Introduction

Genesis 6-9 describes the flood with comparatively little physical detail. The global flood interpretation has substantial opposition from many scientific disciplines; the local flood reading has considerably less (if any) problems. The Mesopotamian region is known for extensive flooding throughout the ages.[1] Nevertheless, there is some physical detail that we can examine and thereby evaluate whether the flood account is a reasonable description of a catastrophic local flood in Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia

Pollock notes that “Mesopotamia is, geologically speaking, a trough created as the Arabian shield has pushed up against the Asiatic landmass, raising the Zagros Mountains and depressing the land to the southwest of them. Within this trench the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers and their tributaries have laid down enormous quantities of alluvial sediments, forming the Lower Mesopotamian Plain…Today the Lower Mesopotamian Plain stretches 700 kilometers…to the west of the Euphrates, a low escarpment marks the southwestern boundary of the alluvial plain and the beginning of the Western Desert”.[2] The Mesopotamian Basin can be divided into the Upper Plain above Baghdad, the River Plain below Baghdad and the Delta Plain in the south.[3]

This description of an extensive flood plain satisfies one of the conditions of the physical description of the flood, viz. that it extended beyond the visual horizon of Noah “under the whole heavens”. If we place Noah in the south, on the Delta Plain, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, where the Gilgamesh Epic places Utnapishtim,[4] then the “high hills” (Gen 7:19, KJV) on the plain would have been covered “under the whole heaven” from Noah’s vantage point. As the waters prevailed upon the land by overflowing the river channels of the Tigris and Euphrates and their tributaries in the south, the high hills on the surrounding plain would have been covered. The Hebrew for “hills” is the same as for “mountains” (Gen 7:20), but the use of “mountains” in English versions gives an impression of global proportions for the flood. This fails to take into account the question of perspective implied by “high” in relation to a plain. The Hebrew word involved can be equally “hill” or “mountain”.

The Hebrew for “high hills” is ~yhbgh ~yrhh, and this expression is necessarily of relative perspective. A “high hill” to a dweller on a flood plain is not a high hill to a dweller in the Zagros Mountains. Within the alluvial floodplain there would have undulating hills of low proportions (sand hills, sedimentary deposits, old levees,[5] low ridges[6] and abandoned city-mounds for the flood waters to overflow. The “high hills” would not denote the Zagros Mountains or the foothills of these mountains. They are the hills local to the ark’s point of departure in the south of the Mesopotamian flood plain.

The waters “prevailed” upon the land; they increased gradually and lifted up the ark above the ground (Gen 7:17). The depth of the waters is given as 15 cubits above the high hills,[7] a measure which is a significant indicator of the local proportions of the flood. This sort of measure would be taken by soundings and such a short measure only makes sense in a local situation.[8] Alternatively, the measure might have been determined from the draught of the ark. More importantly, this measure is taken at the point where the ark becomes buoyant.[9] This measure should not be applied by a reader elsewhere in the Mesopotamian Basin, where the river channel, the associated floodplain, and the local topography would have produced different measures. Thus, water may have been deep around the river channel but less so at further distances in other areas. In the south, where the flood plain of the Tigris and the Euphrates is extensively flat, the depth of the flood need only be shallow by this measure. Thus, for example, a 40 foot undulation would require a 70 foot flood depth.

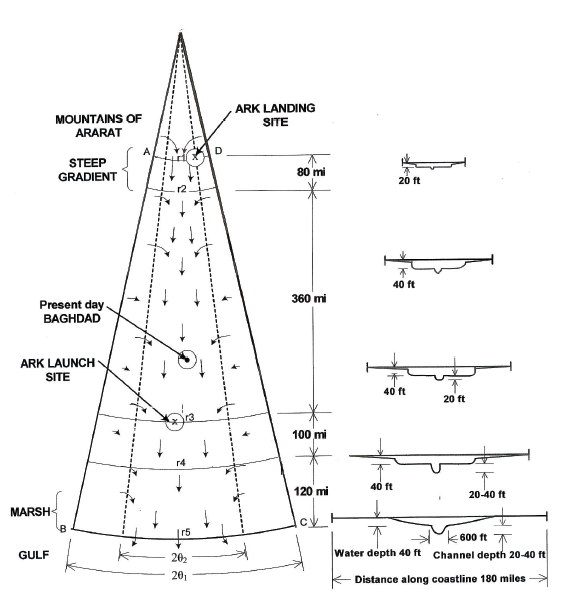

E. Hill has proposed a geometric model for the flood. He includes a diagram (Diagram 1)[10] which offers a proposal on how extensive the flood could have been progressing up the Mesopotamian Basin and how varied the flood depth could have been extending out from the river channels. He locates the ark launch point at Shuruppak in the south a city on the Euphrates, following the Gilgamesh Epic. The Bible account does not locate Noah, but such a location would fit the flood account, and in this case the high hills such as levees and city mounds nearest the river are those that would be the ones covered. Hill locates the resting place of the ark in the north near Cizre, which has substantial traditional support, however, the Bible does not state where in the region of Ararat the ark rested.

