heb 9:24); the true Light (John 1:9); the true bread from heaven (John 6:32); and the true vine (John 15:1)).

3) The nearest NT parallel outside the Johannine Corpus to ‘the Word’ (John 1:1-3) is in Hebrews (Heb 11:3; cf.1:3). Similar to the 4G, Hebrews stresses the superiority of Christ’s ministry; it is no longer John the Baptist who is the forerunner (John 3:28), for Jesus becomes the forerunner of all believers:

Whither the forerunner is for us entered, even Jesus, made an high priest for ever after the order of Melchizidek (Heb 6: 20).

John the Baptist may have been “sent avposte,llw (apostello) before him” (John 3:28), but Jesus was the avpo,stoloj (apostolos) “the Apostle and High Priest of our confession (Heb.3:1). He was not an Aaronic priest like John, but a priest of an entirely different, higher order.

4) Hebrews (like the 4G) is also concerned with differentiating the cultic cleansings of OT ritual with baptismal cleansing representing the sacrifice of Christ. The ashes of the red heifer may have sanctified the unclean person’s flesh, but they did not actually take away sins: “let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, having our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience and our bodies washed with pure water” (Heb 10:22). The parallelism is not antithetic; it is purely rhetorical (cf. Ezek 36:25).

The Ephesus Connection

Several textual details fit an Ephesus location for Hebrews:

1) The incident in Acts 19:13-17, which occurred at Ephesus, anticipates the theme of Hebrews 12—the removal of Mosaic forms of worship. The seven exorcists, the sons of the chief priest Sceva are overcome and flee the house naked and wounded.[9] The Synoptic parallel (Matt 12:43-45) is the Parable of the Wicked Spirit where we read “seven other spirits more evil (ponhro,teroj) than itself…who decide to return to my house from which I came”. The same term, “evil/wicked” (ponhro,teroj), is employed in Acts 19:12, 13, 15, and 16 to contrast the casting out of wicked spirits by Paul with the exorcisms practised by the Jews. The Parable of the Wicked Spirit and the incident in Acts 18 should be seen against the background of John the Baptist, who had come to prepare the ‘house’ for the Passover Lamb (John 1:29), and Jesus who had literally swept the ‘house’ clean in order to remove the ‘leaven’ (John 2:15).[10]

2) The situation within the community described in the letter to the Hebrews (Heb 10:32-34) is one of persecution and difficulty, but not of martyrdom, as Heb 12:4 states that they had “not yet resisted unto blood” in the cause of Christ. It is noteworthy that although they were made a public show (qeatri,zw), “a gazing stock” (KJV), they were not subjected to loss of life. The Greek word signifies “to make a spectacle”, from which we get our word “theatre”. The riot (spectacle) at Ephesus occurred in the magnificent theatre of that city (Acts 19:31). In the past, Jewish converts, including former disciples of the Baptist, had loyally stood by their fellow Christians, but now they had to be reminded of their solidarity (Heb 13:3).

3) The author of Hebrews is also aware of the Pauline epistle to the Ephesians. Similar to Paul, he associates[11] Psalm 110 with Psalm 8 (Heb 1:3, 13, cf. Eph.1:20, 22) and Psalm 8 itself is cited in Heb 2:6b-8a. We may surmise that whereas Ephesians was written to the Gentile element in the ecclesia (Eph.2:11; 3:6-9), Hebrews was directed at the Jewish Diaspora: such expressions as “the fathers” (Heb 1:1), “your fathers” (Heb 3:9), “seed of Abraham” (Heb 2:16) and the language of Heb 13:9-15 is evidence of such an audience.

4) Another recurring theme in Ephesians is that of the “heavenly places” or “heavenly things”— it is used five times in Ephesians (Eph 1:3, 20; 2:6; 3:10; 6:12) and only three times elsewhere. Two of these occurrences are in Hebrews (Heb 8:5; 9:23) and one in John 3:12. This neatly links John, Ephesians and Hebrews.

5) The Pauline themes of “boldness of access”, and “sonship” (Eph 3:12) are also concepts upon which the author to the Hebrews expands (Heb 3:16; 4:16; 10:19, 35). Whereas Paul makes the Ephesians aware of the privilege of being “foreordained unto the adoption as sons through Jesus Christ” (Eph 1:5), the author to the Hebrews reminds them that with sonship comes responsibility and chastisement for wrongdoing (Heb 12:5-6). Paul’s epistle to the Ephesians addresses the tensions caused by the inclusion of Gentiles into the covenant relationship; Hebrews—the problem of Jews reverting to righteousness through legalism. Further thematic links are set out in the following tables:

| Ephesians (Gentile) | Hebrews (Jews) |

|---|---|

|

Saved through faith… not of works that man should glory (2:8). Strangers from the covenants of promise (2:12). No more strangers and sojourners but fellow citizens (2:19). |

