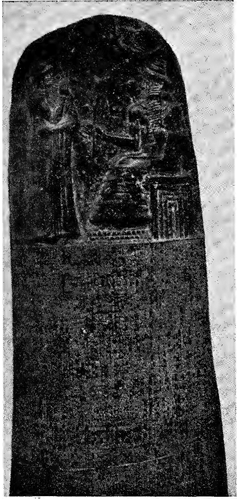

During the period December—January 1901-02, Mr. V. Scheil discovered at Susa, the Mesopotamia, a slab or stele, inscribed with Is a slab or stele inscribed with a law code. It is in the form of a boundary stone and stands about eight feet high. The upper rounded part of the monument tows Hammurabi, king of Babylon, receiving a sceptre and a ring from Shamash, the Babylonian sun-god, the god of justice. On the lower part of the stele is the code, the writing, which is in the cuneiform or wedge-shaped script, being from the top to the bottom. Seven columns have been deleted and it is suggested that these were removed to make room for the memorial of a much later monarch, who captured it.

The language of the code is Akkadian, the tongue which supplanted the earlier Sumerian in Mesopotamia. The names of Hammurabi’s parents were Semitic, but his is an Amorite one. In dress he compromised. His cloak and headdress were Sumerian, but he wore his hair long in Semitic fashion as the illustration shows.

Scriptural Interest

The find was a very valuable one from a Bible point of view. In the first place it shed light upon the rather obscure chapter, Genesis 14. Some 30 or 40 years previously, Professor Noldeke, an eminent Semitic scholar, had said that the chapter was unhistorical and his views were supported by Wellhausen, another well-known Bible critic. One expert even suggested was based upon the later invasion of Judah by the Assyrians under Sennecherib.

The Bible Record

Genesis, chapter 14, recounts that the kinglets of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboim and Bela, all from the neighourhood of the present Dead Sea, were subject to Chedorlaomer, king of Elam, for 12 years. At the end of that period they rebelled and a coalition of Amraphel, king of Shinar, Arioch, king of Ellasar, Tidal, king of nations and Chedor-laomer marched against them. The attacking armies advanced through the Euphrates valley, skirted the Syrian desert ; turned south near Damascus ; took the road on the east side of the Jordan valley, past the sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea, on to Mount Seir, overcoming various small Canaanitish tribes on their way. At Mount Seir, they turned west to Kadesh, and then north to the Vale of Siddim, where they encountered their foes. The king of Sodom and his allies were defeated and among the prisoners taken was Lot, Abraham’s nephew. Hearing of what had happened, Abraham armed his servants, went after the victors, attacked their rear ; released Lot ; and took a certain amount of spoil.

Critical objections to this acount were (1) that the implied supremacy of Elam over the other three of the four kings is unhistorical ; (2) that the overrunning of Palestine by troops from Mesopotamia at that early date was impossible ; and (3) that the names of the four kings were no more than political fancies.

These assertions have been roughly dealt with by archeological discoveries. Contemporary monuments show that Elam had become “supreme from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea and from the eastern borders of Persia to the Mediterranean”, the kings of Babylon and neighbourhood being subject to her. The name of Canaan an Babylonic was Amurru, or the land of the ;Amorites, and Kudur Nankhundi, king of Elam about 2,280 B.C. was called the “Father” or “Governor” of the land of the Amorites, a title which was stamped upon a brick of a later king of Elam, Kudur-Mabug, found at Ur of the Chaldees. These discoveries indicate not only that Elam was once the leading city-state in Babylonia, but that she had in fact over-run Palestine.

The Names Of The Kings

In 1871 the first of the names of the four kings was identified by Mr. George Smith, when he found the name of the son of Kudur Makug, Arioch, King of Ellasar. Next

The Stele Of Hammurabi

Hammurabi’s statutes, dated 2,100 B.C., were in force in Canaan from the days of the Patriarchs.

Amraphel, king of Shinar, or Babylon, was identified with the Hammurabi, king of Babylon, whose stele has already been described in this article. Tidal and Chedarlaomer remained. Dr. S. A. Cook stated in 1911, “The name Tidal, King of Goim (or nations) may be identical with Tudhula, mentioned in Babylonian inscriptions, and Goim may stand for Gutim, the Guti being a people who lived to the east of Kurdistan.” Dr. Cook further expressed the view, “Chedorlaomer, king of Elam, bears what is doubtless a genuine Elamite name.”

Chedor is the same as Kudur, which occurs in two names already cited, and means “servant”. Laomer was the Elamite deity Lagamar, and Chedor-laomer is therefore “the servant of Lagamar”. For some time, however, the name Kudur-Lagamar was not found on any monuments.