Ararat

The ark landed “upon the mountains of Ararat” (Gen 8:4, KJV). Ararat is a region that extends south into northern Iraq (2 Kgs 19:37; Jer 51:27),[11] but the account does not indicate where in Ararat the ark grounded. No inference can be drawn from the word translated “mountains” as to the depth or extent of the flood in Ararat. The account implies that the flood was extensive in the south where the ark was launched, but there is no statement of extent for the resting place of the ark. Further, as already noted, “mountains” in Hebrew could mean “hills”. The geographical perspective of the text could well mean the foothills of Ararat that set the boundary of the Upper Plain. The flood waters beyond the Upper Plain could therefore have been narrowly confined and the ark could have travelled within the deeper water of a river channel and come to rest upon the banks of the Tigris besides the foothills of Ararat. The Hebrew preposition translated “upon” in the KJV and other versions has a wide variety of senses including a locative sense of “besides, by” (e.g. Gen 14:6; 16:7; 29:2; Num 3:26; Job 30:4).[12]

Diagram 1

Water

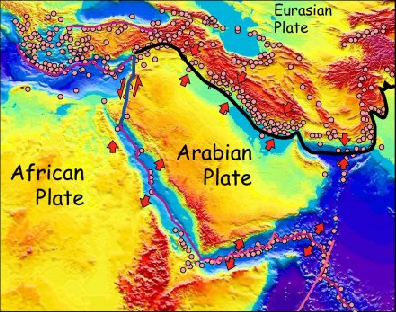

A local flood satisfying the measure of 15 cubits above the high hills requires a great deal of water in the south. Two sources are stated: rainfall and the “fountains of the deep” (Gen 7:11). This expression “fountains of the deep” has been taken to denote subterranean water but it is more likely to indicate tidal wave inundation from the Gulf. The Arabian Plate is subtended under the Asian plate along the western side of the Gulf (See Illustration 1) and any underwater volcanic activity (or quakes) could have led to tidal wave surges to extend inland over the Delta Plain for a considerable distance. With rainfall swelling the river system in the north and overflowing river channels in Upper Plain and the River Plain in all directions as it moved south, incoming tidal water (with eroded deposits off the Delta) would have seriously impeded water flow to the Gulf by creating widespread dams. This would have slowed the assuaging of the waters, thereby adding to the depth of the flood waters and their extent in the south on the Delta Plain. The whole delta lowland south of Baghdad is extremely flat and rises only a few metres from the Persian Gulf to Baghdad, so that Baghdad is still less than 10 metres above sea level; in effect the flood would have extended the Gulf.

Weather systems that could give rise to extended rainfall are known for the region. Exceptional cyclonic rain,[13] coinciding with spring snow melt in the mountains that feed the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, along with geologic disturbance at the boundary of the Arabian Plate creating tidal waves, can account for the flood.[14] The resulting flood would have been most extensive in the Delta Plain but less so in the Middle River Plain and the Upper Plain.

The scale of the flood on a local reading is large, as is the volume of water. But there is nothing in the biblical account itself that is implausible for the region in terms of these hypothetical weather conditions or the inundation of the sea that would exclude the explanation of a local flood for Genesis 6-9.

Illustration 1

The size and construction of the ark is that of an exceptionally large river barge, assuming a standard Israelite measure for the cubit. The stresses that the ark could bear and the water seepage that the ark would bear preclude a violent global flood. We do not know the number of animals or the volume of food in the ark; all we can do is guess at relatively small numbers and volumes given the implicit land husbandry of the “clean” and “unclean” directions.