Salvation by faith (Hebrews chapter 11). Strangers and pilgrims (11:9, 13). He hath prepared them a city (11:16). |

| 2:14 For He Himself is our peace…. | 7:2 King of Salem, which is king of Peace |

| 2:14 Who hath made both (Jew/Gentile one and brake down the middle wall of partition (between God and man) having abolished in his flesh… | 9:10 By a new and living way which he hath consecrated for us, through the veil, that is to say his flesh… |

| 2:14-15 …The enmity, even the law of commandments contained in ordinances | 10:20 Carnal ordinances, imposed until the time of reformation |

| 1:15 Wherefore I also, after I heard of your faith in the Lord Jesus, and love unto all the saints… | 6:10 God is not unrighteous to forget your work and the love, which ye showed towards his name |

| 1:15-18 ….the eyes of your understanding being enlightened; that ye may know…… | 10:32 …..which after ye were illuminated (enlightened by the spirit)… |

Conclusion

Hebrews was written to an urban community (Heb 13:14) that had links with Timothy and with those “from Italy” (Heb 13:24), a phrase previously used to describe Priscilla and Aquila (Acts 18:2), who had close associations with Ephesus (Acts 18:24-26). The author of Hebrews was familiar with the Pauline circle but this does not necessarily mean that Hebrews was written by Paul (who was probably martyred by now). We conjecture that the epistle was written to Ephesus from somewhere in Asia, where the author, together with Priscilla and Aquila (of Italy) were waiting to be joined by the liberated Timothy (who was imprisoned in Rome?). The cumulative evidence presented so far suggests that the 4G, Hebrews and Ephesians were directed at different elements within the Ephesian community. The 4G was written to the Diaspora Jews before the split with the synagogue; Ephesians was written after the split (when Gentiles were included); and Hebrews was a warning directed at Diaspora Jewish Christians at Ephesus who were drifting back to an apathetic Judaism.

[1] See P. Wyns, “The Destination and Purpose of the Fourth Gospel” and “The Fourth Gospel and Paul” in Christadelphian EJournal of Biblical Interpretation, (Vol. 3, No. 2, 2009).

[2] The dates are culled from J. A. T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (London: SCM Press, 1976), 352. Dates are given as approximations (by no means fixed) in order to establish relationships. For a review, see P. Wyns, “Review: Redating the New Testament” in Christadelphian EJournal of Biblical Interpretation Annual 2007 (eds., A. Perry and P. Wyns; Sunderland: Willow Publications, 2007), 123-126.

[3] J. D. G. Dunn, Baptism in the Holy Spirit (London: SCM Press, 1970), 206.

[4] G. R. Beasley-Murray, Baptism in the New Testament (Biblical and Theological Classics Library: Carlisle: Paternoster, 1997), 243.

[5] J. A. T. Robinson, Priority of John (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985), 172-173.

[6] J. A. T. Robinson, “The Baptism of John and the Qumran Community” in Twelve New Testament Studies (London: SCM, 1962: 28-52), 11-27.

[7] I. H. Marshall, Kept by the Power of God (3rd ed.; Carlisle: Paternoster Press, 1995), 142, says: “The precise nature of the ‘heavenly gift’ is uncertain. It is unlikely that the Spirit is meant”.

[8] The proposal that the initial audience for Hebrews is the Hellenistic synagogues is further supported by the allusion to angels as the mediators of the old covenant (Heb 2:2). This notion, absent from Exodus 19-20, and alluded to in Deut 33:2, gained acceptance sometime prior to the first century and spread among Hellenistic Jews (cf. Acts 7:38, 53; Gal 3:19; Josephus Ant. 15.5.3). Note also that Hebrews 12 contrasts Jesus with Moses by alluding to Stephen’s (a Hellenistic Jew) defence in Acts 7: Moses whom they refused (Acts 7:35); who refused him that spake on earth (Heb 12:25); him shall ye hear (Acts 7:37); Him that speaketh from heaven (Heb 12:25); in their hearts turned back again into Egypt (Acts 7:39); if we turn away from him (Heb 12:25). The veneration of Moses in Hellenistic Judaism can be quickly determined by following up the indices in J. H. Charlesworth, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (2 vols; New York: Doubleday, 1983-1985).

[9] The typological details in Acts 19:13-17 are relevant to the judgment on Judaism anticipated by first century Christians. The house is a metaphor for the temple. The seven exorcists are an allusion to the priestly dynasty of the high priest Annas, who was also father-in-law to the high priest Caiaphas (Ant. 18.2.1, 2 and John 18:13), and who produced five sons who became high priest. Annas was the power behind the throne at Christ’s trial (Luke 3:2; Acts 4:6; John 18:24). See H. A. Whittaker, Studies in the Acts of the Apostles (Cannock: Biblia, 1985), 299-300, for an exegesis of the acted parable.

[10] Other noteworthy features in Matt 12:43-45 are the allusion to releasing the scapegoat (typifying the unclean nation sent into captivity) in the wilderness (dry places, cf. Lev 16:10) and the allusion to the feast of unleavened bread, when the Jews swept their houses clean of leaven in preparation for the Passover (Exod 13:7).

[11] Psalm 8 and 110 are also correlated by Paul in 1 Cor.15:27.