Eventually the late Dr. Pinches, of the British Museum, deciphered writings which came to be known as the Spartoli tablets. These describe how Babylonia was laid waste by certain kings. The names of three of these kings were readable. They were Tudkhula, Eri-ahu and Kudur-Lagumal, who was described as “King of Elam”. Thus three of the names of the four kings referred to in Genesis 14 were found in one place. Dr. Pinches was a very modest man and his modesty and caution are reflected in his comment on his find : “It is in the highest degree unlikely that tablets containing the names of Tidal and others closely resembling Arioch and Chedorlaomer, the last being designated “King of Elam” and “the Elamite”, should not, after all, refer to these personages.” Dr. Pinches can hardly be accused of over-statement, rather the reverse. Moreover, Mr. T. Miller Neathby’s tribute to the Genesis writer is fully justified :

“Writing at least four or five centuries after the event, he mentioned names so remote from the general knowledge that their very genuineness was boldly denied and could not indeed be confirmed until the only other fountain of information was opened up ; that is, the monuments of archaeology. Clearly this writer was not drawing upon a fleeting tradition of knowledge general in his time, but was tapping some genuine but not general source of history. If that were so, it is a fair inference that he was able to supply much more than mere names. As a matter of fact, he supplied not merely the names of certain great historical figures, but a definite and (again) unexpected and (until recently) much disputed political background to their exploits : and both have been confirmed by the monuments.”

The route which the four kings followed has already been described in some detail, following the Genesis narrative. This record in time past received almost as much ridicule as the names of the kings. Peake wrote, “Assuming that the object of the campaign was to crush the rebellion of the five kings, its course as described from verse 5 and verse 8 is very curious”. The reply to this and other more drastic suggestions of the unhistorical character of the chapter is given by Dr. Albright, the well-known American archaeologist, a man who changed his mind. He wrote,

“Formerly the writer considered this extraordinary line of march as being the best proof of the essentially legendary character of the narrative. In 1929, however, he discovered a line of Early and Middle Bronze age mounds, some of great size, along the route of the kings’ march down the eastern side of the Jordan and especially at places mentioned in the Genesis record, Astoreth ,Karnaim and Ham.” As Mr. Miller Neatby says, “This means that he (Albright) found, dating to between 2,500 and 1,600 13.C.—within which period fall the times of Abraham and the Eastern kings—centres of population and culture, long since dead (save in the Book of Genesis) where lived the Zuzims, the Emims and the Rephaims”.

The Law Of Moses

The discovery of the stele of Hammu-rabi was valuable in another way. Previously critics had affirmed that the Law of Moses could not have been given by Moses, because there was no people in the world who were sufficiently advanced for such a Law at the time at which he lived. Hammurabi’s Laws, however, dated to about the time of Abraham, hundreds of years before Moses, and this fact, among others, compelled the abandonment of the critical theory.

Abraham And Babylonian Law

A comparison of the legal dealings referred to in the Book of Genesis with Hammurabi’s laws is very informative. In this connection attention is drawn to the difference in Abraham’s conduct on the occasions of the two departures of Hagar from his encampment. On the first occasion Sarah was barren and had given Hagar as a concubine to Abraham, so that he might have an heir. Realising that she was to have a child, Hagar derided her childless mistress. Sarah complained to Abraham and he replied, “Thy maid is in thine hand, do to her that which is good in thine eyes.” Thereupon Sarah made Hagar’s life so hard that she ran away and had to be persuaded to return by an angel. Later, Ishmael was born and became Abraham’s heir. Later still Sarah herself bore Isaac. At Isaac’s weaning feast, Hagar was discovered mocking, perhaps because of her disappointment at the loss of

her son’s prospects. Sarah was incensed and demanded of her husband, “Cast out this bondwoman and her son ; for the son of the bondwoman shall not be heir with my son, even with Isaac.” This time, however, Abraham was displeased with his wife’s antagonism toward Hagar and did not desire to grant her wish. God, however, intervened and at His behest Abraham sent Hagar and Ishmael away into the wilderness, out of his house for ever.

On the face of it, it seems likely that, on the first occasion Abraham, not having an heir, would have been anxious to keep Hagar in the camp, rather than subject her and her unborn child to the hazards of the wilderness. On the second occasion. Isaac had been born and Hagar’s well-being was not so important to him. Why then did he agree to send her away on the first occasion and was so reluctant to do so on the second ?