As floods leave deposits and erode material, and the Mesopotamian Basin has always been subject to flooding, the physical evidence for Noah’s flood will have been affected in subsequent smaller floods, changes in sea level, and the shifting course of the rivers. Archaeological digs have found flood deposits in levels for various Delta Plain cities around 2900 BCE, and some have postulated that this may be evidence of Noah’s flood. Others have argued that 3500 BCE is a likely date and have pointed to other flood deposits as evidence.[15]

The End of the Flood

Having stated that the waters prevailed for 150 days (Gen 7:24), the account next describes the fortieth day of the flood and why the waters prevailed for 150 days (Gen 8:1-4). This can be inferred because Gen 8:3 mentions the end of the 150 days. The explanation given is that although on Day 40 the rain was restrained, and the windows of heaven[16] and the fountains of the deep were stopped, the waters prevailed for 150 days because the waters receded slowly. The Hebrew uses the verb “to go/to walk” in the infinitive (Gen 8:3) to describe the recession, so that we can say, the waters receded walking. During this period of 150 days the ark travelled to Ararat. For this to have occurred against the flow of water downstream, wind would have to have driven the ark north up the river channels.[17] It is perhaps noteworthy in this connection that the account mentions a wind as the mechanism whereby the waters were assuaged (Gen 8:1), however, such a wind would have been opposite to that required to push the ark north. A southerly wind is necessary to move the ark; the journey may have been long or short during the 150 days.

In Gen 8:5, a time period of 73 days is implied after the 150 days in which waters continued to decrease after which the tops of the hills that had been covered (Gen 7:19) were seen. The text here is not saying that they were seen by Noah; rather, this is a narrator’s statement that the hills that had been covered in the Delta Plain were now revealed. At this point in the story, Noah is hundreds of miles to the north of his former homeland.

The narrative has symmetry in its second mention of 40 days. As the catastrophe draws to a close, a period of 40 days sees Noah wait before sending out a raven and a dove. Noah sends out a raven and then a dove or, more likely, a homing dove (Gen 8:9).[18] A homing dove would be trained to return to home (in this case the ark).

On the first flight, the dove returned almost immediately unable to find rest for its foot in the vicinity of the ark. On the second flight it was able to stay out all day, until evening, and bring back a plucked olive leaf. The mention of the “plucking” of an olive leaf indicates fresh growth and this is another indicator that the flood was local to the Mesopotamia Basin. The dove would have had to have found olive trees on well-drained low ground unaffected by the flood, as olive trees would not have sprouted fresh growth under water for the year of the flood. Noah’s inference from the freshly plucked olive leaf that the waters had abated rests upon his knowledge that the dove needed rest during all day flight, rather than any presumption that flood waters had receded to reveal freshly sprouting trees.

After the waters had abated, Noah and the animals disembarked to a devastated landscape unable to support life. The land would need to spring back to life; Noah would need to re-introduce animal husbandry and arable farming. The non-domestic animals that were not going to be kept by Noah would migrate to the areas unaffected by the flood. Noah himself would migrate to such a region. In time, the devastated land would be replenished.

Conclusion

In this article, we have offered a physical description of the flood based on the text. The key ideas have been i) identifying the source of the water; ii) explaining the slow recession of the water through tidal wave deposits; iii) allowing for extensive flooding in the south and less extensive flooding in the north; iv) postulating a river barge driven by a wind northwards against the flow of water and following the river channels; and v) explaining the olive leaf as vegetation from an unaffected area.

Postscript (Andrew Perry)

There are many websites arguing for a local flood and a global flood. This series of articles has presented the case for a local flood. It lies outside the remit of the EJournal to argue the scientific aspects of either view. In respect of a local flood, the scientific argument revolves around i) whether an ark of the stated size could have been constructed at that time and been weather-proof; ii) whether the loaded weight of the ark and its draught in the water is realistic; iii) whether the wind velocities necessary to drive the ark north against the direction of water flow are feasible; iv) whether the rate of water flow and recession of the flood towards the open Gulf makes a Mesopotamian flood implausible; and v) whether erosion can account for any absence of flood deposits today. The relevant scientific disciplines here are marine engineering, hydrology, climatology and geomorphology.

Biblical interpretation can only interpret the text and make sure that possibilities are clearly stated. Thus the text cannot settle the question of whether an ark of the stated dimensions could have been constructed at that time. The text allows for any construction to be proposed by a marine engineer that satisfies the contextual requirement of a very large river barge. In terms of the weight and draught of the ark, the key variable of the number of animals is unknown and the text’s stipulation of “clean” and “unclean” suggests a small number. Likewise, the depth of the main river channels is unknown and how far they were navigable. The depth of the flood was relatively shallow by the one measure given, but also unknown. The Delta Plain is extensive and the speed of water flow and drainage would have been affected by the high water table, marshland vegetation, and the extent of the water. Tidal wave inundation and any tidal deposits would affect water flow to the Gulf. Similarly, sedimentary deposits from the riverine flood waters would have affected flow. Rises in sea level are also possible. These factors are the variables which affect the judgment as to whether the “open end” of the Mesopotamian Basin would have allowed the flood waters to decrease slowly as the text requires.

These are the sort of scientific issues that arise in discussion of the theory of a local Mesopotamian “Noah’s flood”. This remains the most common “local” reading because the biblical account bears many similarities to Mesopotamian flood accounts.[19]

Biblical objections to a local flood arise from i) the question as to why an ark was built: why was Noah not told to simply migrate away from the flood area; ii) the question of whether the account allows for there to be human and animal life unaffected by the flood outside Mesopotamia; and iii) the question of whether a local flood in Mesopotamia could have achieved the objective of destroying life even in that region.

As with any differing interpretations, dialogue proceeds via proposal, objection, revised proposal, counter-objection, and so on. So it is with the local reading of Genesis 6-9. Thus the choice of salvation through an ark is just that—it is a choice that resonates with Genesis 1 and serves as a typology of salvation in a way not possible in a story of “migration to another land”. As for the possible existence of human and animal life outside Mesopotamia, the local scope of the flood is shown in the genealogy of Genesis 10; the peoples that come from Noah’s sons migrate from Mesopotamia. The “rest of the world” is an unknown quantity in biblical terms. Would a local flood have destroyed life even in the Mesopotamian Basin? This question depends on how violent we imagine any tidal-wave inundation in the Delta Plain, but what is known from recent times of the rapid and destructive power of tidal waves makes the “fountains of the deep” coupled with cyclonic rain a plausible force for a total destruction of the Delta Plain.

[1] L. R. Bailey, Noah: The Person and the Story in History and Tradition (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989), ch. 2.

[2] S. Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 29. Pollock’s chapter 2 should be consulted for the geography of Mesopotamia in ancient times.

[3] Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia, 30.

[4] Our text is taken from the convenient edition of A. Heidel, The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels (2nd Ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1949) and the reference is XI.11-14.

[5] Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia, 33.

[6] Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia, 29.

[7] The Hebrew and the LXX allows the 15 cubits’ measure to be above the land rather than the high hills, and if this were the case, the high hills would be river embankments.

[8] C. A. Hill, “The Noachian Flood: Universal or Local”, Perspectives on Science and the Christian Faith 54/3 (2002): 170-183 (174).

[9] A. E. Hill, “Quantitative Hydrology of Noah’s Flood”, in Perspectives on Science and the Christian Faith 58/2 (2006): 130-141 (130).

[10] “Quantitative Hydrology of Noah’s Flood”, 132.

[11] Bailey discusses the shifting extent of the region of Ararat down the centuries, Noah: The Person and the Story in History and Tradition, 55-61.

[12] See BDB 755, note 6, for more examples.

[13] The Mesopotamian flood accounts mention “wind-storms” and “south-storms”, see J. B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 44, 94.

[14] C. A. Hill, “Qualitative Hydrology of Noah’s Flood” Perspectives on Science and the Christian Faith 54/3 (2006): 120-129 discusses the weather requirements.

[15] Bailey, Noah, ch. 3, sets out the evidence.

[16] The “windows of heaven” may be a figure for violent rainfall thus allowing more restrained rainfall to have continued during the 150 days.

[17] Hill, “Quantitative Hydrology of Noah’s Flood”, 137-139, offers an estimate needed for the speed of the wind. The variables are the weight of the ark, the gradient, and the flow of the water downstream. He offers 4 possible cases, the “lightest” of which would be for a wind of between 54 mph and 70 mph.

[18] The Hebrew term is translated as both “dove” and “pigeon” in the KJV. E. Firmage in his article “Zoology” in Anchor Bible Dictionary (6 vols; ed., D. N. Freedman; New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6:1145, treats doves and pigeons together but states that homing pigeons are not attested for Mesopotamia so far. The story of Noah could be the only evidence of homing birds for Mesopotamia.

[19] Hence, proposals of a flood in the Mediterranean Basin, the Black Sea Basin and the Caspian Sea Basin have garnered little support.