The apparent inconsistency is explained by an understanding of Hammurabi’s law, with which Abraham was familiar. Under this law, a man could not in principle possess more than one legitimate wife. If, however, his wife was barren he could either divorce her or take another wife of secondary rank. Concerning the secondary wife or concubine, it was decreed he shall “bring her into his

house”, but this concubine shall not make herself equal with his wife.” The legitimate wife could, however, deal with the situation in her own way, as Sarah did, by choosing a maid from her own slaves and giving her to her husband as a concubine. If and when the slave-woman’s son was born, he became the lawful heir and the father was no longer entitled to introduce another woman into

the house. “If she has given a bond-maid to her husband and she has borne children, if he plan to take a concubine, they shall not give that citizen permission, a concubine he may not take.” The real wife still had her rights. The concubine was not permitted to become her rival. If she attempted this, the wife could sell her, if no child had been born ; if a child had been born she could reduce the concubine to slavery.

“This is just what happened in the case of Hagar’s first departure. The Egyptian woman had attempted to “make herself equal” with her mistress, and, guided by the law, Abraham felt that he had no alternative but to leave the matter in Sarah’s hands. “Do to her that which is good in thine eyes”.

On the second occasion the situation was different. Sarah’s demand was that Ishmael should be disinherited. This was completely contrary to the law which Abraham knew. Disinheritance could not be carried out at the whim of the property owner. It had to be performed legally and for good reason.

“The judge shall enquire into his reasons and if the son has not committed a heavy crime which cuts off from sonship, the father shall not cut off his son from sonship.” Apart from this general enactment, the position of both Hagar and Ishmael was legally secured. Concerning the offspring of a concubine it was provided, “If a man whose wife has borne him children and (also) his bondsmaid has borne him children (and) the father during his lifetime has said to the handmaid’s children, which she has borne him, “My children” : he has added them to the children of the wife. After the father goes to his fate, the children of the wife shall divide the property of the father’s house equally with sons of the bondmaid.”

Hagar seems to have been protected by this provision, “If a man has set his face to put away his concubine who has borne him children . . . to that woman he shall return her marriage portion and shall give her the fruit of field, garden and goods and she shall bring up her children.”

Thus in both incidents, Abraham was striving to keep the law and was prepared to grant his wife’s second request only at the overriding behest of God, Who recognised the grounds of the patriarch’s concern at her demand by revealing that He would compensate Ishmael for the loss of his heritage. “Let it not be grievous in thy sight because of the law and because of thy bondwoman ; in 101 that Sarah bath said unto thee hearken unto her voice ; for in Isaac shall thy seed be called. And also of the son of the bondwoman will I make a nation because he is thy seed.” The consistency of Abraham’s would-be conduct is clearly seen in these comparisons of Scripture and monuments.

After Sarah’s death, Abraham married Keturah, and by her he had six further children. When these came to maturity there were no complications as in the case of Isaac and Ishmael. We are told, “Abraham gave all that he had unto Isaac. But unto the sons of the concubines which Abraham had, Abraham gave gifts and sent them away from Isaac his son, while he yet lived, eastward into the east country.” This procedure was clearly in accordance with Hammurabi’s law. Children remaining under the parental roof until the father died shared the estate according to fixed rules. A father could, however, during his lifetime make over part of his belongings to any of his sons or could will it to him. After his decease a son so benefiting could take out his special portion first and then receive his legal share of what remained. By agreement with the father, moreover, a son could receive his portion of the inheritance in advance and could leave home, renouncing any further claim on the estate. This legal provision was followed by Abraham in the case of the sons of the concubines, and the parable of the prodigal son, spoken by Jesus, is also based upon it. By it also we are able to understand how Isaac became Abraham’s soleheir.

Machpelah

When Abraham purchased Sarah’s burying place at Machpelah, he weighed out the purchase price in silver. This was not in the form of coin, backed by Government guarantee, but was the actual amount of silver due. The law also required that tablets signed and witnessed by both buyer and seller should be exchanged in property transactions and doubtless both Ephron the Hittite and the Patriarch followed the practice when the cave changed hands. It is also likely that Abraham’s steward carried tablets to establish his credentials when he went to Mesopotamia to seek a wife for Isaac.

Dr. Woolley

Writing on the correspondence between Genesis and Babylonian law, Dr. Woolley

wrote,

“As it is, they (the Genesis records) are unobtrusive, and they reflect accurately the conditions peculiar to the period with which the stories deal, and therefore they have the greatest weight as evidence for the date of the stories. From the faithfulness of local colour which a later age could not have produced, we can argue the antiquity of the oral tradition. This does not in itself prove that the stories are true . but where the account is not intrinsically improbable, only prejudice will reject it.”

This comment is restrained, and we might think that Dr. Woolley could, without risk of error, have been more positive, but it will serve as an epilogue to our consideration of Hammurabi and his laws.